The world is a sharp place, and art that serves only to map out its painful edges proves as useful and welcome as Owen Smith’s post-election hubris, or chlamydia, or waking up and realising that Owen Smith’s post-election hubris has somehow given you chlamydia. The scenes that leave a real scar are those that locate the intersection of tragedy and farce; the ragged contours, the poignant moments Simon Reynolds once described as “the exquisite meshing of two contradictory feelings”. It’s driven by characters who compromise the expectations attached to their role, and by proxy, the way we identify ourselves within them. The world’s villains are still easy enough to caricature. But if you happen to fall outside the heteronormative matrix, chances are the heroes don’t look anything like you either.

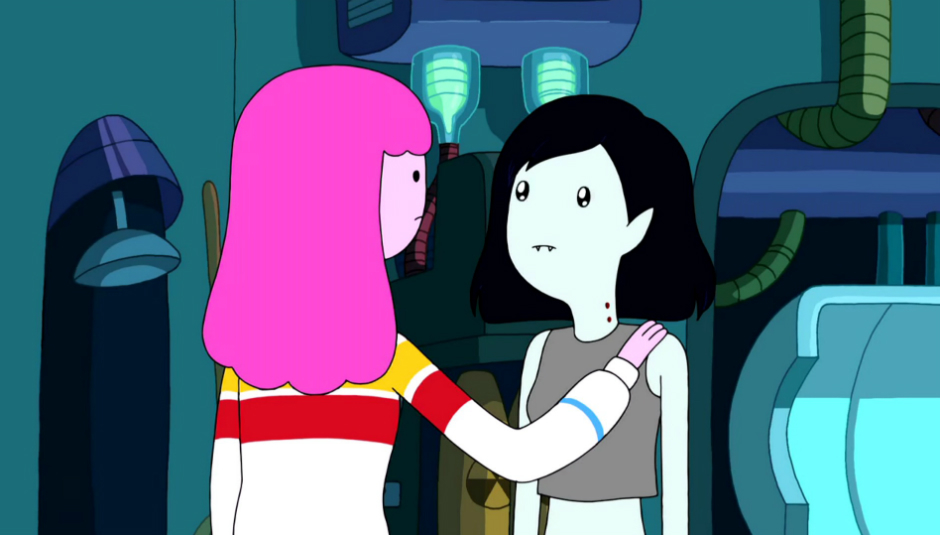

If all of this seems like a painfully long and worthy introduction to a show that airs on Cartoon Network, then you’ve presumably never seen Adventure Time before. Smart, funny and heartbreaking, often all within the same breath, the series is currently airing its ninth and final season. Over the years, the show has pushed boundaries of artistic experimentation within the remit of a children’s television show – and sometimes, television full stop. Characters die. The main protagonist loses an arm. There’s one guy who’s basically a nightmarish screaming lemon, a demographic the right-wing media are still refusing to acknowledge. Notably, the developers went as far as they could to intimate that recurring characters Princess Bubblegum and Marceline ‘the Vampire Queen’ Abadeer had a romantic past; when it aired in 2011, the episode in question (‘What Was Missing’) proved a remarkably late breakthrough for portrayals of same-sex relationships, especially in shows nominally marketed towards children and 30-something freelance writers. Sailor Moon, eat your heart out.

Olivia Olson, the voice of Marceline, revealed in a Q&A that creator Pendleton Ward had privately confirmed that the characters were once more than friends. “I wanted to pick Pen’s brain a little bit. And he says, ‘Oh, you know [Marceline and PB] dated, right?'” She later partially retracted the comments, perhaps under pressure from the network’s panicked upper echelons to make sure that, like the 1930s’ Hays code, homosexuality is always coyly alluded to, but never explicitly acknowledged. At any rate, Ward’s hands were tied: “He’s like, ‘I don’t know about the book, but in some countries where the show airs, it’s sort of illegal.’ So that’s why they’re not putting it in the show.”

But lord, they’re trying. And it’s not just Adventure Time: the final episode of The Legend Of Korra had to tiptoe through its emotional ending, in which female protagonists Korra and Asami are finally revealed to be in love – which, as co-creator Brian Koneitzko admitted, was “hardly a slam-dunk for queer representation.” Steven Universe, the creation of former Adventure Time storyboarder Rebecca Sugar (who came out as bisexual last year), ran into trouble when its episode ‘We Need to Talk’ was censored for suggesting that women might occasionally fancy each other. Even more absurdly, Disney’s Gravity Falls recently had to have a gay couple more or less in the background of a shot re-drawn as a man and woman. When a show bearing the brand of career anti-semite Walt Disney seems less progressive than usual, you know something’s wrong.

One of the smartest ways that animated shows have learned to sidestep such censorship is by skewing gender assignations altogether. Adventure Time‘s B-MO, for example, is never explicitly gendered, but performatively explores different identities, at various times enacting both pregnancy and hyper-masculine Columbo roles without accepting either as natural. Steven Universe has taken this to the next level by literally dissolving its characters’ genders: as well as being essentially aliens, the show’s protagonists are capable of fusing with each other to create new identities. At one point, Steven fuses with his friend Connie, and the scene cleverly plays out different attitudes to coming out – without the metaphor (apparently) becoming explicit enough to provoke the censors.

Outside the world of animation, things were different – or rather, just the same. Suddenly, it became hard not to look at the way Ward and Sugar had quietly ushered in queer protagonists to talk and sing about their experiences, and contrast it with how far behind ‘real’ indie music – supposedly pop culture’s main outlier for progressive, alternative ideation – was lagging in 2011. Arctic Monkeys and The Horrors were still sneering out of leather jackets, and with the odd sanctioned exceptions (primarily St. Vincent), mainstream rock narratives felt decidedly staid.

Fast-forward to 2017, and the gulf only seems to be widening. Cartoons continue to experiment with new ways of incorporating queer voices, while grown-up, mainstream rock bands make painfully slow process. It’s still news when Tegan and Sara, freshly minted with global pop stardom, are bold enough to use female pronouns in love songs. Of course there are cult and underground acts making use of their platform to confront LGBTQIA issues; there has been for decades, to some extent. But they don’t reach the audience of millions that Adventure Time and Steven Universe do. Aren’t there bands out there with the talent and audacity to do what they’re doing – to talk about these issues in a way that hits that sweet spot of funny and sad, smart and emotional, immaculate and roughly hewn at the same time?

Sometimes we’ve got close. It would be deeply unfair to lay all of this at PWR BTTM‘s door, but the allegations surrounding Ben Hopkins earlier this year certainly didn’t help. Finally, it seemed like two musicians who both identified as non-binary were on the cusp of becoming stars, before they got dropped like a hot brick for paying lip service to safe spaces without honouring them. Unfortunately, musicians are real people, and the rock star avatars they represent are drawn from cruder, more fallible stuff. Supposedly.

But really, what’s the difference? Perhaps the likes of Pen Ward and Rebecca Sugar are afforded greater editorial space to manage their personas, with a wider margin for erasing their mistakes. Perhaps it’s easier to cloak your identity in the form of an animated character than to fuse your physical self to an idea of what you’d like to represent. Nonetheless, both earn a living as storytellers; both hold platforms for artistic expression, with room for cultural and political dialogue within them. Both are free to create safer art that affords them a more comfortable life, if they wish.

It’s the rock stars who are playing it safe. I’m looking at my favourite albums of 2017 so far: Perfume Genius stands out as an extraordinary example that progress is being made, seamlessly weaving his own vulnerability as a gay man into bolder declarations of how pop songs can accommodate queer narratives. (Mike Hadreas is no stranger to the censorship of implied gay romance in music clips, either: his video for ‘Hood’ was banned by YouTube for its ‘adult content’ – essentially, two men hugging.) Nite Jewel and Diet Cig are up there. But who else? Music still seems to occupy a rarefied space in popular culture that values vague, cross-market gestures over explicit confrontation, at least when it comes to gender and sexuality.

Even across an eleven-minute episode, these identities can be explored more fully, but music is still an important part of explaining them. On top of that, the YouTube era has democratised the way in which songs are consumed, meaning it’s as easy to listen to a track from a TV programme as it is a chart hit from a touring pop star – and for the generation who’ve grown up with shows like Adventure Time, the latter category holds no particular sway over the former. Perhaps you’ve got a chill playlist that sandwiches ‘Blue Magic’ and the Sugar-penned ‘Everything Stays’ between London Grammar and Daughter, or a breakup mix that finds room for ‘It’s Over, Isn’t It?’ next to ‘Maps’. Maybe you’ve just been tidying the house to a 10-minute loop of that ‘Bacon Pancakes’ / ‘Empire State of Mind’ mash-up. In 2017, they’re all equally valid.

If today’s showrunners can keep pushing messages of acceptance and individual freedom past the executive gatekeepers, musicians can do the same. When Perfume Genius sang that infamous line from ‘Queen’ back in 2014 – “No family is safe when I sashay”, presumably a barbed wink at the censors – it felt like the first time in a long time that an indie artist was making a serious point in a non-serious way. That’s what people like Rebecca Sugar, and to an extent all great comedy writers, understand: jokes are funny when they confound your initial expectations of the scene, and that’s a fantastic vehicle for stretching minds beyond their conceptual boundaries without realising it. More than ever, we need songwriters willing to draw outside the lines.