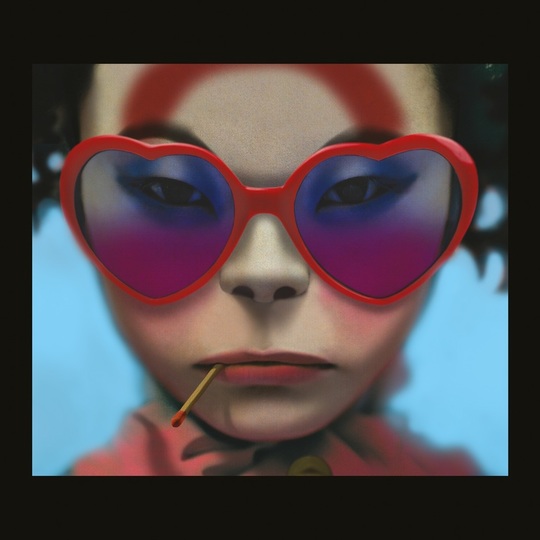

It’s easy to forget in 2017 just how dedicated Damon Albarn and Jamie Hewlett once were to the business of Gorillaz being a cartoon band. In the early days I believe they only did interviews in character – presumably over email – as their animated alter egos 2-D and Murdoc (plus Noodle and Russel, who were also them), and on their first tour the human musicians were never seen, concealed behind a screen on which their alternate versions were projected.

At the time this seemed like a slightly dickish but fairly acceptable thing to do, partly to differentiate the project from Albarn’s then still active other band (that’s Blur, btw), partly because British chart music was so boring in 2001 that a bunch of lairy toons were a blessed distraction. It’s also worth noting that it was easier to maintain the aesthetic charade of Gorillaz being a four-piece virtual band back when they had fewer people involved – their triple-platinum debut album only actually had two named guest performers on it, neither very famous, and there was no need to find a way of styling out having Bobby Womack or Sean Ryder on your song.

In 2017, 2-D et al still exist on some conceptual level – for starters Albarn clearly uses a different singing voice for Gorillaz to his other projects – but the days when journalists had to pretend to talk to drawings are long over. As such promotional interviews are now rather more illuminating, and it was interesting to read the band’s recent Stereogum chat_ and gain some insight into Albarn’s process – writing dozens of songs and reaching out to vast number of guests, shrugging and carrying on if they say no.

For fourth album proper Humanz, talks were held with Morrissey and Dionne Warwick, who said no in the end but might have completely changed the feel of the record if they’d been on it. Artists as popular as Carly Simon and Rag’N’Bone Man are relegated to the bonus tracks on the deluxe edition.

In a sense, Humanz is less an old-fashioned album, more a very expensive giant mixtape, a densely sparkling cloud of ideas and collaborative wish-fulfilments, loosely delineated by a bunch of skits, and bound by Albarn’s keyboards, shared session musicians (most notably souly backing vocalists) and more coherent production than many modern hip hop or pop records, with Albarn, The Twilight Tone and Remi Kabaka credited as producers of every song. It’s a more upbeat, party-orientated record than the dreamy Plastic Beach, and perhaps more so than before Gorillaz manage to pull off a balancing act between harking nostalgically back to a bygone era of vintage soul and clean, upbeat hip hop, and seeming entirely of the moment. They’re retro, but retro is big in the ago streaming, the house band for the current climate of everybody-likes-a-bit-of-everything, perma-shuffle hyperactivity, giving patronage to artists like Vince Staples or Popcaan who were born after Blur formed and would doubtless never get within earshot of that band’s white, middle-aged, British fanbase if it weren’t for this record.

Perhaps the sense of it being mixtape-like is compounded by the relative absence of Albarn-as-2-D. He’s still very much there, but there’s the sense that with each Gorillaz album that goes by he’s content to fade out of sight a little more: the band is so defined by collaboration that it’s easy to forget he was lead singer on ‘Clint Eastwood’, ‘Feel Good Inc’, ‘D.A.R.E.’, even ‘Stylo’, but increasingly he feels more like the curator than the singer: it’s not until track four, the swaggering trap of ‘Saturnz Barz’ that he makes a really meaningful vocal contribution, his wistful “I’m a debaser… I’m a heartbreaker” verse beautifully undercutting guest Popcaan’s autotuned bombast; you’re talking track ten (‘Andromeda’) before you can really say he’s on lead vocals.

It never feels incoherent, thanks to the constancy of the vintagey soul-plus-bloopy electro production/instrumentation, but Albarn’s self-relegation as lead singer has perhaps robbed it of genuinely great melodic pop moments (the closest being perhaps Patti Smith Group-ish closer ‘We Got the Power’, featuring Savages’ Jehnny Beth and – as has been widely noted – Noel Gallagher). There are some absolute bangers here, mind – the propulsive ‘Ascension’ (featuring Vince Staples) is a thing of metronomic wonder, like being zapped with a very pleasant machine gun, while the edgy sort-of-gospel of ‘Hallelujah Money’ (featuring Benjamin Clementine) is brilliantly awkward, knotty and political, a cold shower at the end of all the fun.

Humanz is good, because Gorillaz are good, and it distinguishes itself by probably being the band’s most party-orientated record, which is great. But ultimately it feel like Gorillaz are now more curators than provocateurs, locked into a classy, comfortable groove. We'll see them again next decade, no doubt, ageless as ever.

-

7Andrzej Lukowski's Score