It's been a strange old path for The Lumineers, a band who struggled in obscurity for over half a decade, relocating from oversaturated New York to comparatively peaceful Denver, Colorado, released a monster single at exactly the right time and next thing they knew, they were playing the White House for President Barack Obama. Success is a strange thing. Yes, it gives one the kinds of opportunities and recognition reserved for a very select few, but it also ultimately means a reaction from those who observe it and it is not always positive.

For while The Lumineers, seemingly out of nowhere, found themselves shooting to the top in rapid-fire succession, this also came at a cost. For all the Grammy nominations, Hunger Game soundtrack successes and Presidential name-drops, they also found a media and public obsessed with one major single - 'Ho Hey' - countless comparisons to the UK's Mumford and Sons, who had also exploded in 2012, and having the difficult, slippery, and perhaps now trendy "Americana" tag thrown at them from all angles.

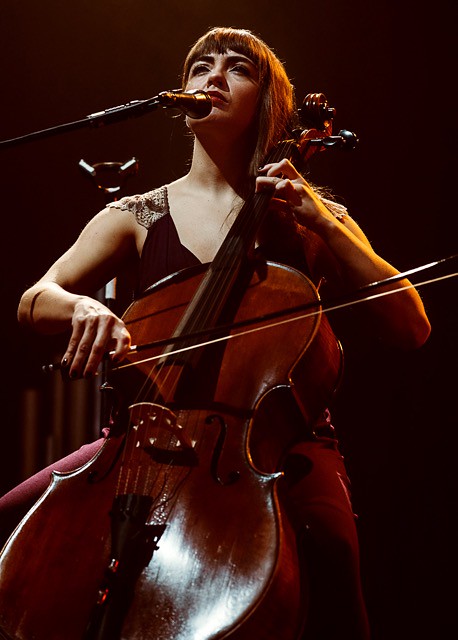

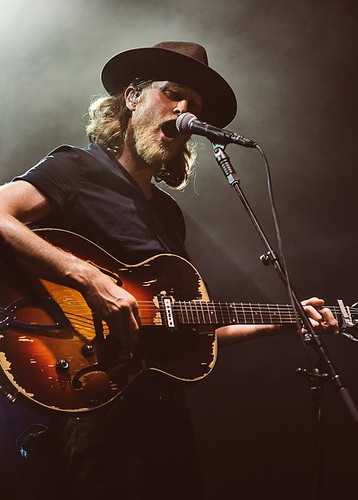

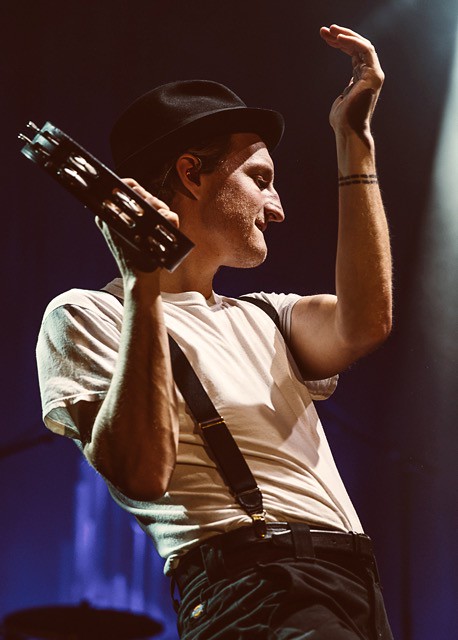

So, after a three-and-a-half-year world tour of success, how did The Lumineers respond to a huge single and being endlessly written off as one trick ponies and part of a particular trend? They sat down, took their time and wrote one of the finest follow-up records for quite some time, easily surpassing their energetic but scatty debut, and quietly releasing one of 2016's most underrated albums. Prior to Christmas, DiS caught up with the three members of the band – lead guitarist and singer Wesley Schultz, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter Jeremiah Fraites, and cellist and all round band glue Neyla Pekarek – in Prague to speak about how they dealt with the monumental, yet potentially shallow, success of their first record and attempting to follow it up, life on the road for large amounts of time, and a changing America and world they faced when returning home.

The first instantly noticeable aspect of the band when meeting them is how humble and grateful they all are, both of their fans – they have been doing small meet and greet sessions with fans after letting them watch their sound check at each show this tour – and the opportunities afforded to them via their support, but also of each other. Though I meet them in three sessions, once with Wes at their hotel, another with Jeremiah and Neyla together pre-gig, and then all of them post-show, they consistently seem optimistic about their music and with each other. There are no egos and no frustration with how their band have been perceived by some to be found here; they are simply a band who haven't forgotten the struggle it was to get to this stage, who are aware of the dangers of success and have taken it in their stride.

"We had around seven years to build up to the debut album so that kind of shaped a lot of our decision making. Luckily, for this second album, people seemed genuinely excited to let us do our own thing with it," Wes explains while talking about following up such a massively successful debut. "It's hard to turn past page one, so many people casually like us due to 'Ho Hey' and 'Stubborn Love', and that's fine, but we wanted to create something more substantial this time around so that people can believe in what we've created. We can't control what people will think of us, and some people will have written us off entirely already, but I’m proud of this second album – it feels like a genuine evolution from the first."

Jeremiah, the band's other major creative force agrees. "I think a lot of people thought of us the first time round as this ‘Mumford-lite, folk-Americana’ pigeonholed band, so I hope people understand with the second album we tried to move away from that. We wanted to showcase that we’re capable of more than just that. We have classically trained singer [in Wes], cellist [Neyla], and I can play lots of different instruments so while a song like 'Ho Hey' can do wonders for your career, it can also stunt people's perception of your artistic abilities."

The band are all too aware of the seemingly endless Mumford and Sons comparisons, as Neyla explains. "The way 'Ho Hey' sounds, using mandolins especially, we certainly felt pigeonholed at the time, but the new record has expanded on it. On the first record, we couldn't do an interview without Mumford & Sons being mentioned or being compared to them, and while we consider them friends, we certainly had no prior relation to them; it was mostly coincidence. On this tour though, it seems to have stopped and people understand we are much more than that. We understand too, though – we’re sure our friends’ bands back at home in Denver now keep being asked about or compared to us."

It’s ironic, because given the physical, geographical distance between the bands and their coincidental timing, the press seemed to want to make a trend happen rather than the other way around. "On the first tour the three of us used to do all our interviews together, and I [Jeremiah] never felt pigeonholed until we spoke to the press who would immediately launch into ‘So! Mumford and Sons huh? Sick!’ But once we got away from that it didn't affect us."

"There's also the wider issue of labelling, given there's no fixed idea of ‘folk’ or ‘Americana’, although we can say for certain that we are not a ‘country’ band," Neyla explains. "I think ultimately Wes is just trying to tell stories which do fit into the ‘Americana’ idea more than any specific sound or description really could."

When listening to The Lumineers sophomore album Cleopatra, it is difficult to argue against this. While their self-titled debut caught an almost fluky intensity in it's biggest moments – the aforementioned 'Ho Hey' and 'Stubborn Love' – the rest of the album is a scattering of interesting ideas and moments, but they don’t necessarily hold up as a cohesive album. On Cleopatra however, there is a clear, noticeable intent to build on the first album’s strengths and turn them into a proper, storytelling record which, while it certainly doesn't have an overbearing concept, holds together much better as a full-length piece of music.

"We knew people had been casual about it because people almost sounded surprised about how good the first record was" Wes jokes. "So this time, we found a great way of writing together; we shared a house and treated it as a 9-5 and insulated ourselves."

Though I meet Wes and Jer (as he is referred to by the band) separately, they seem in agreement about each other's role in the band. The former is very much influenced by the more classic American folk/rock singer-songwriters, your Springsteens, Dylans and Pettys, while the latter is influenced by a broader spectrum. "I think it's more interesting to take bits from everywhere rather than just solidly listen to and be inspired by one genre. Radiohead, Björk, and Aphex Twin, for instance, are probably my favourite acts, and they all take influences from unexpected places."

Wes confirms that "I was very traditionally influenced, whereas Jer is much more out there, and I will allow myself to go along with him because it makes our music much richer. Our strengths don't necessarily overlap; Jeremiah is way more interested in art and creating sounds, but if we didn't work together we wouldn't be as successful as a band."

On recording the follow-up, Wes asserts how much more focused they were this time. "We were given much more time to record this album. On the first one, we felt like we'd been snuck into the back door of the studio, whereas this time we had six weeks to make the songs as good as they possibly could be. We would focus on one song at a time, and make sure we got the right level of rawness or intensity down on the track."

The band largely credit producer and American Folk Music legend Simone Felice (of The Felice Brothers) for making this a possibility. "He [Felice] was a big help with that, we often call him our shaman. He's a very tapped in, spiritual kind of guy, and it was almost like we were this weird small cult devoting ourselves to creating this record. There would be takes where I would be in tears by the end of them, whereas the first record we were so familiar with the tracks already that it was just ‘boom!’, done, get them out. We got to sink our teeth into the performances, meaning we can translate it easier live and really sink our teeth in."

Despite acknowledging this songwriting and recording process, Wes often describes "the song" as the most important aspect of their album.

"'Long Way From Home', for instance, originally had a piano line from Jeremiah which was so sweet but it was totally at odds with the lyrical content. He was willing to put it aside, so there's a selflessness around us that allows us to work. I wouldn't call it democracy; if anything, the dictator is the song, and we are serving it, so there is no room for personal egos in the songwriting."

Indeed, Jeremiah and Neyla seem onboard with this idea that they are willing to do what it takes to make the song the best it can be. Neyla especially, as self-admittedly not being a part of the initial songwriting process, has to put a lot of her talent and ego aside.

"The cello is used as an accessory in some ways in the band, I rarely need to impose myself on it," she states on her involvement with the record. "So instead, to have something that's mostly pre-written and laid out for you means I often have to scale back... even though I sometimes suggest: ‘But look at this beautiful melody I can play!’ However, as it often doesn't suit the project, it's just a matter of putting aside my ego. I went into the studio for just ten days of the six-week session, but it was very high pressure to get it done in that time."

Jeremiah agrees. "I give Neyla a tonne of credit because here we have a classically trained musician playing an instrument such as the cello, which can be so beautiful that you could add it to any track and be amazed by it. However, we often have to think about how it reflects in the sound. So while we often use it more live, we really the need to scale back on the record. A bigger example was choosing not to use a brass track from (Bruce Springsteen's) E Street Band on the track 'Ophelia' because again, it sounded incredible but it just didn't fit the feeling of the overall project for us."

This is quite an impressive choice, but it's fairly obvious from meeting the band that it’s consistent with their approach to their music: choosing not to use one of the most world-famous brass bands on their album had nothing to do with inflated egos, but in fact was a clear aesthetic choice. It’s refreshing to meet a band who, despite having an extremely successful four-year period, haven't let this corrupt them, and in fact has encouraged them to become more focused on their art.

"Originally I felt like I needed to slay a certain dragon with my art," Wes explains, "but now I have a bit more freedom with it; I'm not really concerned with levels of ‘success or writing five albums in quick succession. Really, I just want to create as much good art as I can that feels comfortable."

Restraint, however, is probably The Lumineers' biggest strength in their music. Even on their debut, the band spoke of how they desired to "be able to play any of their songs acoustically in any space". However, on their second, with more time, money, and effort afforded to them, this was perhaps an even bigger challenge to maintain. Cleopatra sees the band move closer to the spectre of The Boss, despite choosing not using his E Street Band, in a similar way to Arcade Fire. But then the band rarely goes for the jugular, favouring constant movement in their songs to crescendos.

Wes likens this to action movies as an example of our instantaneous culture. "There's a humanity to it I think, whereas if you rush to a crescendo then your life has a crescendo. I feel it is like action movies, whereas our music has a more lasting effect like an indie film. We hate the idea of the ‘drop’; it's too obvious. For instance, Jer's a great drummer, but he doesn't like ‘beats’, he intentionally restrains himself so the songs can be as stripped back, and thus less is more."

The new album's title track and lead single 'Cleopatra', for example, tells the story of a taxi driver from the Republic of Georgia who missed out on the love of her life because she was grieving for her recently deceased father. Wes met the woman while touring the first album, and felt her story seemed completely at odds with a lot of modern, Western culture but highly relevant to what they are trying to create.

"When I heard this story, I wanted to be as fair and respectful about it as I could. I found the idea that she wouldn't wash the muddy footprints of her man off her floor and her acceptance of ‘having a hard life’ really fascinating. Basically, I don't think that lack of spin really exists in American culture, especially now with Facebook and Instagram. My dad was a psychologist and I studied it too at school, so looking at the human psyche is interesting to me and how I can translate that into songs. This woman may have felt like she missed out on the love of her life, but she has a community that loves her and she can be honest with, which I found totally at odds with a lot of Western cultures."

Eventually, I feel I must bring up some less favourable subjects to get an idea of their perception of themselves and also as a band who have spent so long on the road away from home. We meet on Thanksgiving Week which, while one thing for an American band to face – "At this stage, I'd be more surprised to be home for Thanksgiving now," Wes quips – of much bigger note is that it is a week after Donald Trump has become president-elect and Leonard Cohen – a huge influence on Wes particularly – has passed away.

"Oh man, I need intense therapy I think. I generally don't have political discussions with people I don't know well, but I think that has maybe changed now." Wes explains.

"Leonard Cohen passing was separate but still tough, mostly because a close friend of mine also passed away two weeks ago, so it has felt like a particularly dark time personally. With Trump, however, I feel regardless of what you think of him, the main thing to take away from this election is that many people felt like they weren't being represented, and now they are finally being heard whether you like it or not. We are disparate tribes in this huge melting pot in America, and when one tribe's desires get put over others it's dangerously easy to write them off as certain things [i.e. as racist or homophobic.] However, I have family members who voted Trump or didn't vote for either candidate and yet who I know not to be either of those things. I just hope Trump doesn't turn out, or is allowed, to be everything he said he was during the campaign and that it was all a ploy."

When I ask if, given folk music has so often been associated with ‘Protest Music’, it’s something they may end up writing about in the future, Schultz can't deny it as being a possibility.

"In my own family there are gay people but in my extended family, there are also people who do not believe they should exist. I spoke to a friend of mine recently who specialises in political discourse, and he told me the best way to get people to listen to your point of view is to not use numbers or accusations but to tell your story. There's a song on the first album called 'Charlie Boy'; the first line is "Charlie Boy don't go to War" and the hook is about rifles going off as a salute at a funeral. To me, it's not supportive of war, but it's not dismissing it either. I hate being preachy in music; it is far more interesting to tell the story of, in this case, my uncle, and that people of all ilks can feel this song represents them in some way. It's more important to me what the listener takes from it once it's published. So I don't know if I could see myself singing something overtly political, but if there is a story I find interesting to write and sing about which has some political involvement, then sure, it’s possible. It's hard not to become a caricature when you go down that road; it's incredibly difficult for someone like Dylan to write 'The Hurricane' without it being preachy. I certainly think it will be in our collective subconscious."

In meeting the band, one can tell they are very much music fans in their own right. Even when not directly asked about them, Wesley will often refer to musicians such as Dylan and Springsteen, who both make their presence felt during The Lumineers’ set courtesy of a cover of 'Homesick Subterranean Blues' half way through – including Schultz entering the crowd to sing the iconic lyrics – and by choosing Springsteen's 'Atlantic City' to play over the PA after they have finished. While, again, the lack of egos mean he is not comparing himself to their legacy (yet, anyway), it’s easy enough to see how these musical giants have such a positive attitude towards The Lumineers music and position within the current musical climate. When Wes claims early on that he is "not really that interested in success but in creating good art" it’s not difficult to believe him.

While they faced both something of a popular backlash for their success but also for being unwillingly compared to a very separate act, the band have carried on undeterred and produced a much more confident and assertive album. While they comparatively received hardly any fanfare this time – reviews were mixed, presumably because they didn't follow their previous trend – they’ve produced a much more noteworthy record full of well-told stories and strong musical composition.

Regardless of the lack of hype surrounding them now, their performance and fans prove they still have a lot going for them going ahead. They are a force live, a miniature Arcade Fire if you will, but minus the bombast and increasing the subtle flourishes that make this record so impressive. The Prague crowd, to their credit, lap up everything they do, something the band themselves acknowledge and appreciate both during and after the show. While the crowd go absolutely ballistic for 'Ho Hey', placed early in the set with the polite request to "Film us on your phones for this song if you must, but please put them away afterwards", they oblige and remain completely with the band as they play the second album almost in its entirety for their 90-minute set, including during the wonderfully delicate numbers 'Long Way from Home' and 'My Eyes' for which they are respectfully hushed.

It will be fascinating to see where The Lumineers go next now the hype has died down, but the crowds remain and their output gets better. No one in the band appears to be in a rush given the four-year gap between their first two albums, but they are also interested in "extra-curricular activities" as Jeremiah calls it with their music. As we wrap up our time together, Wes explains.

"I'm really interested in this idea of creating a soundtrack for a film that doesn't exist, rather than a traditional Lumineers album next. Taking a break from The Lumineers and then coming back to it once we're refreshed. I can't say exactly what will happen, but we will always be interested in this idea of ‘timelessness’. I think what's also important is that we use our time here well and not try and repeat ourselves. To be honest, I never thought I would be sitting here being interviewed in a hotel in Prague talking about our third album. So I just want to appreciate it rather than want more."

Cleopatra by The Lumineers is out now via Dualtone Music Group. For more information about the band and upcoming tour dates, visit their official website.

Photo credits: Andrew Kelly