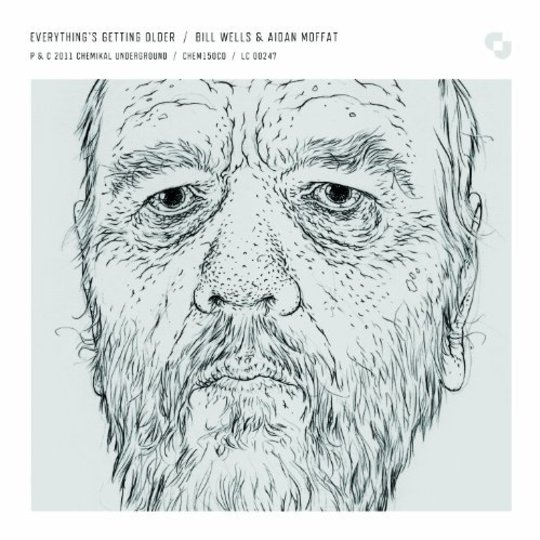

Seek out a physical copy of this album and the first thing you will be transfixed by, before even a note is played, is the deliberately distorted and mocked-up portraits of Bill Wells and Aidan Moffat (Assuming, of course, that the album proper will be a facsimile of the promotional copy. If not, the next few hundred words are a bit of a waste. If that’s the case, skip to the score or something, I dunno).

I’d guess that most album cover portraits are a carefully executed exercise in achieving, if not the most aesthetically flattering shot, then at least the one that most exactingly captures whatever image artists most want to project of themselves. Here, on this record sleeve, Wells and Moffat are old. Well old. Proper old. Old as hell. Old like milk that’s ignored its own use-by-date and decided to make the fridge its home. Old like an ancient pub dog that strains every sinew to make the daily excursion from bar to garden, and back again. Noses are tumescent and pockmarked. Ears hang, lips crack, eyes sag and hair creeps out at all angles in search of new territory to call its own. Obsessed with youth and vitality as we are, these faces are a nightmare. But there is something accepting, perhaps even defiant, about each look. ‘You’d better get used to it like we have, pal’, they say, ‘because stick around long enough and you will look like this. You will become this’, with some of the 12 tracks that follow Frank Quitely’s visual introduction almost acting as pieces of carefully whispered early-hours advice as to what we might expect to feel and experience on the way to becoming those grey portraits as time marches on.

Wells and Moffat first met when Wells was asked to play piano on Arab Strap’s Monday At The Hug & Pint in 2003. The pair, soon collaborating outside of Arab Strap material, completed ‘(If You) Keep Me In Your Heart’ in the same year and, not wanting to rush things through, took eight years to finish the remainder of the primarily piano-based album. Opening instrumental ‘Taosogare’ is a woozy closing time shuffle that sets the tone for an album full of the sort of encounters and glances towards the past or future that usually come after a hand has been curled around a glass or bottle.

‘Cages’ introduces one of the main themes of the album by wondering if a life free of responsibility can always be equated with personal freedom, or if growing away from a carefree youth with "hair of the dog and pills on Saturday, Sunday the same plus powders", into an adulthood full of "shopping lists and school runs, direct debits and tax credits" can brings its own unique senses of personal liberation.

‘Glasgow Jubilee’, unlike the many ballads here, drips with smut in its itchy, sweaty groove. Inspired by Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde, a play from 1900 that looked to scrutinize the sexual morals of the day, Moffat situates his line of lovers in modern Glasgow, purring "We could all be dead tomorrow, says the whore to the hero, and for handsome squaddies like yourself, my fee’s reduced to zero". According to Moffat, it was the moment of unabashed licentiousness that Wells was hoping would always appear on the album, and, with a line like "he pumps her in the car park, but no sooner has he spurt, than he says, I’m going back inside, the night’s still young for me", he couldn’t have wished for much more.

The album’s masterstroke, however, is the heartbreaking ‘The Copper Top’. With age comes decay, and with decay comes death. In ‘The Copper Top’ a man retreats to the pub after a funeral to be alone with his thoughts, so sick, as he is, of hearing everyone else’s memories of the recently deceased. Sitting in his fitted suit, only worn twice, he decides: "birth, love and death, the only reasons to get dressed up". Pint sunk, he leaves, glancing back at the copper roof of the pub as he leaves. Having oxidised over the years it’s now "a dull pastel grey’". "Everything’s getting older" he decides, before a mournful trumpet carries the rest of the song away.

By pure chance I come across a copy of D.H Lawrence’s Apocalypse soon after I begin listening to ‘Everything’s Getting Older’. It catches my attention because the front cover of this particular edition also has a decaying portrait of its author, in this case, a bust of Lawrence on his deathbed by Jo Davidson. Acting as a protest against the limitations of Christianity and rampant individuality, in this final work, Lawrence argued that man should seek to realign himself with the natural world and lead a more spiritual existence. He writes: ‘whatever the unborn and the dead may know, they cannot know the beauty, the marvel of being alive in the flesh. The dead may look after the afterwards. But the magnificent here and now of life in the flesh is ours, and ours only for a time. We ought to dance with rapture that we should be alive and in the flesh, and part of the living incarnate cosmos’. Wells and Moffat have created a stunning album that assures us of the death and decay that is to come, but equally, they tell us, as long as we are still around, there is life to be lived, and music like this to be heard.

The album’s penultimate track sees the birth of a child, with Moffat declaring, "All life is finite, so use your time wisely, look after your teeth… and remember, we invented love, and that’s the greatest story ever told".

-

9Michael Wheeler's Score