Vince Staples is not messing around.

In fact, in the three years since Hell Can Wait, he’s been nigh on relentless. Where that EP was a warning shot – fuelled by the power of fresh perspective, but marked as a cut above by wisdom earned the hard way – Summertime ‘06 felt like a full-on artillery bombardment.

Over the course of 20 tracks, Staples – guided by Kanye’s former mentor, No I.D. – pulled off the rare feat of creating something both epic and ruthlessly incisive. As ‘Señorita’ put it: “just focus / I’m tryin’ to paint you a picture” and Staples delivered with plenty to spare, sandwiching a tapestry of life, love and loss in Long Beach, CA into a taut, often claustrophobic, 60 minutes.

Since then, his sights have shifted this way and that, with Staples projecting the struggle of figuring out your next steps in public in real-time. Collaborations with everyone from Schoolboy Q to James Blake represented an opening of horizons; last year’s stellar EP Prima Donna and accompanying short film built a vision of a restless mind at work.

And then, on the eve of his second record, Staples declared that he wasn’t just looking for his next step anymore. He could see the future. 'We making future music. It’s Afro-Futurism. This is my Afro-Futurism. There’s no other kind.'

Which brings us bang-up to date. A useful thing to be since, in the case of Staples and this record in particular, context is king.

Because, in short, Big Fish Theory is the album of 2017.

Not necessarily the best album of 2017 (we’ve hopefully still got six months to go to decide on that), but the de facto album for our times. Over the course of 12 tracks, Staples lyrically and sonically nails the dizzying bipolarity of a world that seems to build ever more momentum with each daily rotation on its axis.

First port of call in breaking down what I mean? The production and sequencing of the record. Hold onto your lunch, because from start to finish, Staples sets about swerving wildly from minimalism to maximalism at the drop of a hat. And the results are electrifying.

Opener ‘Crabs in a Bucket’ is Justin Vernon-produced but undeniably Burial-indebted, all crisp hi-hat lightning strikes amidst stormy atmospherics and sludgy bass. Just when you’ve got the gist though, ‘Big Fish’ arrives to switch things up. On the surface-level, the irrepressible bounce of its lowrider-primed bass and sticky Juicy J feature (“I was up late ballin’ / Countin’ up hundreds by the thousand”) is almost radio-ready.

But in Staples' hands, that hedonistic energy is drained and revealed for the veneer it is. If this is party music, it’s party music for zombies. “If you wanna be the boss you want to pay the cost”, he raps at the end of the second verse, echoing a truth handed down from Snoop Dogg: success always has a price of entry.

From this opening one-two punch onwards the stage is set, but Staples ensures its one you never quite get a sure footing on. The pace is set high. Tracks are densely packed with ideas and yet rarely tick over the three-minute mark in length. A smooth R&B feature from Kućka collides with abrasive, post-Death Grips dissonance (‘Yeah Right’). Chiptune treble butts heads with pounding bass. Beats drop out entirely one moment only to return at ear-bleeding volume the next (‘Homage’, ‘Party People’). A sample of an Amy Winehouse interview is left to twist your heart for a full minute (‘Alyssa Interlude’). Guests as far-flung as Damon Albarn and Ray J pop up on the same track (‘Love Can Be’).

Taken altogether, the effect is one of unsettling sonic extremity. But then again, what better way to capture the extremity of unsettling times? Well… perhaps Staples lyrics.

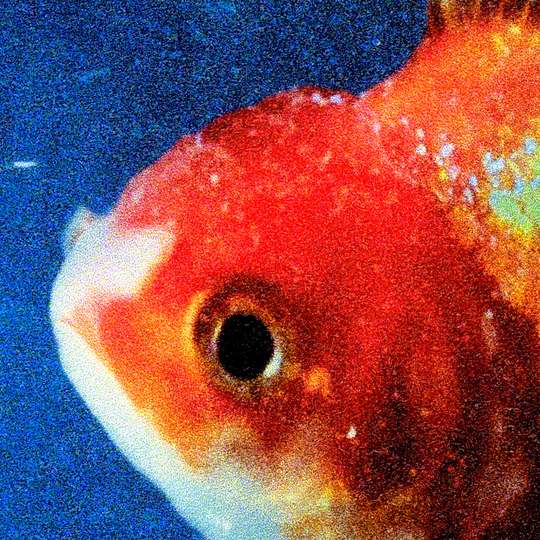

If you’ve seen the video for lead single ‘Big Fish’, you’ll find Staples precariously perched on-board a sinking ship. In shark-infested waters. Which is essentially his worldview in a nutshell.

From his “past misfortune” on the streets of Long Beach to his “déjà vu from my bayside view”, Staples is a man who has seen both sides of the equation and discovered what he suspected all along: the math doesn’t add up.

But rather than tucking into a hearty diet of needy, rich boy self-loathing á la Drake, Staples looks at the world like he’s wearing the shades from John Carpenter’s They Live. He’s seen the ugly truth and he’s to share it through a mixture of searing irony and raw honesty.

From the off Staples is “feelin’ like the world gon’ crash”, worn down by the “crabs in a bucket” that would rather pull everyone down than let anyone succeed, so by the time you reach the sarcasm-drenched ‘Party People’ you’ve got the picture (“Move your body if you come here to party, if not then pardon me / How I’m supposed to have a good time when death and destruction’s all I see?”).

And yet this is no miserablist slog. Lines like the above are delivered in a knowing, underhand register, playing up the wit of a gloomy perspective in a superficially bright, shiny world, and elsewhere Staples’ subject matter and delivery change-up constantly.

He runs the gamut from full-on political raging on ‘Bagbak’ (“We need Tamikas and Shaniquas in that Oval Office/Obama ain’t enough for me, we only getting started”), to heart-rending confessional on ‘Alyssa Interlude’ (“Sometimes, people disappear/Think that was my biggest fear/I should have protected you”).

At the heart of it all though is ‘Yeah Right’, where all the disparate elements milling about in the pond of Big Fish Theory come together in one abrasive cry for realness in a fake world. Co-produced by PC Music’s SOPHIE and Flume, the track bangs, clangs and clatters like a scrapyard, and Staples takes on the mantle of wrecker-in-chief with vindictive glee.

One verse dedicated to cutting through the lifestyles of the rich and famous to the cold reality underneath (“Pretty woman wanna slit her wrist […] Pretty women want a new ass, new lips”), the other to dismantling rap clichés (“Is your house big? Is your car nice? Is your girl fine? Fuck her all night?”). The delivery is sardonic (“boy yeah right, yeah right”) and the impact is atomic, probably bringing back the cold sweats rival rappers only just got over after Kendrick Lamar’s infamous ‘Control’ verse.

Then, as if summoned by that very reference, Lamar himself pops-up on the third verse, a deus ex machina who’s dropped in just to twist the knife some more with a braggadocio-rich feature. All of which brings us back to this album of 2017 discussion.

These two very different rappers share a few key things in common – their West Coast roots, the pointed realness of rapping under their own names, the happy coincidence of rising to ascendancy in the same era – but it’s their shared pre-apocalyptic perspective which most intrigues.

If Kendrick Lamar’s niche is as prophet of the end times, spreading the good word via The Book of DAMN, Staples is its diarist: a contemporary Samuel Pepys urgently scrawling his experiences down as the city burns around him. Or, as he puts it: “what I do is create [a] gallery through an album or through a music video to showcase the different bodies of work I created during a certain period of time.”

The result is a vision of a world in which decadence is just another form of desperation in a desperate world, and it’s the knowledge of this that captures Staples attention. Success is a kind of forbidden fruit (“Adam, Eve, Apple Trees / watch out for the snakes, baby” as ‘745’ puts it) that, when bitten into, reveals that the walls of the garden closing in around you.

This is the titular Big Fish Theory, the idea that despite being at the top of his game, a fish can only grow as big as the size of their tank. To Staples the rap game represents 'a smaller, facilitative space' to pop culture, where rather than truly having a chance to flourish in the wider world, these “larger than life” characters are trapped 'in a smaller world', left to stifle one another as “crabs in a bucket” through corny rap beefs and dissatisfying attempts to crossover with guest features on pop tracks. Staples though, is doing his level best to smash the goldfish bowl.

Nearly half the length of his debut, Big Fish Theory is tightly-wound and laser-focused, yet covers a huge amount of ground, simultaneously showcasing Staples at the most pumped-up and most fragile we’ve yet seen him. His word play is spectacular even when his flow isn’t at its most natural. His subject matter is powerful, dissecting race, religion, rap and much more with intelligence and wit. His production choices are often thrilling, with the only moderate disappointments being tracks that don’t push the envelope to quite the same extent like ‘745’ and ‘SAMO’.

In short, as ‘Homage’ puts it best “I’m on a new level, I am too cultured and too ghetto”. Stapless world of desperation, danger and decadence is deeply involving yet hugely entertaining, and represents another huge stride forward for an artist that can only move in giant leaps. He might not be ‘Mr 1 through 5’ just yet, but he’s not playing that game anymore anyway.

-

9Christopher T. Sharpe's Score