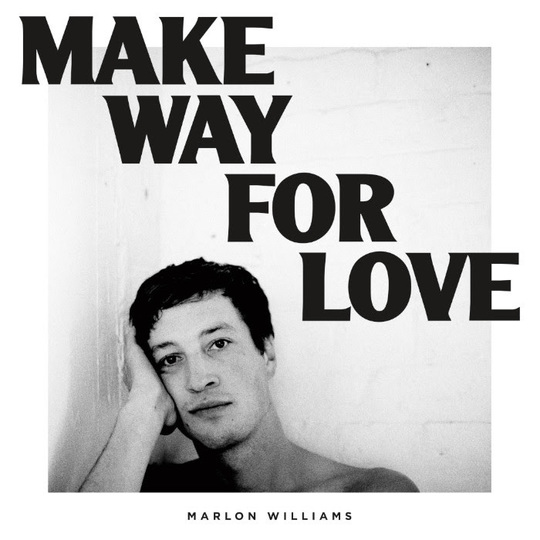

Marlon Williams’ star is one that has long been established in his native New Zealand and surrogate home of Australia, and has been rising in the Northern Hemisphere ever since the release of his impressive debut LP in 2015. He is renowned for his overwhelmingly beautiful voice, effervescent support from his band The Yarra Benders, and an old-school commitment to the grassroots of country folk. Whilst there is no doubt about his ability as a singer and musician, question marks still remained about his writing capabilities.

Written after a breakup from fellow singer-songwriter Aldous Harding, the album explores a path so well-trodden that it’s formed its own valley, leaving few resources to be mined originally. Yet, anticipating the cynical sighs of exasperated consumers and critics alike, Williams has at stages defied expectation, musically and thematically. The narrative arc is not particularly idiosyncratic – we start with a forebodingly happy summer’s scene, before the cracks appear, then the bulk of the album deals with the bleak aftermath (jealousy of other guys, late night calls – you know the score), turning the spirits around just in time for a final optimistic redemption. However, the anecdotes and experiences within stand proudly independent from the canon – alongside emotions of grief and solitude are ones of stark honesty and guilt. This is best exemplified in the apologetic confessional ‘I Didn’t Make A Plan’ where he declares he “didn’t make a plan to break your heart, but it was the sweetest thing I’d ever done”, before claiming that “he won”, though we realise immediately that this is a painfully hollow victory. Elsewhere, he addresses an ironic situation where a jeweller has become ‘a very wealthy man’ thanks to there being so many lovers similarly grovelling.

As for the songs themselves, it is a similar mixed bag. There are moments of sheer beauty, from the dappled summer sheen of opener ‘Come to Me’ to the stark piano ballad of highlight ‘Love Is A Terrible Thing’, around which the mood of the album pivots. The showstopping standout is ‘Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore’, which intriguingly exploits the convenient career-sharing of the ex-lovers and brings them together for a duet of exquisite openness. The mutual respect and care between Harding and Williams is evident, as they wrestle with the paradoxical reality of being split without having any obvious bad blood (“What am I going to do when I’ve seen that you’ve been crying and you don’t want no help from me?”); Williams is then left alone for the final third to contemplate this cathartic confrontation. In other parts, though, the songs become at best forgettable and at worst clanging, such as ‘Fire of Love’ which strives artificially for sonic versatility.

Whilst we are provided moments leaning towards bleakness, there is never the gut punch that such an album requires. Minor keys and changes of tempo indicate misery without sufficiently supplying it. You might blame this lack on an accident of geography: the recurrent imagery of sea and water provides wistful images of isolation, but they are noticeably Californian or Australasian waters; perhaps, if he were faced with the frigid flows of Scotland that have inspired so many songs of piercing desolation, he might access the depths that would have elevated the work. The listener is left in no doubt that these songs mean a great deal to their writer, but we are not always convinced of their significance to us: the pit of the stomach is never challenged as forensically as in ‘Bird On A Wire’ or ‘Jealous Guy’, both of which Williams has so poignantly covered in the past, and which wouldn’t have been out of place thematically here.

You get the feeling that Williams has now sufficiently set out his stall. His voice remains an awe-inspiring force, and, coupled with a strong ear for harmony, he is instantly more interesting than most of his contemporaries. With this album, he has demonstrated an admirable ambition to make his albums a coherent piece rather than merely a collection of nice songs. Though the overall effect is sometimes lacking, there are enough encouraging signs to suggest that his future work could produce something truly special.

-

6Tom Lambert's Score