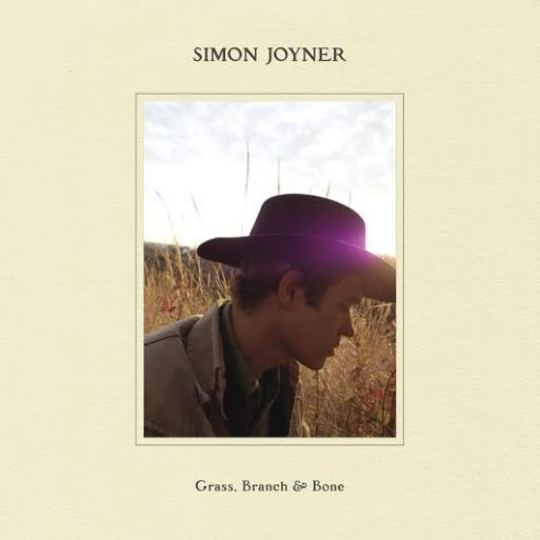

There’s probably no such thing as a bright and breezy Simon Joyner album, but Grass, Branch and Bone might be the closest we get to one.

Mind you, compared to its oppressive, hour and a half long predecessor Ghosts, almost anything would sound lighter. But this is undoubtedly one of the most carefree entries in Joyner’s discography. There’s very little in the way of his usual discordant electric guitar lines, battling against melody and groove at every turn. It’s a broadly easy listen. Nothing runs on for much more than five minutes, and everything basically stays within the recognisable parameters of ‘a song’.

Building up from a twitch of fingerpicked acoustic guitar, these tracks are decorated sparsely with pretty much just soft strings and wooden percussion. This is a much more a hollowed out, relaxed Joyner than we’re used to. Has he ever released something as fancy free as ‘Under My Skin’, for example? On most of his records, if he got someone under his skin he’d be trying to claw them out. Here he sounds pretty warm about it.

Even he – in his own voice – sounds mellower. Throughout his career, Joyner has (not unreasonably) been compared to talky songwriters like Leonard Cohen and Bill Callahan, combined with the early Nineties lo-fi of people like Will Oldham. He doesn’t so much sing as give a rough outline of what his melodies might sound like in the mouth of another. They’re both scratched out in sand and written in air – harsh and exact, but somehow infirm and blown about by his arrangements.

Grass, Branch and Bone finds him at his most tuneful in ages, despite how laboured he sometimes makes it sound. He can’t shake off the Cohen parallels, I’m afraid. Forced with an aching power, his nasal push of sustained notes recall the way Cohen reaches his way through the choruses of stuff like ‘Bird On a Wire’.

Thankfully, the effect here is similarly enrapturing. His vocal style has a starkly personal feel, and he has a knack for arrangements which extenuate this. On most of his records, his billowing, noise-laden landscapes leave him sounding abandoned at the centre. This time, the spacious textures give it a heavy intimacy.

Of course, it’s still Joyner, and it’s still packed with his slow tempos, slurred sadness, and dour imagery. The clue-is-in-the-title ‘In My Drinking Dream’ is loaded with some of the best examples. (“The sky is a bruise stretched over a broken bone”, is a choice favourite). But in spite of all of this, Grass, Branch and Bone stands as one of the easiest to inhabit of all of Joyner’s albums. Happily, it’s also as rewarding to explore as anything he’s done.

-

8Russell Warfield's Score