Do you remember a time when everything was better? Do you believe in a place in which all troubles evaporate? If yes, you are indulging in Edenic thinking and should probably wash your hands. First formalised by Carl Becker in a 1931 lecture. Edenic mythmaking is the process of imagining that there is somewhere a perfect time or place, always displaced and deferred, which casts a sickly comparative light over the time and place you actually inhabit.

Particular Edens often hark back to a previous time; a golden age in relation to which the present is nothing but a deformed growth to be pruned. Whether it’s the BNP/Daily Mail’s whitewashed moral England of yesteryear, or an elderly punk proclaiming the incomparable purity of some ‘76 revolution, this nostalgic impulse is everywhere to be guarded against. Edenic thinking can also look forward in time. The Christian story promised us a next world in which we might finally stretch out in nice white robes if we could just put up with being bent-double and shit-stained in this. Marx humanised matters by providing a blueprint of a reachable utopia on the horizon, no less Edenic for its political purpose. Edens do not have to be explicit: scratch the surface and most popular music will reveal its Eden. For twee it might be childhood, for rave a communal transcendent space, for folk a Ruritanian retreat - the promised land is a subcutaneous mirage which gives shape to our deepest yearnings even as it disappears over the horizon.

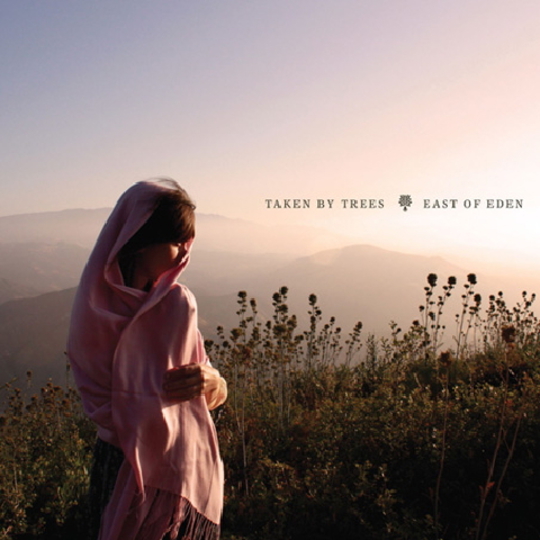

And, as East of Eden acknowledges, Edenic thinking can also look sideways to imagined geographies. Recorded by Studio’s Dan Lissvik, Victoria Bergsman’s second album as Taken By Trees, after her departure from The Concretes and profile-enhancing guest on PBJ’s Young Folks, sees her relocating both her music and her practice to the Pakistani capital Lahore. Working with local Sufi musicians to create a slight and graceful collection of twee Scandi-folk tunes set to South Asian instrumentation, she achieves a steadiness of fusion that holds the two musical cultures in productive tension without ever feeling forced or self-conscious. And along the way she takes care to chart the undermining of her own Edenic myth.

From the opening lines on ‘To Lose Someone’, with its syncopated sitar ascensions and descensions (arohana and avarohana) which closely recall The Stones’ ‘Paint It Black’, Bergsman intones in her soft Nicoisms “I lost you in the crowd / in an unfamiliar town”. If Eden is supposed to be as innately comfortable as a home, then this disappearance of what you know into the palpable difference of the new place is an awkward reality.

The clearest exposition of the Edenic appears on ‘The Greyest Love’, where over a West Coast-facsimile of lolling sunshine pop she croons “When you’re outside / all you want is in / when you’re in / all you want is out.” The corrupted present, ever-exilic, the continual desired escape to an elsewhere – here the Edenic dynamic is played out in an elegantly mournful dissection of an ex-lover’s disposition.

‘My Boys’ is a subdued acoustic reworking of Animal Collectives ‘My Girls’, the spiralling electro-renaissance synths of the original replaced by a harmonium, with its distinctive Indian drone reeds, amid a delicately clambering patter of tabla and plucked strings. The lyrics which Panda Bear (who provides guest vocals elsewhere on ‘Anna’) wrote as an Edenic hope through simple living - “I don’t mean to seem like I care about material things like social status / I just want four walls and adobe slats for my boys” - are jabbed with a dose of reality by the gender reversal. As well as being unable to recruit any female musicians in Lahore, Bergsman confessed in interview to her own difficulty with adjusting to women’s given roles, where on the street she reported feeling 'as if men owned you'. In addition the pointed shots of Bergsman self-consciously fingering her hijab headscarf in the documentary that accompanies the album (which, incidentally, in this context might be read as a nod to sangeet, the Indian inclusion of visual element of dance into the word for ‘music’) give us a clear indicator that, like the place she came from, Eden was certainly not so perfect as to obviate the need for a gender protest song.

The twee stomp of ‘Watch the Waves’ sees the bansuri flute making one its regular appearances, trilling in chromatic complexity over ripples of glockenspiel and flat footed sitar, tabla, and dhol, propelled by insistent handclaps. Here Bergsman is taken to the ocean by someone she begins to realise she loves, until she is clear she “will love you endlessly”. It is a rhapsodic testament to the power of place to invoke feeling.

For final track ‘Bekannelse’, Bergsman reverts to her native tongue, and in ghostly chants beyond a single thin drone retells the Herman Hesse poem of the same name, which according to Bergsman translates as ‘Confessions’. From a young age Hesse was drawn to an exoticised India, writing amongst other novels Siddhartha, a retelling of the life journey of the Buddha which mirrors Hesse’s own search for spirituality through an escape into Indian theosophy. Just as Bergsman, in spiritual terms, finally confirms her acceptance of the present and rejection of Eden by concluding that "mysticism can be found anywhere”, Hesse’s Siddhartha arrives at the same. In a river he finds an elevated self-identification. He realises that just as he is, "the river is everywhere at the same time ... and that the present only exists for it, not the shadow of the past, nor the shadow of the future ... everything has reality and presence.” It is not upstream nor downstream. It is not a was and not a will be. The only thing is presence and the present. The modest conclusion to a modest and warm album, is that Eden might be closer than you think.

-

8Daniel B. Yates's Score