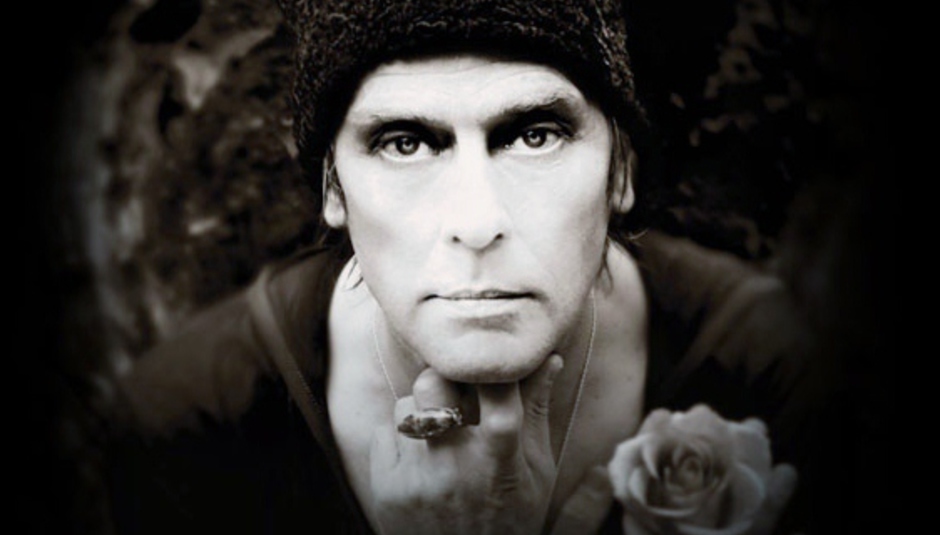

Having emerged from the tail end of punk rock's ethers in 1978 as lead vocalist with iconic four-piece Bauhaus, Peter Murphy has forged a reputation as one of the most unique, and challenging songwriters of his and every subsequent generation since.

Born in Northampton during the summer of 1957, his initial dalliances with Bauhaus saw him labelled "the Godfather of goth", somewhat unfairly considering the lifespan of the band didn't stretch beyond five years, bar 2005's short-lived reunion. Since then, he's worked with the late Mick Karn as one half of Dali's Car, while in the meantime carving out a solo career commencing in 1986 with Should The World Fail To Fall Apart, a record just as notable for its guest contributions from the likes of John McGeoch and Howard Hughes alongside Murphy's distinctive musings.

Now, fifteen years on, Murphy has recently issued his ninth album, ironically titled Ninth to a wave of critical acclaim, and with a European tour about to commence in October, DiS grabbed a recent rare opportunity to speak to the enigmatic singer/songwriter with both hands.

DiS: What are you up to at this present moment in time?

Peter Murphy: I'm getting ready for an American tour at the moment. It's a double headliner with a band called She Wants Revenge. I've also recently sent a letter to Axl Rose asking him if he wants to work with me. In the 1980s he wore one of my t-shirts during an interview, plus I'd like to reach that audience. In a couple of days I'm heading off to Istanbul to mix some live tracks that will form an EP that's coming out soon. The EP's called The Secret Bees Of Ninth. They're not so much outtakes, but songs that were more epic than the majority of Ninth, in a similar vein to 'Creme De La Creme', which is the last song on the album. I decided not to put them on the album as it would have sent the record out of kilter in a way. I'm also talking to some film producers both here in L.A. and back home in Turkey for possible acting parts.

DiS: I read somewhere that you'd been approached to play a part in a new adaptation of 'The Young Picasso'.

PM: Well not approached as such. The way it works is that you tend to meet people, and the director came to see me. They've got a whole host of other considerations for the role besides me, but I get on well with that particular producer and she has a gap which she believes I could fill. It's also a question of whether they can raise enough money to make the project viable; the last I heard it was still on, so it's just a case of waiting to see if I'm cast. It's certainly one film I'd love to be involved with.

DiS: Do you see yourself as being more involved with acting and drama rather than music these days, or do you feel the two have always run parallel with each other?

PM: It was always mixed. What I do as a vocalist - I came into music as a raw untrained musician with just my voice and my words. I came into it believing that I was already there, which was probably a bit too over-confident. I think acting and opening the creative senses is all about uncertainty with a mix of narcissism and a need to express. I think I could walk onto any set as I have done in the past and everything would be absolutely fine. It isn't that different to walking onto a stage, so from that angle I don't really see the two as being completely separate. With music, I always felt that the band were the back-up for what I was doing. Not a back-up band, but more that the music was an excuse for me to get out and perform. That's why the cover of Ninth has got me portrayed like a mystic fool. Or a magician, a jester even. The King Of Goth who's not a goth! It's very theatrical in a way yet also very raw.

DiS: How do respond to being labelled "The King Of Goth" and other such titles associated with that scene?

PM: I don't mind those kind of labels because that's the reality of it, they're bound to typecast you. As long as they're talking about you that's fine because once they get in the door, I'll sort them out!

DiS: It's not strictly true though is it in a pedantic sense, as Bauhaus had already been and gone by the time the whole Goth phenomenon blew up.

PM: You're right, although I do think there is a validity to it. But, it has to be looked at from the root rather than present day definition. I would say the whole Gothic culture is very significant. It's totally unique, and it embodies and holds more than just music. It reaches into fine art, poetry, painting, theatre, all sorts of elements from the ground up. I liken it from a musical point view to that of a punk who's becoming more self-aware; wiping snot off his nose and dressing up a bit!

DiS: It was a very original sound at the time though wasn't it?

PM: Bauhaus were a bit like that....We came out at a time when everyone was navel-gazing just after punk. No image, no ego. The Cure were like that as well, then suddenly there was this black high hair and really badly applied make-up! But that's OK. It's very British isn't it? We were very radical in that sense. We came and said we're beautiful, we're male and we're very dangerous. Where you get John Lydon's rants, which to me were very irrelevant even back then, Bauhaus weren't anti anything. We were about celebrating both the beauty and the ugly in a not obviously beautiful sense. That is quintessentially a Gothic notion. The original Gothic notion wasn't just about architecture it was about finding beauty or transcendence in the most unlikely places. Even looking at Gothic architecture itself it's quite spinal...

DiS: When I listen back to a lot of Bauhaus songs, pieces like 'Stigmata Martyr', 'Bela Lugosi's Dead' or 'Rosegarden Funeral Of Sores' they still sound like nothing else on earth, even now, so heaven knows what it must have sounded like in 1979!

PM: That's how we felt at the time, and that's how I still look upon those songs. That kind of injection of light crackle into what you do. It's unpredictable even though you have the shape of a song, but when you get on stage and perform it has to be about what happens in that exact moment. It's not about sitting on your laurels and being cats saying "We've got a name now, come and like it". Every audience is important and often the best audiences are those that don't really know you. They're the people you've really got to work hard with. It's pure rock and roll, in the same as Led Zeppelin or The Doors are considered as being. I'm one of those. It's not like I'm bragging but I genuinely see myself as being a performer in the same vein as Frank Sinatra or Muhammad Ali or Mick Jagger. I'm not like them but I am of that type, if you know what I mean.

DiS: You've been based in Turkey for a number of years now. What is it about the country and its people and culture that first attracted you and subsequently made you stay there for so long?

PM: Well practically speaking I married a Turkish lady (Beyhan) in 1982. She's a choreographer and also the artistic director of the National Modern Dance Company here in Turkey and has been for many years. I always found London to be very isolating and I'm a very reclusive person... I like to keep my head down. I don't like to be the social commentator, I prefer being almost invisible. I think that's when I've created my best musical work, the times when I've not given everything away and left a few blanks here and there instead. People fill them in, and that's part of the enjoyment with the style of writing I choose to engage in. With London, I think to myself "Why would I want to spend £5 on a cup of tea?" When I started coming to Turkey I found it a very social culture, very hospitable and warm, very family orientated and I thought it was a perfect place to raise our children. People are also very musical here. If one person starts up a song, everybody knows it and sings along. It's a very musical culture. You can walk down any road at any time and always hear music playing. I've learnt a hell of a lot through living here, most of it remotely. I genuinely think it's a good thing to live outside of your comfort zone because I believe that builds character.

DiS: I guess the longer you spend there it kind of becomes your comfort zone doesn't it?

PM: No, you're absolutely right. But, even though I live here, I'm all over the world most of the time recording or touring. I've only recently found a studio in Istanbul which I really love, which will be the first time I've seriously worked here. I'm also quite Americanised in a sense. I have a deep love of America, almost like a fascination with it. A bit like any Brit really. It seems like a mono culture but you find out it's not when you travel around. Cultures change from state to state and city to city. It's not that different to Britain in many ways; three miles down the road someone might speak in a completely different accent or adopt slightly different attitudes.

DiS: Would you ever consider returning to the UK?

PM: Not living there, no. I can't see myself moving back to the UK permanently. I was recording over there last winter in Oxford for three months, and it was great, but I'm less attracted to this kind of inverted interior attitude which comes across as being very repressed, willfully ignorant even. When there is intelligence it's put across in a way that makes it feel owned, do you know what I mean? You have to make appointments to visit your friends. All that kind of stuff really gets to me. And the bus drivers are all miserable bastards! England is like an old, miserable spinster. I tried to get a train up to Scotland from Oxford but it was just ridiculous. In America you turn up to a station on the day and board a train for your destination. Not here though, everything has to be booked in advance or it's a case of changing several times and in some cases, having to wait until the following day. Not so much "No Can Do" but more a case of "Can Do But Would Rather Not". I'm a Brit who knows my country only too well. I love coming over every so often to visit, but by the time I leave, I thank my lucky stars that I don't have to live there.

DiS: Do you keep in touch with what's happening musically over here?

PM: Not so much in Europe, no. Most of the time I tend to let things arrive on my doorstep. There's so much music being made now I just keep an open view. I thought Amy Winehouse was the epitome of what a genuine rock and roll performer was all about. No Hollywood, no effort, no million dollar videos to pump it all up, no hype. She just walked out, opened her mouth, and that was it, job done. That's where it's at. She wasn't interested in fame or all of the bollocks that goes with it. It hit me quite hard when she died, even though I never really knew her.

DiS: It's fair to say you've influenced several generations of artists since putting out the first Bauhaus record in 1979. Did you expect to be held in such high regard at the time, not to mention ever envisage that people would be sat here talking to you about your lifetime in music thirty-two years later?

PM: I kind of expected it without meaning to sound big-headed. It's like when we were talking about Amy Winehouse earlier, I understand the fame aspect and that's where a lot of irony comes in, and I embrace it in a way that also tries to remain creatively smart with it. In all humility, I'm not surprised as if I were a fan and not me I'd want to go to as many of my shows as possible or listen to my music every five seconds. That's how every musician feels about themselves. You go through periods where you're tested as well. The break-up of bands, lack of a label or funding, there are lean periods. At the same time, I don't see myself as the kind of artist that's limited to a fashion or time. I think I'm always kind of renewing myself in a way. What also helps is that I'm not just some tired old studio musician. Playing live is just as, if not more, important to me, and as a result the audiences will always recognise something. I'll take as much criticism as is out there. I really don't mind. I'm like a whale or a dolphin; I don't mind swimming under the surface while all the loudmouths have their twenty-one minutes - I think it is twenty-one rather than fifteen now in this age of entitlement - of fame. It's almost like saying "You get on with it and I'll do the business".

DiS: Ninth is your first solo album for seven years since 2004's Unshattered. Why the long break between records and what rekindled your enthusiasm to make this album?

PM: Well actually, Go Away White, the Bauhaus comeback album from 2008 I'm claiming is mine as I pretty wrote it myself. That's a whole load of energy that I put out for the other guys and wanted to make that work, so there's a whole three-year period where I was purely writing songs for Bauhaus.

DiS: So you're claiming Go Away White as your own rather than a four-way collaboration?

PM: Well, not totally mine. It was a collaboration but it was more about it clicking towards the last third of it. Remember, we went in without anything. It was a typically conscious decision to start from scratch without any material and record and mix it all at the same time. We'd just finished touring with Nine Inch Nails and we spent eighteen full days in the studio straight after. I was writing much more than I would normally when it comes to music. It is still a Bauhaus album though. I think the heart of the band is Daniel (Ash) and I in a way. Kevin (Haskins) and David (Jay) are very crucial of course as a rhythm section, and there are roles which we all slipped into but there's a lot of baggage, not only from the early Bauhaus years but also from the other band that the other three did throughout, Love And Rockets. You know, there's a whole agenda going on there that I wasn't aware of. So I think we really started to click and I remember Daniel saying "Now we're getting there!" towards the end and looking back, when it clicked we always worked fast and furiously. That album is a great statement once you understand the perspective that it was almost created immediately. There was no planning, no pre-writing, it was all very spontaneous. Then again, it was left unfinished. That's why the final mixes are actually the rough desk mixes, because we pretty much called it a day straight after that. Eight months of touring, writing and recording took its toll, which is very frustrating.

DiS: Do you ever see yourself working with the other three guys from Bauhaus again?

PM: Not anymore, no. I was the one who really held out and abdicated. I genuinely believed we had a lot more to give at that time, and in some ways still do. But, having worked with those guys again, there was a miserable British insulation anyway within the band. We were scared of even talking to each other. We were very repressed and uptight. I don't think we're relevant as a band anymore, actually.

DiS: I'm quite surprised you say that...?

PM: I'm relevant, but Bauhaus aren't. Maybe we could still make some good music together, but we couldn't have made a Ninth. That's how Ninth came about in a way, sort of like the after trail of that energy that was still left up in the air in a way. Rather than wait around for them to do it, I did it myself.

DiS: It's interesting you say that because some of the lyrics seem quite personal while referencing individual members of Bauhaus. 'I Spit Roses' for example states "The captain is sea, in the moonlight the fame, reflex us and him. He blurts karma, no sin, the tall one, astute; the ginger all things to all men...." while 'Uneven And Brittle' declares "I get crushed by my dreams, that I clawed and begged for. It's myself I deceive, I got all I asked for".

PM: 'I Spit Roses' is a direct reference that kind of sums up the essence of what always split up that band. I was sick of being asked why did Bauhaus split up so I thought, "Right, I'll write a song about it and tell them." In a way, it's a very Bauhaus notion that whole song. 'Uneven And Brittle' wasn't sourced in that experience but I can see that it's related to that. I do try to be spontaneous rather than anal, very intuitive and give it everything I've got when writing. Everything, unconditionally, to the point where I'm aware that I'm actually offering myself to people free of charge. But then I would get very disappointed when that same level of commitment wasn't forthcoming from others. I guess it's very naive to expect that, especially from people I'd worked with in such a wonderfully heroic experience. Then all of a sudden I thought, "Wait a minute. These people have no idea what's going on". Then I started to understand it was my quality and therefore wrong to expect it of others. So yes, I do get crushed by my dreams, but I'll still dream...It's a less gay version of Elton John's 'I'm Still Standing', but I'm totally straight and scary, and I wear make-up and look gorgeous!

DiS: I guess the image Bauhaus flaunted in 1979 must have raised a few eyebrows back then?

PM: Totally! We'd get comments like "What are these people wearing?" They used to accuse me of pretending to be David Bowie but I wasn't pretending; I was more like what he should be. The whole strutting...it was very real. The music press at the time really didn't get us at all. They tried to squeeze us down, destroy us even, which was great because it brought more attention our way. It didn't need a Malcolm McLaren to hype up some notion of anti-something or construct an attitude. We came along and really did make it by ourselves. Record labels chased us, not the other way round.

DiS: Bearing in mind you received little to no radio airplay and there was no Internet to spread the word around, it must have been very organic in a word-of-mouth sense?

PM: Totally! It was brilliant, and that's what all of us really experienced. It validated my "I'm already there" notion. I don't think that's recognised enough when people talk about Bauhaus. We did exactly what we wanted.

DiS: You're working with a guy called David Baron on Ninth, whose production work isn't that well-known outside of his native Woodstock. How did this collaboration come about and what did he bring to the sessions?

PM: I met David through an artist who supported me in 2005 called Sarah Fimm. She's a really talented independent female artist who also lives in Woodstock. She invited me over to work on a couple of songs, and the studio she was using (Edison) was owned by a partnership between Lenny Kravitz and David Baron. David is more of a backroom person, but just watching him work with Sarah made my intuition tell me "There's the guy for my next record". Up to that point I didn't even know of him, yet he's very objective and extremely knowledgeable when it comes to music. He knows who The Residents are, he knew everything that Bauhaus did, seemed very clued up about the English music scene as a whole in 1979, almost as a sense of culture. That's what first attracted me to him, and as a result I felt that he could be trusted towards our sensibility. Plus he has this box of telephone-line like plug-in analog processers, which I found quite fascinating. Once you plug one in you'll get a certain sound, and if you move an inch you'll lose that sound. He's also a very good musician, and he's not a geek either, so I started to hang out with him in Woodstock and ended up living there for three months. We became really good friends, not only me and David, but also with his wife and children. Sarah Fimm would also be there, and it was quite refreshing watching these young American independent artists that don't quite really get the British indie attitude in that while they were absorbing all the influences they actually turned out something that was remarkably new and awkward. Another thing which I liked about David was the speed of which he worked; I like to record quite quickly. The album ended up being recorded in seven days and then the whole mixing and mastering process was completed over the next two to three weeks.

DiS: Ninth is a very diverse collection of songs, almost impossible to categorise by genre in fact.

PM: David and I would sculpt ideas and everything was brought to the table, all written and arranged yet still fluid and open. We decided to really try and capture the band that I'd been working with live for the past seven years. Rather than hire a bunch of so-called names who'd bugger off halfway through to do other projects, I wanted my band to have their own input with this record. It was pretty much a case of me throwing them in a room and saying "Here are the materials, build me a house!" When you commit to people they'll show some commitment in return. That's what I'm like, very full of uncertainty and if it's wrong I'll say "That's OK, it'll be right in a minute". We added another guitarist, John Andrews, who's from New York and really quite brilliant. We'd capture each performance and I sang live on every take. I'd like to think I engineered a community between everyone that was present, which for me makes such a difference to digitally sending pre-recorded files over the internet as so many artists do these days.

DiS: I guess it's difficult to call something a collaboration in the truest sense of the word when that happens.

PM: It's just music by email. I'd put a lot of what we had down to good preparation, and also having a lot of the material there, ready. I'd like to think myself and David have enough talent between us not to worry about maybe having to hire Brian Eno in, you know what I mean?!?

DiS: Brian Eno's a name that's always been linked with you back to your Bauhaus days and the 'Third Uncle' cover on the b-side to 'Ziggy Stardust'.

PM: Oh, always, and also the ambient records as well, you know classics like Taking Tiger Mountain and Green World. In fact, when I was thinking about producers for my Love Hysteria album in 1988, I dropped some demos round to his Opal offices and really wanted him to do it. This was before The Joshua Tree, and I remember his people at the time saying he wasn't interested in making music any more so probably wouldn't even bother to listen to it. Then I called back a few days later and was told that he'd listened to them and found them "Nice", which I thought was great and very exciting, but also that he was still no longer interested in making music. Eight months later, Bono must have flown over his house and dropped a few sacks of dollars on his doorstep for him to produce The Joshua Tree and the rest, as they say, is history.

DiS: I also see long time associate and collaborator Paul Statham, formerly of B-Movie and songwriter for people like The Saturdays in recent years co-wrote 'Never Fall Out' on the album.

PM: Yeah, Paul's great. We sort of parted company when he started working with Pascal Gabriel after the Cascade album in 1995. He's a very talented songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who works at an unbelievably fast pace and I think he found his niche when he started writing and producing for a lot of pop acts. He's very prolific in what he does. He'll give me all these unfocused sketches and I'll then try and shape them into songs. What he would offer me were always very interesting tangents. We're always in touch and I'll always ask him to send me over anything he's got when I'm making a record, and 'Never Fall Out' was one of those I liked a lot which is why it ended up on Ninth. It's really quite transformed as all songs do from the original but I'll always give credit where it's due and without Paul (Statham) that song would never have materialised.

DiS: Moving onto your work with the late Mick Karn in Dali's Car, I believe you'd been working together on an EP towards the back end of last year? Are you planning to release all the songs which were finished and if so, when will they see the light of day?

PM: My whole gesture was a very pastoral one to Mick. I hadn't seen him for ages and then I heard he was seriously ill in June of last year. I was sat here wondering what I could do for him because we'd made a whole album together, so we got back in contact with each other via email and I asked him whether he was well enough to work, and if so, why don't we make another Dali's Car album? I'll raise the funds and organise it all, you just get writing, and he was so happy. So anyway, I raised enough money to get us ten days in a studio in Oxford, and he came down with his wife and child, and we made as much music as we possibly could. Unfortunately, Mick had a relapse after the first night so I wrote furiously for the rest of that week whilst still trying to help Mick out and we ended up with five songs. In the ensuing months, Mick was going to put together some more fragments but he was really too ill to continue. As a result, Steve Jansen, who used to be the drummer in Japan and a guy called Jacko, one of Mick's old friends, laid down some drums and extra guitars, so we ended up with this beautiful EP. Everything's now with Mick's family's accountants, because all proceeds are going to benefits for them, but in terms of a release date we're hoping to have it ready for October 24th or as near to that date as possible. I'm just proud to have been the last person to work with Mick. The whole project was really poignant because we split up in 1984 on not very good terms. He'd just come out of Japan and I'd just finished with Bauhaus, and relationships in our previous bands had ended badly so neither of us found it easy working together back then.

DiS: You're touring throughout October including five UK dates. What can we expect from the live shows and will you be playing material from all stages of your career including Bauhaus and Dali's Car?

PM: Previously I would never contemplate playing Bauhaus songs during my own solo shows, but now that band is over I have started to incorporate some Bauhaus material into the set. I think the Bauhaus flag's been handed over to me lock, stock and barrel. I've given the others a chance to really make a commitment which didn't happen, so as far as I'm concerned I can draw off all the Bauhaus catalogue. I'm going to be playing songs off Ninth of course and other pieces from my own back catalogue. With Dali's Car it will be difficult at this stage, obviously with Mick's passing as well, but I am planning to gather a couple of musicians to do specific Dali's Car shows. It's all very tentative in my head at the moment.

DiS: Is there any of your solo material which you wouldn't consider playing live, or would maybe even struggle to incorporate into the set at this moment in time?

PM: It depends onthe kind of set that I'm doing and the context of the show, and also the time. At one time I'd never touch the Bauhaus stuff because I didn't want to come across like Robert Plant playing Led Zeppelin songs. Over time, I've realised that my current band, particularly our guitarist Mark Thwaite, can really play those songs as good if not better than the guys in Bauhaus did. I think people do want to hear it but if I do it, there has to be an edge. It can't be about mere reminiscence. Now I'm free of Bauhaus it's a really great feeling because I do own those songs. I'm listening to a lot of my earlier solo albums again too, which means I have to tread carefully in terms of being too retrospective. I'm not a retrospective artist, but then at the same time, there are older songs that people do want to hear. It's like when I saw Lou Reed play once, and he played a set consisting almost entirely of new material, which was fine but I still wanted to hear 'Satellite Of Love' and 'Vicious' so in a way it was quite disappointing too. I'll also try and get a feel for what the audience wants early on, and if necessary change the set live while we're on stage.

DiS: Really? What do your band make of that?

PM: They're fine with it. We're so well rehearsed that I could call a song at any time and they'd play it, straight away. I start to scare them now when I plug in the electric guitar myself and play on songs like 'Stigmata Martyr' and 'Dark Entries'.

DiS: You've already mentioned the songs which didn't make Ninth that will form The Secret Bees... EP. Are there any other plans in place for the follow-up to Ninth, and if so, when would you be hoping to release it?

PM: I've got loads of songs that are ready to go. I'm actually talking to both David (Baron) and another producer at this moment in time. I really want to tour Ninth for the time being because I genuinely believe in it so much. It's important this album gets heard so I'm going to work it as much as possible. I would like to go into the studio right now in between shows but that's not really cost effective.

DiS: It's probably not good for your health either...

PM: Yeah but I'm half-Irish which makes me slightly mad! My dad was an iron worker who'd work double shifts in the week then have a window cleaning round at the weekend. I guess that whole work ethic is in the blood? It's been much harder work bringing up two children to be honest, but worth it all the same. I think touring actually keeps you physically well, provided you stay away from the drugs and booze of course.

DiS: Finally, bearing in mind the present state of the music industry, do you think if Bauhaus were a new band starting out today they'd be able to survive and prosper or enjoy the longevity that you have thirty years down the line?

PM: The game is always about fame but the doorways get painted iin different colours. Regardless of the industry, there are still three basics which every band needs to master; their music, their recordings, and their performance. I mean, there's so much more accessibility to an audience now than there was in 1979, and while there's always the danger of saturation, the cream always rises to the top.

Peter Murphy is on tour throughout October, November and early December including the following UK dates:-

October

12 London The Garage

13 Bristol Academy 2

14 Glasgow King Tuts

15 Leeds Cockpit

16 Liverpool Academy 2

For more information visit his official website