As an invention that predates our modern understanding of sound waves and the notation and tuning systems in use today, the pipe organ is impressive to say the least. Get a church organist to hit the right combination of keys and those stories of creation and apocalypse will need no further explanation, as air shuddering through the towering metal flues and finely honed reeds summons up a chorus of a hundred angelic trumpets or the groans of the eternally damned.

Today, however, most of us prefer our revelations to come coded at 192 kbps, whispered divinely into our ear canals as we go about our business in a world whose everyday activities would have a medieval organ-builder whimpering and gibbering about witchcraft. But if you could pop a pair of headphones on him before he turned on his heel and fled, that distant ancestor of Bob Moog might find something familiar in much of today’s ambient and drone music: namely, the shifting, complex textures, the slow, hypnotic pulses and the love of a good fire-and-brimstone climax.

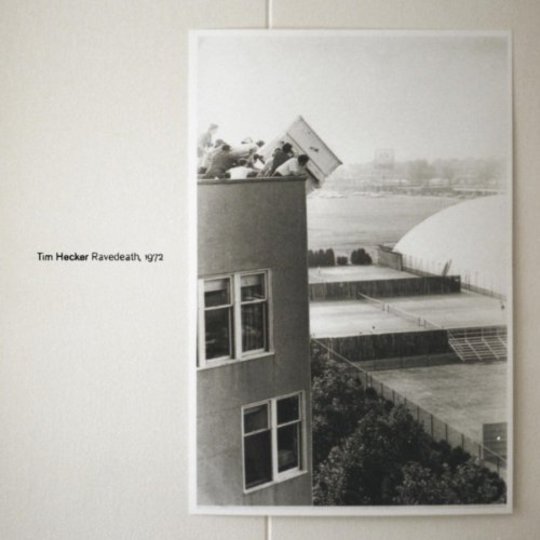

Montreal-based sonic architect Tim Hecker must understand this, having drawn much of the sounds from which Ravedeath, 1972 is composed from a session with an old pipe organ, recorded, along with guitar and piano in an Icelandic church, with fellow musician Ben Frost helping out with performance and engineering. The initially cryptic title makes more sense when considered as a wry, triangular pun whose other corners are the opening track, ‘The Piano Drop’, and the cover image, a photo of Hecker’s wall bearing a copy of a black and white picture of a group of American students in 1972 on the verge of executing a ritual ‘piano drop’ off the edge of a tall building. The track itself is the nearest you’ll find to anything resembling dance music here and that’s only in the way its stacked tremolo fuzz and floor-dwelling bass suggest a smudged, bleached-out photocopy of some near-forgotten trance anthem.

Bearing equally mysterious titles – ‘Analog Paralysis 1978’, ‘Hatred of Music’ parts I and II – the album’s other tracks invite similar speculation. But too often writing about drone music comes off as an attempt to use words to justify its grandiose buttresses and gravity-defying domes from the ground up, as though a sound whose richness offers so much to the imagination but does little to direct it needs an intellectual scaffold for support. So whatever grand plan Hecker may or may not have had in mind here, let’s just say that much of Ravedeath, 1972 will put you in the position of a slack-jawed medieval peasant, floored by hearing the power and beauty of that organ for the first time.

Had John Martyn not got there first, the album could easily have been titled Solid Air, as Hecker’s layering of multiple ambiances, effects and sonic manipulations sculpts a series of colossi out of echoes, fleeting impressions and the split seconds either side of something happening. The three-part ‘In The Fog’ sees glinting, Terry Riley-esque organ tones and piano chords that drop like melting icicles battling successive waves of hiss and distortion and corroded, rust-edged guitar. ‘No Drums’ provides a murky, underwater interlude whose initially optimistic strain of melody repeats to the point of stifling claustrophobia, before ‘Hatred Of Music’ spills forth. Here, the music shudders and churns before collapsing inwards under its own mass in a way that recalls the dark ambient spacescapes of Tangerine Dream’s Zeit, one artefact from 1972 that still sounds detached from its era.

Yet despite song titles such as the above and ‘Studio Suicide 1980’ – the latter offering a faint glow of melodic sunlight through thick, murky stained glass – the dominant flavour of Ravedeath, 1972 isn’t one of decay. It draws upon the grandeur of the past but refuses to crumble its bones into sonic dust, instead recasting the organ’s strength and harmonic range into shapes more suited to an age when an imminent day of judgement is feared less than the constant trickling away of the present. As the final minutes of three-part closer ‘In The Air’ sees slabs of astringent white noise give way to contemplative piano, Hecker even teases us with snatches of what could be human singing, but might just be another organ sound. The voice of God, indeed.

-

9Abi Bliss's Score

-

8User Score