Growing up in the Midlands during the 80s there was always UB40 in the house. There was always some UB40 in everyone else's house as well. Nowadays, it’s hard to fathom that at one point that this Birmingham-reggae collective were actually good. What’s even harder to remember was that their debut album was actually really good. Amazing actually, full of guttural angst, rhythm, dub, and soul. Perhaps if UB40 hadn’t moved on to being a derivative covers band, Signing Off would be remembered more fondly. Having moved to Berlin over a decade ago, I became re-acquainted with this classic, reaffirming a narrative I had lost about my cultural heritage, reminding me of a time when British music was political and fun.

Now, first things first, I’m not one of those people who can claim to have grown up in an expansive-musical household. Nor can I say, having grown up in a single parent household, that my mother had a great LP collection which was a source of any real inspiration (if you’re reading this mum – sorry). Those UB40 and Robert Palmer cassettes were no substitute for the Led Zeppelin and Fugazi albums I discovered later on in life. But in hindsight, there was something very significant about UB40, especially during the Thatcherite years in-and-around Birmingham. The Birmingham of the 80s that I remember was very different to what it is now. Today, the city centre has become a cut-and-paste, cultureless waste zone of haphazard high-street phone shops, and chain clothing stores – of all your favourite sweatshop-made threads. The Birmingham I remember as a child was defined by the rich and colourful multi-culturalism of The Bull Centre, the food stores, cafes, restaurants, and record stores (which I didn’t go into). These conditions were ripe breeding grounds, creating fusion bands like The Beat, Dexy's, and of course, uniting the Campbell brothers to become the UK's biggest selling reggae band.

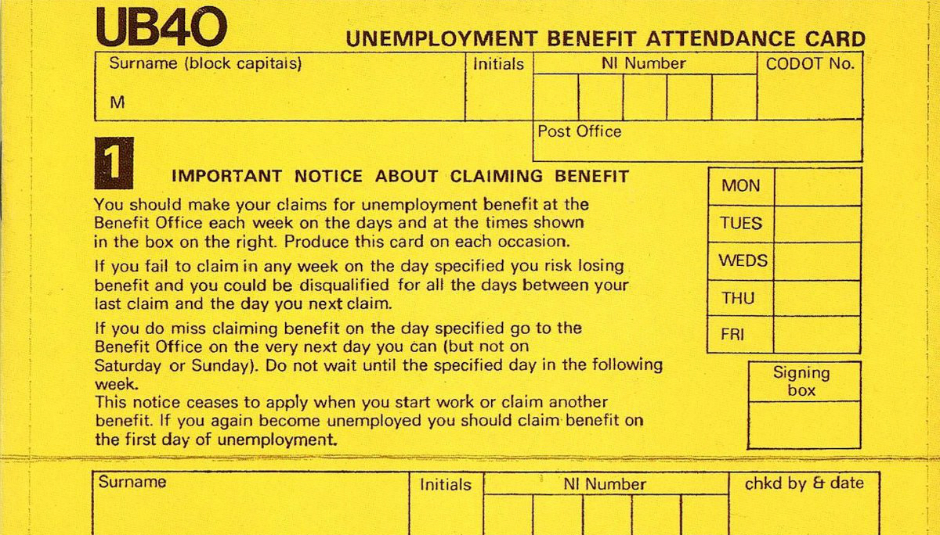

UB40's very name was taken from an unemployment declaration form, in itself an active statement against the Conservative government. The record sleeve, a copy of an unemployment benefits form. The LP’s title, Signing Off declared the band’s intent, distancing themselves from unemployment and benefits – a march to their own drum. “We don't need you anymore”, the band state. Not that they were wanted anyway. The LP was rife with political intent. 'Burden of Shame’ is still as relevant today as it was 40 years ago – a track about colonial guilt. Then there’s the powerful opener 'Tyler' – a song about an Afro-American who was wrongfully sentenced to jail for 41 years. And perhaps the best track UB40 have ever done, the slow-jamming of 'Food For Thought', whose lyrics deal with the hypocrisy of inequality and African starvation. So how did these guys ended up teaming up with The Mail on Sunday to give away one of their albums? How is it that Ali and Duncan Cambell, the band’s two lead talismans, fell out so bad that they both ended up fronting two separate UB40s and taking each other to court?

What I love most about Signing Off is the rudimentary simplistics of the melodies. It’s the sound of a ska-band finding their feet. There are the beginnings of an up-stroke played on the guitar, a bassline, a synth line, a lead, a drum-roll. And magic. The Specials encapsulated the sound of a post-urban Midlands, but there was too much macabre in their music. Too much skank. UB40 really encapsulated the zeitgeist and portrayed themselves as the heart-ridden realists of their time. The instrumentals on the album tell the tale of a band having fun with each other – a bunch of musicians from different backgrounds jamming to test their own limits, and the limits of appropriation. ‘12 Bar’ has a mix of soulful sax playing, dub guitars, drums, and an intrepidly naive bassline before Astro’s shout-outs take the lead. It’s hard to imagine how lead single 'Food for thought' — albeit being a great song — managed to make it to No.4 in the UK singles chart in 1980. This, coming from a rag-tag bunch of unemployed ex-carpenters and students, whose overall musical talents were just coming to light.

My love for UB40 returned after my move to Berlin. My first German teacher told me how one of his favourite albums was Signing Off, driven by the underlying political narrative, and dub instrumentality. Then, after helping a friend move house a few years back, the moving crew – a couple of older, larger, former East-German workers – began to detail their love for UB40 after I told them I was born in Birmingham. They saw them as working-class heroes, hard-working, Conservative-hating dub stars. It made me realise that I'd tried to distance myself from UB40, as I had physically distanced myself from the UK; from my life in the Midlands; from my mother's old cassette collection.

It also had a lot to do that UB40 had offered very little from Signing Off onwards. The Labour of Love collections are an offence to music, and their late 80s music sounds outdated. There was also Rat In The Kitchen. But going back to Signing Off, I can feel the warm, summer days of growing up in the Midlands. It felt like a time when anything musically could still happen (and it very much did). It was a time when ska and punk was over, and ingenious pop music dominated the radio and television. A moment before rap and hip-hop seeped into the mainstream. It felt like UB40, at the time, was something to stand by. If Birmingham had a soundtrack to the 80s, then this would be it.