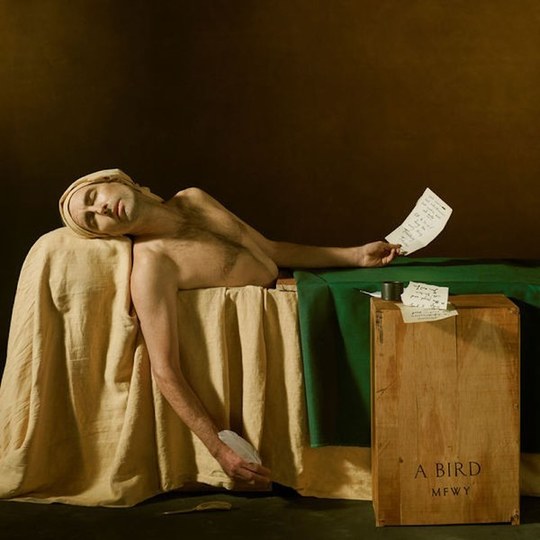

Indie auteur Andrew Bird, in his major releases, has recently made a transition from the abstruse art-pop of his early career to more earthy, nearly traditional singer-songwriter fare. While maintaining his distinct sound and presence, he seems to be growing less guarded and remote. The days of his long retreats to that western Illinois farmhouse are over. His last album, Are You Serious, was hailed as his first ‘vulnerable’ release because of its relatively direct, occasionally autobiographical lyrics and more standard pop structures. My Finest Work Yet is being called Bird’s first ‘political’ album, and pushes the composer further into the realm of accessibility. It’s a piece of masterful craftsmanship tucked snugly into the singer-songwriter tradition, filled with country-soul ballads and grungy laments driven by jangly guitars, family band harmonies, rumbling pianos and cinematic string passages that should appeal broadly to fans of the genre without alienating his own die-hards.

His calling cards are here — the virtuosic whistling, erudite references to mythology, literature and history, richly orchestrated violin loops, meticulous detail – but it’s all used with a lighter hand. Like Sufjan Stevens, who on Carrie & Lowell seemed so at ease melding the disparate styles he had traversed up to that point in his career, Bird comes across on this record as being much more comfortable with himself, more discerning with his skillset. His lyrics convey a similar confidence, no longer cloaking sentiment and thought in elaborate ambiguity. It’s a tone that reinforces the overriding message of the album, that open communication, especially with our nemeses, is perhaps the best antidote to the political and cultural tribalism unseaming society. “Our enemies are what make us whole… This ain’t no remote atoll”, he sings on ‘Archipelago’, the album’s thematic center of gravity, echoing John Donne’s famous meditation on humankind’s collective fate: ‘No man is an island entire of itself’.

Despite this often weighty content, the narrative tone and music itself usually belie the breathless anxiety that motivates most discussions on topics like digital isolation or mass media manipulation. The album is mostly acoustic, and was largely recorded live, everyone bleeding into each other’s mics. This technique, inspired by Bird’s favorite Fifties/Sixties jazz recordings, adds to the organic sonority of the instrumentation and the sense that the musical language, at times as suggestive of Maurice Ravel as Bill Withers or Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, is meant to expand our perspective on these contemporary worries, to both indict complacency and temper sensationalism by evoking other troubled times, other bewildered voices. His verses are often similarly circumspect, considering the myths of ‘Sisyphus’ and ‘Manifest’ Destiny and human exceptionalism alongside the 2008 housing bubble, post-truth fatalism, and environmental apocalypse, or coolly drawing a comparison between the lead-up to the Spanish Civil War and the venomous divisions in contemporary western politics on ‘Bloodless’.

That same Donne meditation was used by Ernest Hemingway to title his novel on the same war, For Whom the Bell Tolls. For whom? ‘For thee’, replies Donne, each death knell for anyone equally a sign of our own mortality. Hemingway’s work, too, ponders how a community can be fractured by populists in search of power and profit, and became prophetic when the gruesome regional conflict in which it’s set ended up a prelude to the incomprehensible global carnage of WW2. The personal authenticity Bird suggests as a safeguard against these potentially explosive rifts now takes on added urgency. “You just have to look into my eyes… To know how this song is sung/ And that what I say is true”, he prays on ‘Cracking Codes’, probably the most plainly beautiful of these ten tunes, filled with the mourning of someone at their wits end, grasping to save a relationship on the brink. Yet he’s too wise to be sure of success. “Are we smarter alone or in this endless Stockholm syndrome?”, he asks on closer ‘Bellevue Bridge Club’: “Here's what is known/ We're gonna break this two-way mirror”. With this doubt Bird finishes My Finest Work Yet honestly and without losing conviction or courage, fittingly leaving things open to further debate.

-

8Joey Rabchuk's Score