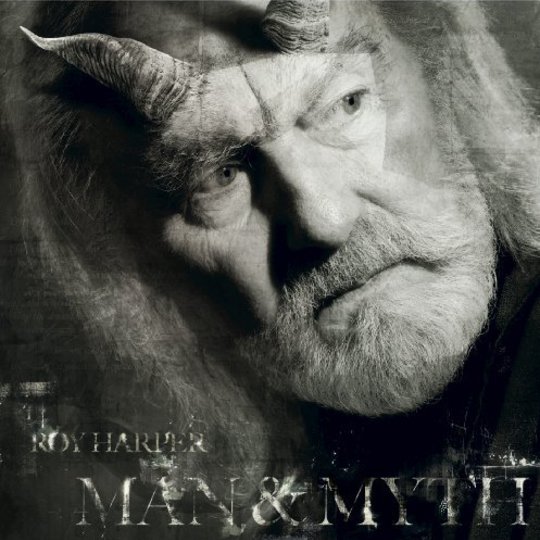

Roy Harper is renowned as something of an awkward bastard. When the world was bobbing its long hair and shaking its joss sticks to three chords and the truth, troubadour Harper was releasing the likes of 1973’s Stormcock, a 40-minute-plus album featuring just four songs of jazz-inspired epic folk rock. When signed to EMI and primed for the mainstream in the Seventies he managed to contract a blood disease that nearly killed him and while signed to Chrysalis in the USA a few years later he apparently attempted to slip past them an album cover that depicted Harper himself walking on water, a bearded, English Christ.

Here on his twenty-third studio album and first full length in 13 years, Harper is no less an outsider than he’s ever been. Yet the testimonials of love from the likes of Fleet Foxes, Joanna Newsom, Johnny Marr and the increasing public knowledge of his past collaborations with Paul McCartney, Kate Bush and Pink Floyd may perhaps this time tip him fully and finally into the role of Respected Elder Artiste.

Man and Myth is no less ambitious than its portentous title suggests and that’s not just because there are two songs that run past seven minutes and a centerpiece that runs for nearly 16. On ‘Time is Temporary’ a gorgeous two-chord arpeggio accompanies Harper’s whispered vocal before a flute trill segues into pinched, halting violin changes that move in strange, unexpected ways. Nick Drake strings throw bronze into otherwise sparse corners and finally give way to a banjo-spiked coda during which Harper unnecessarily repeats the song’s title until it sounds shopping list banal. This is not some old folkie strumming out his semi-retirement but a man still striving to shed the shackles of genre, sometimes getting it right, sometimes not.

His songwriting smarts are sometimes startling as on the unusual, wrong-footing, unresolved melody of opener ‘The Enemy’ which kicks off with a Dylan acoustic rattle and somehow withstands a session guy guitar solo. Harper’s emotional delivery veers between sadness, desperation and being puffed up, robin-like, with smugness – sometimes in the space of just one line. That it’s possible to really enjoy a song that contains trite lyrics like “We don’t live in our villages any more / Metropolis is home…where wildest politicians roam” is one of the baffling tenets of Harper’s mercurial greatness.

Harper’s voice is incomprehensibly strong throughout. To hear a 72-year-old man go from full-throated roar to a regretful whisper as on ‘January Man’ which ends with the line “Lad and lass, into the long grass” in delicate, touching falsetto, is not just a surprise but a show of force and power on Harper’s part too. He’s surely peacocking a little here, and why shouldn’t he?

The heart of the record lays, strangely, within the incongruous Crazy Horse style rocker ‘Cloud Cuckoo Land’ which has Pete Townshend throwing out some Neil Young distortion and Harper sternly observing: “The punters gather at prime time on the flatscreens of their dreams / To vote for dumb celebrities”. There’s something of the Ray Davies to this attitude – something of his brilliance and also something of his less appealing backward looking tendencies, his smarmy, sometimes imperious lecturing. That it has an exciting, wailing saxophone solo and a blurred, cacophonous climax that Harper rounds off with a Partridge-esque payoff line should serve as the surprise that is no surprise at all. It’s excellent, it’s annoying, it’s perilously close to unique.

The best song here is the aforementioned 16-minute epic ‘Heaven Is Here’ which describes the tale of Jason and the Argonauts from the point of view of an Argonaut and is obviously brilliant. Sparse, gorgeously delivered verses build with Tony Levin-style rolling bass (actually played by Tony Franklin) that are, despite their inherent silliness, and despite lines like “Jason said you must sing your song / so I sang my heart” – genuinely powerful and legitimately epic. The second part of the song, album closer ‘The Exile’ ramps up into full Floyd and signs off “We were lost forever…” as Harper intones a personal apocalypse.

There may be nothing here that pricks emotion like ‘When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease’ (the song played on Radio 1, at his request, on the occasion of John Peel’s death) and this may not be the truly brazen, bold Harper of the Seventies but it’s a record of reflection, of experimentation, sometimes of egotism, often of near-mystical sadness. It’s a record that could perhaps drag Harper into the spotlight of reverence from the public that’s previously only been afforded him by fellow musicians. It’s always the awkward ones, the ones that don’t quite fit, the ones that try to walk on water, that make the most intriguing art.

-

7Matthew Slaughter's Score