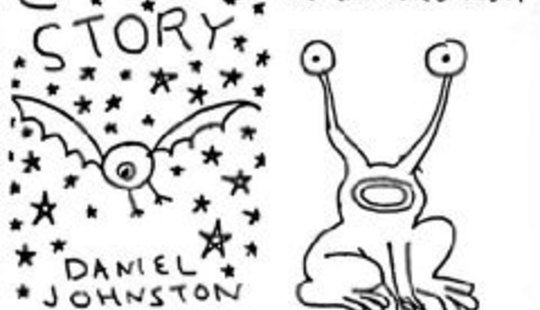

Pretend Everett True hasn’t been singing the praises of Daniel Johnston for 15 years. Pretend you’ve never heard the covers by 'alternative' acts on major labels asserting their integrity, and you can’t hear them in your head, alongside these stumbling, lisped, distorted originals. Pretend you know nothing about the relationship between Dada/surrealism and the art of the mentally ill, and just looking at the felt-tip cover-art DOESN’T throw up all kinds of questions about whether this is artistic expression at its purest… (Pretend there isn’t a problematic overlap between the projects of surrealists, psychiatrists, and outsider music fetishists: studying cultural forms that seem rudimentary, or damaged, to get at the hypothetical core of human nature.) Pretend it’s just music.

Yip/Jump Music (1983) is the fifth album by Daniel Johnston (then aged 22), and the first you’d listen to for reason of entertainment, more than the above. For better or for worse, it’s an Outsider Music classic. The percussion generally sounds like someone pounding meat, the guitar sounds like an elastic band being thrummed, and the chord organ either chugs or chirps or squelches, depending on its proximity to the microphone. (That’s a good thing: it’s amazing how much variation you can get, recording through a boombox; several songs seem to have been played with instruments made out of jelly.) Plus, there are all kinds of musical surprises that take some inventiveness when you don’t have many instruments, presets, or samples. There's the way ‘Chord Organ Blues’ ends, Hendrix-like, with a pair of chords you’d swear say “thank you” (or, “vvvang vyoo…”); the way the organ on ‘Almost Got Hit by a Truck’ answers the chorus (“oh, I’m so sad…”) with a mournful “oh-oh-oh…”; the way the organ counts down before Daniel’s trip on a rocket-ship.

As you’d expect, the lyrics to Yip/Jump are sweet, sentimental and fun, but they’re also self-aware and riddled with subtexts. The one thing they don’t do is refuse to feel, or pave over emotion with surreal imagery saying nothing… and this is where you start to see the appeal in the years when there’s still a 50:50 split between naïve tunes and weird rhythmic monologues; years before the collaborations with Jad Fair (of Half Japanese), and Mark Linkous (of Sparklehorse).

The reason so many songwriters in the Eighties and Ninties embraced Daniel Johnston is evident in the first few tracks: that he said a lot of things they were far too hip and self-conscious to say so plainly. Who else would admit to loving a band as obvious as The Beatles, and making music because they wanted to be the biggest band in the world? Who would admit to wanting to be John Lennon? “It sounds like a magical fairytale, but it’s true…” sings Johnston on ‘The Beatles’. Compare the layers of irony and bet-hedging in Thom Yorke’s spat-out delivery of “I wish it was the Sixties / I wish we could be happy / I wish / I wish / I wish that something would happen...” (he probably does, but he also wants to let you know, even at his most confessional, that he knows the Sixties was a lie sold by ad-men; sorry Thom…).

Also from Yip/Jump, the song Yo La Tengo famously chose to cover (‘Speeding Motorcycle’) manages to be a (CritSpeak Alert!) palimpsest of allusions to youth culture, with its own musician’s manifesto-as-hook: “we don’t need reason and we don’t need logic / cos we’ve got feeling, and we’re damn proud of it!”. Thing is, Johnston’s scared of motorcycles (and other rock’n’roll behaviour), and most indie musicians who aren’t hair-metallers probably are too; his charm is his candour about the fact. Ten years before ‘Loser’, and “teenage angst paid off well”, this is Daniel Johnston: “I’m a loner! I’m a sorry entertainer!” (accompanied by the sound of that elastic band being thrummed). This is the simple and direct side of Daniel Johnston… but he’s not an innocent, and when he analyses himself, or deconstructs popular culture, the reasons are complex (on later albums, he increasingly dissects his own self-mythologizing). Yes, his countless references to his own mental illness are attention-seeking… but he’s also a one-man Mad Pride. Yes, he knows that popular culture is founded on sex, and money, and selling ideas about love… but he’s not sneering at the emptiness of it all, or pretending you don’t know it too. (7)

Much the same could be said about the appeal of Hi, How Are You? (1983), paired here with Continued Story (The Unfinished Album) (1985); basically, the songwriting improves, and Johnston’s joined by some mates (aka Texas Instruments) who seem to be having a fun time down in the basement.

It’s at this point you can start to hear the Daniel Johnston whose fingerprints are all over the twee/lo-fi/ramshackle garage blues end of American alternative music for the next quarter-century. If someone tells you that Daniel Johnston is a big kid playing The White Album; that Half Japanese are a more rocking Daniel Johnston; that Moldy Peaches are an X-rated Daniel Johnston; that Jeffrey Lewis takes his similarities as far as making his cartoons an extension of the music… they’re talking about this period.

For those who know the records Jandek was releasing around the same time (i.e. fellow Texan recluse Sterling R Smith with his own enthusiastic but talent-shy friends), it’s a surprise how many parallels there are. Eerie monologues on chewed tape, riotous and mal-coordinated blues, obsessive hell-visions – it’s all here. It also turns out that there’s much more to Johnston’s influence on Sparklehorse than just that cover of ‘Hey Joe’ – there’s the androgynous voice set against a chugging chord-organ, and the samples of children’s records and farmyard sounds. (8)

For those of you not convinced you need quite so much, the compilation Welcome To My World’s been re-issued, too, pulling together the best of the material before MTV came a-knocking. Bear in mind, the four albums from 1980–1982 spring from Daniel’s late adolescence and focus on his unrequited love for 'Laurie' who married an undertaker, prompting one of the most idiosyncratic threads in his lyrics: the grim irony that he’d have to be dead to get her attention. (Ain’t that just what you need as a manic-depressive, to reinforce your complexes about sex and death…?) To end the long and tedious debate about whether it’s prurient to listen to music by the mentally ill: the answer is Yes: if you want Songs of Pain Volumes I & II you probably are prurient, masochistic, and holier-than-thou in trainspotter circles… but not if you come in a bit later.

Played alongside these early albums, Welcome to My World manages to be both representative and coherent, whilst prioritizing the stronger tunes. The opener, ‘Peek a Boo’, works as a kind of autobiography, updating us on Laurie. ‘Some Things Last a Long Time’ could almost be a Coldplay song (melancholy piano chords, wistful lyrics, harmonies and all) were it not for that astonishing guitar solo that leaves a shape on the mind’s eye like a bird splatting itself dead on your windscreen – and oh, No, it’s not dead, it’s still twitching, after the second verse.

In direct contrast, ‘Walking the Cow’ takes you to the other side of Johnston’s world; lolloping along merrily. As ever, there’s a lot more going on in these songs of apparent retreat from the adult world: in ‘Casper the Friendly Ghost’ not only does he slag off Casper, but he also seems to envy him returning from the grave, as if – Hey! Maybe that’s how to win Laurie’s heart! She who called him a 'pest' in ‘Man Obsessed’. Unsurprisingly, ‘Laurie’ the-actual-song is one of the prettiest, with a folksy feel to the bright guitar playing, and the jazzily demented piano behind that, like a rain-shower on a sunny day. Timelessly beautiful, but not in fact the best here, is ‘True Love Will Find You in the End’ (covered by Papa M, et al). For anyone who wants to get to the heart of faith as a consolation for the lovelorn, it’s all there in the lyrics: “this is a promise with a catch: true love is looking too, but it can only find you, if you step out into the light, the light…” No blind faith, no platitudes or delusions, no retreat from the world; just sincerity – as it should be. (9)