A decade has passed since Half Man Half Biscuit, no minor cult concern themselves, uttered the line: “We’re just sitting, listening to music, drinking tea, talking about the Palace Brothers, Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, that kind of thing” on their track, ‘Emerging From Gorse’. Five years on, Jeffrey Lewis released ‘Williamsburg Will Oldham Horror’ in which he pondered Oldham’s place in the artistic firmament before being raped by him in a New York subway. These two examples serve to illustrate both the level of respect Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy has held all this time, and how profligate mythmaking has followed in his wake. From the early years, when he slipped between monikers on a near album-by-album basis (Palace, Palace Music, Palace Songs, Palace Brothers), to the decision to settle on the Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy alter-ego, Will Oldham has been his own mythmaker-in-chief. The policy has enabled him to slyly sidestep the focus on personality and personal life that dogs so many a critically acclaimed singer-songwriter - the brooding, increasingly-bearded Billy holding far more appeal than the few biographical details that can be gleaned about his brilliant creator.

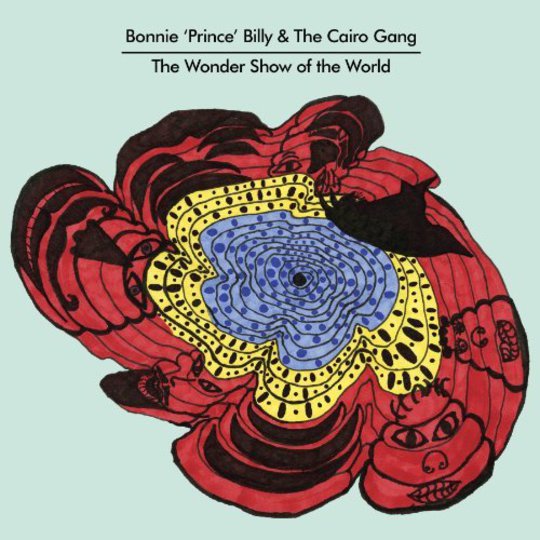

On The Wonder Show of the World it allows Oldham to furnish his vocals with the barest of instrumental accompaniment - songwriter shorthand for sincerity - without ever openly admitting us into his soul. Even as he writes and sings in the first person, Oldham always holds his audience at a point of remove. A fairly successful actor in an earlier life, he still plays a character every time he steps out on stage. The distanciation he attains through the formal device of the Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy figure allows Oldham the freedom to explore whatever ugly territory he chooses, return it in its purest form and yet remain untainted by it. The Wonder Show of the World stands with 2003’s Master and Everyone and Superwolf, his 2005 collaboration with Matt Sweeney, as the works which leave him the most exposed vocally, but we seem as far away from Oldham as ever. On ‘Teach Me To Bear You’, it seems at first impossible to not imagine Oldham himself addressing his parents in the line “I sang away the name you gave to me”, yet check the narrative construction of the song and such a reading is unworkable.

Oldham has made the point that the plethora of name changes adopted in the early years served to signal that each album was a very different beast, and this has remained the case in his output even since he assumed the guise of Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy. Each track of each album is recognisably part of a larger whole, and often this has been due to the various vocal foils he’s pitted himself against. Here he sets Billy against Billy: multi-tracking his own voice as a harmonic device throughout.

The chorus of Oldhams are sparingly introduced at the conclusion of opener ‘Troublesome Houses’. They appear joyously at the conclusion of a lyric that typifies the paradoxes at the heart of so much of Oldham’s output. He has always found beauty in the darkness, just as his lightest moments are underscored with ugly realities. He can’t help but mix salt with the sugar, and his warmest love songs often read like filthy jokes. ‘Troublesome Houses’ opens with the ultimate in mundanity - “I once loved a girl” - but is immediately subverted: “but she couldn’t take that I visited troublesome houses”. The dissolution of the protagonist’s moral universe in ‘Troublesome Houses’ has been carried by a single line of melody, a tune of rare beauty picked up and passed around by the players: the vocal followed by the guitar line, the bass completing that. The sordid implications of the lyric leave its protagonist without a family or anything in his life save those troublesome houses, but ironically it is here that the celebratory choir of multi-tracked vocals appear. Even at his darkest moments, we know Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy has always been a man with a love for everyone he knows.

This love for everyone applies equally to his musical influences. Even as he may have attracted the most immutable musical snobs to his cause, he has led with a resolute egalitarianism. A man as keen to cover Mariah Carey as PJ Harvey, he has been as comfortable in Kanye West videos or R Kelly hip-hoperas as in independent movies by Harmony Korine or Kelly Reichardt. The inter-mixing of that perceived as high and that deemed low culture, or the hip and the square, is present in the sprinkling of musical reference points on The Wonder Show of the World. Echoes of Elton John are as common as those of Leonard Cohen.

From the early wildness, all dishevelled bellows crashing against harmonies as melodies fought to deliver their favoured time signature, Oldham has honed his songcraft to a deceptive level of simplicity. Of course, this has much to do with his choice of collaborators and, lest we forget, his collaborators here receive a credit as co-authors of this album. Emmett Kelly (who has solo releases at The Cairo Gang) and Shahzad Ismaily have both contributed to Oldham’s music for some time and here the three weave gloriously tight patterns despite no discernable rhythm section. ‘Troublesome Houses’ has the most obviously intricate arrangement, but the detail present in each piece here impresses. ‘Teach Me To Bear You’ is carried wholesale by Oldham’s voice, giving the feel of an old time spiritual, before a swollen Nashville guitar line adds meat to the bones. ‘That’s Where Our Love Is’ begins with a rudimentary folk strum, before flourishes of melodica, steel guitar and the lightest of bells gradually reveal the song’s harmonic depths. The Spanish guitar of closing ‘Kids’ recalls some painfully sincere Seventies songwriting, but achieves a kind of greatness through the power of Billy’s voice, or rather his many voices twisted together. There are ten fine new songs here, each beautiful and sorrowful, sparse and complex, sacred and profane: this is what to expect from a new record by Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy.

-

8Mark Ward's Score

-

10User Score