Shahabuddin Muhammad Shah Jahan, the fifth Mughal Emperor, reigned India between 1628 and 1658. Held among the greatest leaders of all time, he presided over ‘the Golden Age of the Mughals’. Despite this, exploits on multiple fronts – wars against the ancient provinces of Balkh and Badakhshan and attempts to regain the city of Kandahar from the Safavid dynasty – saw him lead his empire to the brink of bankruptcy.

Kanye West’s multiple fronts of activity include fashion designer, label boss, celebrity troll, greatest living rock star on the planet, 2020 US presidential candidate and (as of last week) computer game designer. If reports, and his own latterly hyperactive Twitter feed, are to be believed, Kanye is also experiencing some $53million of financial difficulty right now.

Of all his achievements and failures, in the early twenty-first century Shah Jahan is best remembered for one thing. He is the man who created the Taj Mahal, a palace of such beauty has been it has remained feted and fabled down the centuries. All the noise surrounding Kanye West’s travails in various fields can tend to obscure the one thing he is certain to be remembered for. He is, in case you hadn’t heard, a musician and producer responsible for some of the most exceptional popular music of our era.

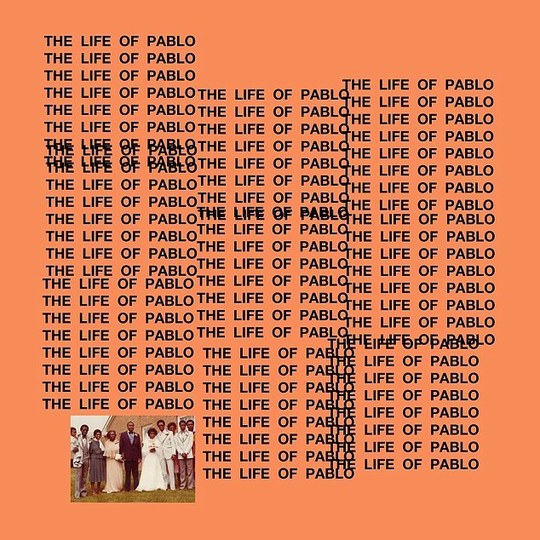

If it may sound hubristic to compare a rapper to an emperor, it is only to discuss Kanye on his own terms. The man who calls himself Yeezus has never been slow at self-worship. Our political leaders may no longer present themselves as gods, but our rappers do. The Life of Pablo proves that sometimes they give us our Taj Mahals too.

The record – if it can be called a record; it is currently only available as a stream – opens with a track of near divine beauty. ‘Ultra Light Beam’ fits the poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore's description of the Taj Mahal – ‘a teardrop glistening spotlessly bright on the cheek of time’ – as well as any song I can think of. Unexpectedly for Kanye, it’s a work of inexorable subtlety. Minimal drums patterns appear whole stanzas apart, what sounds like reversed organs suck like gentle breaths, stabs of brass are conjured from air then disperse like smoke, downtuned vocals burble before a choir of voices building to a surging crescendo. “This is a god dream, this is a god dream” sings Kanye, amid gospel-tinged verses from Kelly Price and Kirk Franklin. The whole thing is flayed across an intense rap from Chance the Rapper. There are other mighty moments on this record, but none top this extraordinary opener.

‘Father Stretch My Hands, Pt 1’ flips from wholesale plunderphonic sampling of some classic Chicago soul to Hi-NRG R&B with a typically bravado disregard for time signature. After the holy opener, Kanye hammers the listener back into the corporeal world. The opening rap is flat out ridiculous: “Now if I fuck this model/And she just bleached her asshole/And I get bleach on my t-shirt/I’mma feel like an asshole”. It’s the same juxtaposition of the divine and the earthly, the ego and uncertainty, that made Yeezus such a complex character. Elsewhere we find a much more relaxed Kanye than on this recording’s immediate predecessor. Vocally, Kanye is less prone to dominate the songs.

Late addition ‘30 Years’, strapped to an ethereal Arthur Russell loop, has a vocal taped - in part at least - after that mad Madison Square Gardens playback party. In its casual recollection of events from his life, it recalls ‘Last Call’, the epic freestyled closer to his debut LP, The College Dropout. Kanye has rarely allowed himself to sound so casual on record since.

On ‘No More Parties in LA’, layers of production drop out after Kendrick Lamar’s superlative verse to allow a fresh voice to spring into the hook. It’s an old, if incredibly effective, Kanye trick, one that he used to reserve for appearances from Jay-Z (see the ‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’ remix for the master class). Nowadays it’s Kanye’s own vocal that is afforded the treatment. Far more subtly than he could manage in a tweet, he declares to the upstarts that surround him exactly who the ‘OG’ is around here now.

Not that his position in his self-made world is in doubt. “I made Kanye” he raps on 44 second a cappella ‘I Love Kanye’, a kind of bizarre solo meta skit. On ‘Ultra Light Beam’, Chance drops the line “I made ‘Sunday Candy’ I’m never going to hell” bowing to Kanye’s “I made ‘Jesus Walks’ I’m never going to hell” line from ‘Otis’. He follows with: “I met Kanye West I’m never going to fail” bowing yet deeper. Even imprisoned rapper Max B – whose alleged ownership of the term ‘wavy’ led to the Wiz Khalifa spat and that 'I am your OG' tweet – phones in to pay tribute.

If the ego-stroking is incessant, tracks like ‘Famous’ and ‘Waves’ at least remind us why tribute is due. The former, already notorious for the line about Taylor Swift, is a magnificent piece of production, wrapping Rhianna’s rereading of Nina Simone’s Do What You Gotta Do into a sample of Sister Nancy’s iconic dancehall track ‘Bam Bam’ before an outro of Nina Simone’s original vocal. It’s a song dominated by strong female voices that undercut Kanye and Swizz Beats’ braggadocio. ‘FML’ and ‘Real Friends’ go further in undermining the deity Kanye; overexposed 3am synths collide with self-pitying narratives of failure. “I guess I get what I deserve, don't I?” he ponders.

So it continues – the ego is stoked (see ‘FACTS (Charlie Heat Version)’s overexcitement at shoe sales) only to be deflated (Kanye is barely there on dance to the death closer ‘Fade’). Once again, Kanye has released music filled with contradictions and confusion. Once again, it’s like nothing heard before. Once again, it’s good to have him back.

-

8Mark Ward's Score

-

2User Score