I’ve always marvelled at the Japanese practice of Kintsugi. When pottery breaks, the shards aren’t thrown in the bin, but carefully reconstructed and glued together to honour the object’s mileage and trauma. This beautiful marriage of craftsmanship with deep philosophy is more tangible than the act of writing songs, but in its essence, it’s the same thing. Indie rock stalwarts Death Cab for Cutie even named an entire album after it, though one could argue its principles apply more to their Pacific Northwest peer Pedro the Lion.

Phoenix, David Bazan’s first album in over 15 years under the Pedro moniker, indeed, feels more like a reconstruction than a revival. In my yonder years, I’ve always had a strange relationship with Bazan’s music compared to the artists hailing from similar pastures. Death Cab appealed to my teen angst, Modest Mouse to my nihilism, Elliott Smith to my depression and sadness. Bazan’s former housemate Damien Jurado– who named his underrated masterpiece Ghost Of David after him – was still too erratic for me at the time.

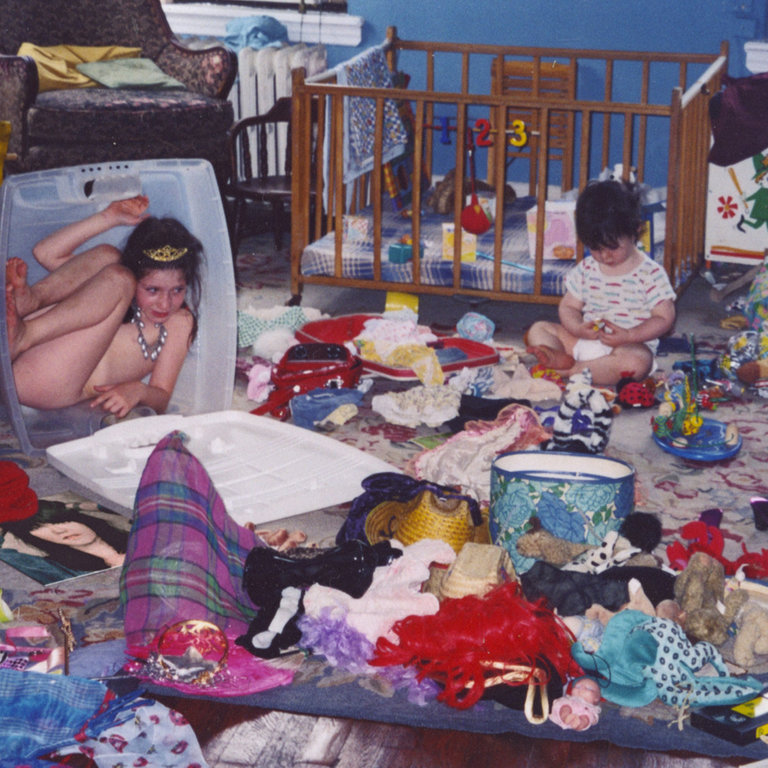

The first Pedro the Lion song I ever heard, ‘The Longer I Lay Here’, struck me in this super intrusive way. It’s a barren lo-fi acoustic track that sounds as if conceived from a messy bedroom, the sunrise acting as intruder peering between the shades. The unprocessed sorrow in Bazan’s weary voice felt almost too real, too immediate. As a youthful, giddy soul, at the time, I ached for music that would crystalize my own pain more eloquently or crudely. Bazan sounded like a lost soul woefully at odds with himself, the solace of his guitar applied as last resort to kickstart something resembling enlightenment. His ambivalence made his music achingly human.

Retrospect can be a funny thing, though. In my thirties, I feel old enough to articulate why Pedro’s music didn’t click with me before. And, more importantly, why it suddenly does now. For one, I can remotely imagine why Bazan had to put the Pedro name to rest. Here is a guy who was insistent on putting his fingerprints on every instrument, every lyric, every vocal take. Making records was a soul search, a quest for a deeper understanding within himself and within his place in the world. Chiseling complex existential questions into clean, sapid refrains has never been Bazan’s forte. It’s reasonable that at some point, it would feel like self-immolation.

Even on Phoenix Bazan doesn’t exactly come out of the gates swinging with ‘I’m baaack!’ fortitude. Opening cut ‘Sunrise’ is a lulling, soothing paintbrush of synths, frayed by a faint static that doesn’t in any way feel intrusive. The restful lurch of ‘Circle K’ – similar to Ought’s ‘Passionate Turn’ – immediately evokes a tender sentiment. Bazan unravels a memory about failing to save up for a skateboard because he spent all of his allowances on candy and soda pop. It takes quite a lot of living to sermonize a dull trip to the convenience store, but Bazan’s husky, world-worn delivery immediately sucks you in. “I spent it all at Circle K //Dreaming that the light would never change” And aptly, there’s no soaring chorus to speak of, as the song spirals out exactly as it began.

That embittered sense of cross-examination is palpable throughout Phoenix, though Bazan doesn’t feel stuck in the ditches like on those introspective early Pedro recordings. For the most part, he sifts through his memory banks with matter-of-fact clarity, leaving it to the elemental power of the music and voice to evoke meaning. The dirgeful ‘Quietest Friend’ carries acknowledgment and acceptance of past digressions: not like a heavy cross, but like an illuminated beacon.

Sonically, out of all the Pedro album’s, Phoenix is by far the most arena-sized in its scope. Even though a lot of his meanderings are rooted in the past, Bazan is keen to hold a mirror up to the notion of unapologetically maudlin nostalgia. ‘All Seeing Eye’ has all the makings of a bona fide stadium rock-belter, but Bazan chooses to embellish his pleas with just a fragmented echo chamber of melodies that sound like samples from a band recording played on a keyboard. It’s a crafty sonic execution of the strange disconnect your feel revisiting your hometown after many years: a vague residue of home that fades amidst constant the rebuilding and mutating.

Which brings us to the place Phoenix occupies within the canon of Bazan’s Pedro the Lion catalog. For one, it shows an artist no longer caught in his own artistic web, but someone watching his past selves struggle from a higher vantage point. ‘Clean Up’ is the closest thing to a fist-pumping guitar anthem as Pedro the Lion has done, as even here, Bazan is only tentatively optimistic (“or even having some fun”). On ‘Powerful Taboo’ he expresses misgivings of ‘good vibrations’, seemingly fully aware of the ‘triumphant return’ narratives that gird most artists coming back from more than a decade of absence.

But even in his so-called ‘hiatus’, Bazan never stopped performing and releasing records. In this KEXP interview, he wryly states that all it took for people to start paying attention, was to perform again as Pedro The Lion. But, like his friend Damien Jurado, stirring restlessness and discomfort have always been both a gift and a curse. Jurado’s latest LP The Horizon Just Laughed reckons with his beliefs and touchstones within times of overwhelming change, and in many ways, Bazan accomplishes a similar awakening from limbo on Phoenix. Its centrepiece ‘Leaving The Valley’ serves almost as Bazan’s sister song to Jurado’s ‘The Great Washington State’, two question mark-protagonists eternally in doubt of the truths they are pursuing.

‘How do you stop a rolling stone / how will you know when you are home?’ Bazan asks himself. Though he may never get a satisfying answer to that jarring question, on Phoenix, he has at the very least picked up the pieces, retracing the origins of his scars.

-

8Jasper Willems's Score