Two hundred-and-twelve years ago on a cluster of rocks in the Irish Sea, two lighthouse keepers met their doom when Howell, a cooper, thought he’d be suspected of workmate Griffith’s accidental death. His solution: lash the body to the outside of the lantern in the hope of attracting help, and not accusations of murder. Alone on a lighthouse with a body and intense storms? What could go wrong?

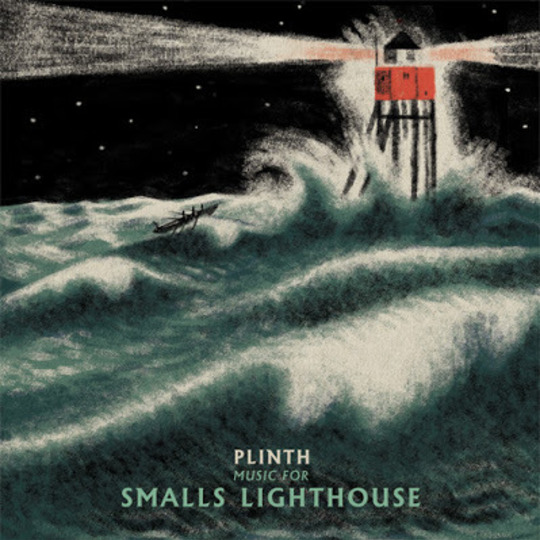

Three years ago, the story of Smalls Lighthouse got a new lease of life from Michael Tanner, aka Plinth, whose woozy but ethereal record of strings, early pump organs and nineteenth-century Dulcitones was released on handmade label Second Language. The run of 150 hardbacks sold out in a server-jamming flash, so step forward cult label Clay Pipe with a 500-strong vinyl reissue complete with booklets, short-stories and vivid artwork from Frances Castle to help you relive the horror of Smalls Rock at your leisure.

A murky neo-classical album, Music For Smalls Lighthouse plays like a salt-soaked requiem, perfectly capturing the inevitable breakdown when you’re alone with a body 20 miles off Wales. The opening ‘51º 43’ .23 N 05º 40’, 10 W’ begins with a crackle of rain and a clipped glockenspiel melody - think the Grandma’s House titles - before fading into church organs, then piano, then waves and creaking timber. It dispels any Fireman Sam jokes of two blokes living in a lighthouse, and sets up the darker ‘Message in the Village’ whose sloshing water, crow caws and 30mph wind ensure the only people who could chill out to this are surfers - the nutty ones who think nothing to wearing a wetsuit on the train or having a quick dunk in a sewage outflow. Tanner’s miasma of accordion shanties and blurry, drinking hole piano shines a light on the title: the first successful message in a bottle was sent from Smalls, written by workmen trapped on the timber and iron structure. Like Tanner’s horror soundtrack it took the dignified approach, reading “Immediate assistance to fetch us off the Smalls before the next Spring or we fear we shall all perish, our water near all gone, our fire quite gone and our house in a most melancholy manner”.

If that feels like an omen then it’s proof of Plinth’s ability to work a narrative into his lo-fi instruments and waves/whirlpools/eddies: he’s not out to frighten but to spin a good yarn, doing it just with as much melody as is necessary. Clouds of glass chimes clear for guitar on ‘Solicitude’, capturing a moment between storms when the sea probably seemed calm, and the unraveling Howell wondered why no help had come from the mainland, remembering the fate of those workmen. ‘Dawn Reflects in the East’ creates a darker air with ambient fog, tolling bells and strings that gradually dominate - just the thing to take the edge off when you’re alone on a rock with a blazing light, your workmate’s body outside the window in a box you built from sideboards.

The most satisfying element to Smalls is how it resists descending into all-out darkness as Howell’s fate comes to its end. Although the album relies heavily on the eerie sounds of the Welsh coast, Tanner avoids recording a force seven gale for ‘The Beckoning Arm’, the album and the story’s dark centrepiece where distant thunder, a high C, gulls and tapping are all that’s necessary once you know the significance of the title. Having watched storms gradually crack open Griffith’s coffin, Howell became convinced his dead colleague’s arm was waving to him, literally beckoning him out into the wind and waves to die. Tempered by the lighter ‘Sirens’ where vocalist Autumn Grieve sings away in vowels, it offers a calmer interpretation of Howell’s demise and his ranting, white-haired mania when he was eventually picked up by lifeboats. It’s this almost soothing approach that turns Music for Smalls Lighthouse into an authentic fireside wife’s tail, up there with Jon Brooks’ Shapwick for its balance of the macabre and the cosy. Best enjoyed with a stiff whiskey, treble glazing and an appreciation for dry land.

-

8George Bass's Score