Whatever your opinion of Laura Marling, she is an artist that attracts attention. The main talking point of Alas I Cannot Swim was the age of the artist, juxtaposed with the mature poise of the lyrics and music. Recorded whilst she was but 17, its ponderings on love and all that eventually garnered a Mercury nomination and high positions in those end of year lists. You probably know this.

You probably also know most of the indie tabloid gossip that is hard, so very hard, to remove from any appreciation of this record. For Laura Marling is going out with Mumford, out of Mumford & Sons. You may know this. You may not. And she used to go out with Charlie Fink, who produced her first record, Alas I Cannot Swim, and fronts Noah And The Whale. You may know this. You may not. And either way, you might not care, because you're either too distracted by the thought of an attractive, young woman making music to consider contemplating such ephemera (sigh), or you find all this gossip wearying and a fairground sideshow distraction from the music.

The problem is, as abhorrent as it is to discuss someone's lovelife in a music review, it has to at least be acknowledged, because relationships are important to the lyrical themes of I Speak Because I Can. There is a temptation to draw too much of a correlation between this record and Noah And The Whale's The First Days Of Spring (which documented the breakdown of Marling's relationship with Fink in a most public way) as both seem to deal with relationships in various stages of decay. Marling, however, is using characters to express herself, rather than writing directly. Songs are based on Penelope waiting for Odysseus to return, and wartime love letters. Given the shock she has expressed in interviews about the public dissection of the relationship, it's hardly surprising she chooses to veil her emotions. Lyrics like “And you did always say that one day I would suffer” on 'Blackberry Stone' and “I only believe true love is frail / And willing to break” on 'Goodbye England (Covered In Snow)' are only going to encourage these discussions.

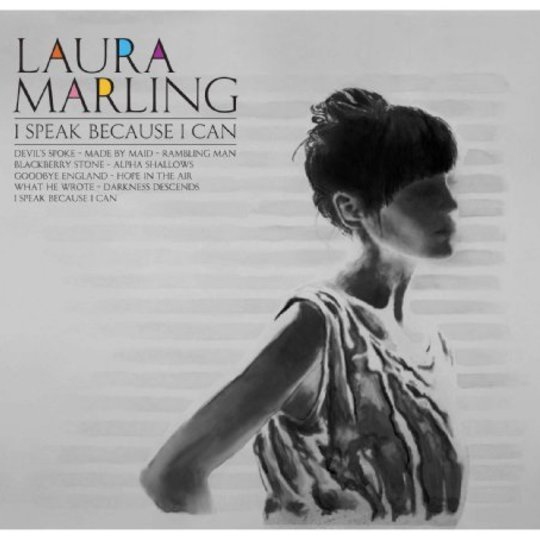

So now, having got these formalities out of the way, let us see to the music. This is what really matters. It has certainly advanced – the album, while still guitar based, makes greater use of dynamics, and utilises piano, banjo and strings to add to the sound. The primitive production of the previous record has been replaced by something more finessed, caused by the switch from Fink to Kings of Leon producer Ethan Johns. Marling's voice has developed over the last couple of years, becoming richer and deeper, as might be expected. It seems more self-assured too – the rapidfire verses remain, but there is more time devoted to holding notes, to letting them hang in the air. That slight nervousness has disappeared. As clear sign of this as any can be seen comparing the album titles – the defeatist sentiments of Alas I Cannot Swim, replaced by the defiance of I Speak Because I Can. This record, if anything, is a record of confidence. Marling would never have attempted the (successful) attempt at recreating the sound of the Russian steppes on 'Alpha Shallows.' The precocious maturity so noted on her debut has only grown. The incantations of first single 'Devil's Spoke' typify these gains. A drone leads into a churning acoustic line with real momentum to it, Marling raging over the layers of guitar and banjo which augment it. Despite these developments, it is still a record placed firmly within the folk genre. Witness the wandering tale of 'Made By Maid', with its “babe atop a log” which resembles Joni Mitchell by way of a childhood in the verdant English countryside.

Melancholy dominates on this record. Both music and lyrics are of a darker hue, bleaker. The title of 'Hope In The Air' is deceptive. The refrain of “No hope in the air / No hope in the water / Not even for me / Your last serving daughter” runs through the song, along with lines declaring “Why fear death / Be scared of living / Hearts are small / And ever thinning.” Often there is beauty to be found amongst the despair. A rare note of positivity can be heard on 'Goodbye England', with its accompaniment of flute and strings, as Marling expresses sentiments of wanting to be bought back to a snow covered isle, and to “lay here forever in the cold”, as well as some pro-feminist assertions in lines like “I tried to be a girl who likes to be used / I’m too good for that / There is a mind under this hat.”

And that mind, and this record, deserve to escape the back story and the tittle tattle, for I Speak Because I Can is an album of elegance and brilliance. Marling has developed from her debut, and her voice has grown both physically and lyrically. The songs are bathed in the folk traditions of England, and as such end up sounding timeless by proxy. Through Marling's unique touch they avoid sounding derivative, or tired. Side stories and back stories are just diversions from the real tale here – the age old bildungsroman of the artist turning into the master of their craft.

-

9James Lawrenson's Score