“Because when you were 19, didn’t YOU ever want to create something beautiful and pure just so one day you could set it on fire and watch the city light up as it burns?”

Well, didn’t you?

As an epitaph that might sound melodramatic, but it neatly sums up the rise and fall of Sarah Records, one of the UK’s most underrated labels from a time when “indie” was still an ideology and not a genre. Set up by Clare Wadd and Matt Haynes in 1987, and operating out of a telephone-free basement flat, the label released a hundred 7” pop singles over eight years, before throwing a big party and closing down; a somewhat inglorious end to an institution that was passionately, if not widely, loved.

The Field Mice, Heavenly, Blueboy, Another Sunny Day; the list of talented and influential bands who called Sarah Records home is long and distinguished. Many of the groups were ground-breaking in their own way – Blueboy’s Keith Girdler was one of the few indie singers to address gay rights in his lyrics – and what was, at the time, airily dismissed as “twee” and “fey” by some of the more sexist, Neanderthal elements of the music press has been since been critically re-appraised; putting Sarah at number two in their list of the Greatest Indie Labels of all Time, the NME praised their roster for sharing “a knack for wide-eyed melodic vulnerability”.

That’s quite a turnaround from a publication that once infamously reviewed a Secret Shine single thus: “This isn’t music, this is cancer”. Then again, Wadd and Haynes were often in open conflict with the boozed up, beer’n’lads brigade that wrote professionally about music in the early 1990’s – a time when Britpop was beginning its rise as a cultural juggernaut. “Presumably, they were terrified of having their masculinity called into question,” says Haynes now. “Music was for boys, and the only women who were allowed to play were those who were lauded for rocking just as hard as the men, or who fitted some singer-songwritery notion of femininity.”

Despite folding twenty years ago, Sarah Records has been kept alive in spirit by hardcore fans in love with music that remains simply too good to be allowed to disappear in the fog of time. Listening back to some of the releases, it’s remarkable just how prescient it all was; the dark, swirling post-punk of The Wake, the shimmering guitar-pop of Heavenly, or the gorgeous, dreamy epicness of perhaps the best known band of the Sarah stable, The Field Mice.

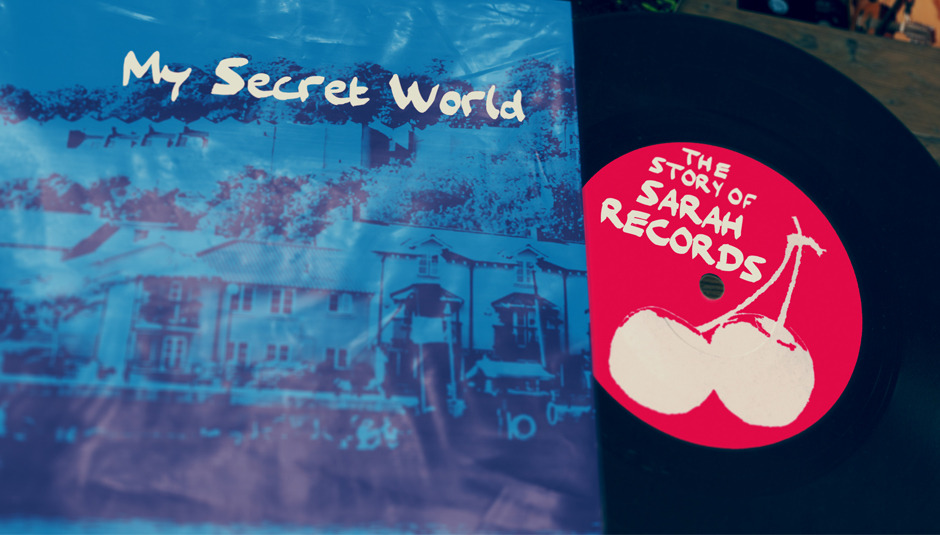

Time for a critical re-appraisal then, something that film-maker Lucy Dawkins thought was well over due. As an avowed music fanatic, and someone whose teenage years were dominated by fanzines and flexidiscs and afternoons spent “mooching around record shops”, Sarah Records provided the perfect subject for her final year University project. The result – My Secret World – is a lovingly crafted homage to the label and the bands that left such a lasting legacy, complete with extensive interviews and contributions from Wadd and Haynes themselves. Digging deep in to the ethos and foundations of the people that made Sarah what is was, it perfectly captures the spirit – and hope – of the times, and perhaps most importantly, places the actual music front and centre. I spoke with both Wadd and Haynes, and Dawkins, about feelings of nostalgia, Sarah’s legacy, and why they are happy to leave the label in the past.

My Secret World. The Story Of Sarah Records. Trailer 2014 from Yes Please Productions on Vimeo.

Lucy Dawkins

DiS: What is your personal history with the label, and how did you come by it originally?

Lucy Dawkins: I moved from Kent to small town near Bristol (Clevedon) when I was 12, because my Dad changed jobs. I spent most of my time on my own and would travel into Bristol every Saturday and mooch around the record shops. I was already into The Smiths, Mighty Lemon Drops, We've Got A Fuzzbox, the usual 'gateway indie bands'. From listening to Janice Long and John Peel I became interested in a wider range of music, and I just stumbled across Matt's Are You Scared To Get Happy? fanzines and Sha-la-la flexi discs in Revolver Records one day. They were cheap, which was important because I only had pocket money to spend, and the fanzines that accompanied the flexi's were a big draw because usually I only had record sleeves and liner notes to pour over, and there's only so much information you could gather from them. Matt's fanzines were funny, surreal and opinionated. I was pretty bored and isolated living in Clevedon, and I was too young to go to gigs, so it was really fascinating to enter into this new world through his writing. Through those I discovered the 'fanzine network' and started to write and receive letters and music from people in such far flung and exotic places like Glasgow! Pre-internet, as discussed in the film, fanzines, flexis and homemade tapes were only way to listen to music that was too obscure for the music papers to cover, or even for John Peel to play. I bought all the Sha-la-la flexis (bar the Siddleys one for some reason), then when Sarah started I bought Sarah 3, 4, 5 and 7 and then the Shadow Factory compilation. I continued to buy Sarah's releases and wrote to Harvey Williams for a short while when he lived in Penzance, and received a home recorded tape of his stuff.

What was your gateway into the label i.e. which artist or artists were you most interested in on their roster?

The Shadow Factory compilation is just fantastic! It totally encapsulates that time and it stills sounds great today – as do most of Sarah's releases. I particularly liked The Orchids, 14 Iced Bears, Field Mice and The Sea Urchins at the time. The stuff they released later on is great in a different way – Blueboy, East River Pipe, and Even As We Speak in particular, all really solid and accomplished pop music. I just can't understand why stations like 6 Music haven't picked up on it yet. I think if a lot of this music was released today it would be huge!

Were you one of those super fans, who bought everything they put out? Or more a casual fan?

I've never had a collector mentality, but was completely obsessed with music of all genres. There was so much going on then – Riot Grrrl, the whole Olympian K Records scene, Shimmy Disc, Sub Pop, Matador, 4AD…and I was discovering all the great music from the 60s, 70s and 80s. Then in the 90s I really got into electronic and dance music. I was living in Sheffield and, being the home of Warp Records, completely immersed myself in that scene for a while. So with so much music to consume I guess I was more of a casual fan compared to the Sarah completists!

What led you to think about making the documentary, and to put the wheels in motion and contact Clare and Matt?

I had worked as a graphic designer for about 10 years but was no longer enjoying it, so I returned to full time education to study filmmaking – something I had always been interested in but had never done anything about. For my final year project I knew I wanted to make a documentary, and still being pretty obsessed with music, wanted it to be music related. Living in Bristol, and with my early attachment to the label, Sarah seemed like the obvious choice. I felt the label didn't command as much respect as it should – it had kind of been hijacked by a scene that I think did it a great disservice. There was a lot of very talented songwriters and musicians on the label and to term Sarah's whole discography as 'twee pop' is criminally unfair. Clare and Matt's politics had also been forgotten, which was at the root of the label. I got in contact with Matt via his 'Smoke' website and expected him and Clare to completely reject my idea of making a documentary – for one thing I was a final year student. But I went to see them, we had a few drinks, and I convinced them that I had their best interests at heart. I have a great deal of respect for Clare and Matt and I think it says a lot about them that they trusted me to tell their story. I was a final year student, a 'mature one', but still inexperienced in feature length documentary making. They encouraged and supported me just as they had all the bands they signed to Sarah

Why do you think Clare and Matt were so receptive to the idea?

Probably best to ask Clare and Matt! Maybe like me, they felt the label had become misunderstood and saw this as an opportunity to tell their side of the story. They were very keen on getting the political and feminist aspects of the label across, which I was too. When I first met them, I had just created a radio programme about the Bristol Feminist Network and their campaigning work. I think they understood right away that I was coming at it from the right angle. I would like to make it clear that whilst they were very helpful and encouraging, they also kept their distance and didn't interfere in any way. They only saw the completed film for the first time a couple of days before the preview screening in Bristol.

How easy was it track down all the various band members and convince them to appear? Was there anybody you couldn't find, or who refused to take part?

It was pretty easy to find most people via social media. Can anybody truly disappear these days? Because I was relatively inexperienced, having only directed a few music videos, I think a few people didn't take me that seriously. It was hard work actually arranging an interview date with some, even if they seemed agreeable to the idea. I was also funding the documentary myself and when I started, I’d also just co-formed a film production company. Arranging shoots in other cities works out really expensive with travel and accommodation etc, even with a crew of just two people, and some people I just couldn't film due to budget restraints. Bobby Wratten flat out refused to do it, but Clare and Matt had warned me right from the start that that would probably be the case. You have to remember that being filmed can seem quite daunting for some people, much more so than being interviewed for a book or even the radio. I had to appreciate this would be the case for some people and just leave it. I think this was why I never managed to get a Sea Urchin in front of the camera either.

Who was your favourite Sarah band? And what was your favourite Sarah release?

Probably The Field Mice. Favourite release would probably be Shadow Factory, as I mentioned before – it totally encapsulates that time for me. I was in my early teens and that record takes me right back to then. I rarely listen to Sarah releases now, although I still go to gigs to see new bands and listen mainly to new music. I'm not a nostalgic person that believes that music was better back then, I live in the now!

Why do you think that Sarah Records never got the acclaim or praise it deserved? Do you think it was down to the fact it got such a rough ride in certain quarters of the music press?

Well, being “uncool” is cool now, but it wasn't cool then, and Sarah were deliberately uncool. They were also deliberately antagonistic and refused to suck up to the press and play the industry game – all reasons to admire them. Their attitude did mean they got singled out, and for being original, progressive and peculiar, they got a kicking. Clare and Matt also went out of their way to attack and ridicule the music press, through the literature that accompanied their records and in press releases they sent directly to them. I think what the press didn't get was Clare and Matt's sense of humour; I think Sarah was too sophisticated and forward thinking for the majority of journalists at the time – they wanted entertaining copy and bands like The Butthole Surfers taking acid, Happy Mondays necking E's and 'lads' rolling around drunk in Camden gave them more to write about. It sold them papers.

Matt are Clare have both been pretty clear that they "don't do encores", but as a fan, would you like to see Sarah brought back to life in some way, or do something else? Do you think it could survive in the modern world, now that the music business has changed so much with technology etc?

The end of the label was as important as the beginning; they released 100 singles, had a party, and published the Day for Destroying Things advert in the press. An absolutely perfect ending, and I would not want Sarah to reform in any way. Clare and Matt had a political and social conscience and it would be great if current labels learnt something from the way Sarah operated, but it would need to be relevant to what is happening now in 2015. I'm not a fan of nostalgia or rehashing the past. I liked Jesus and the Mary Chain in 1985, and Babes in Toyland in 1990, but I have absolutely no urge to go and watch them live now, I'd rather go and discover something new.

Clare Wadd & Matt Haynes

DiS: How did the idea of the documentary come about, and who was the driving force behind it?

Clare Wadd: The documentary was entirely Lucy Dawkins' idea – she approached us about five years ago, at which point we didn't know her at all – and we were initially quite sceptical about the idea, because we both hate being photographed, let alone filmed. But once we met her we both felt really comfortable with her – she was from Bristol, understood the label, cared about and understood the feminism and the politics and liked the music – but she didn't have any of the bands on any sort of pedestal, which felt really important too.

It's been a real labour of love and made on a shoestring, so has a lot in common with the way we ran the label. It's pretty amazing for a first film that it's been so well-received, being included in film festivals in Spain and across Latin America and winning a Royal Television Society Award. We're really pleased with it too – from our initial thought that she was going to do it anyway so we may as well engage to where we are now – it's a good film whether you know the label or not, and feels like a proper telling of our story.

Matt Haynes: I think Lucy had written us a few letters back at the time – she was "Lucy from Clevedon", because that's how we knew everyone in those pre-internet days. It certainly wouldn't have crossed our minds that, more than twenty years later, she'd be making a film about us!

Anniversaries for classic albums and the like are now a pretty big thing. Did you have any notions or ideas working away at the back of your minds to do something for the 20-year anniversary of the end of Sarah Records? Was it something you’d been thinking of?

CW: No, we'll probably send a tweet or two, but because the basic premise of stopping the label when we did was "we don't do encores", there won't be any compilations or boxes of the first ten singles on limited edition red vinyl or anything like that; not our style. We're enjoying supporting the film, but we aren't really great fans of either nostalgia or of repackaging "product".

MH: And obviously when we stopped back in '95 we just assumed the label would gradually fade from memory as records became scratched, CDs started skipping and tapes wore out. The idea that 10 years on, let alone 20 or 25, enough people would remember us to warrant any sort of celebration would have seemed ridiculous. We just assumed it was over. The internet, of course, changed all that, and many of those "celebrating" our anniversaries only know the songs via You Tube and MP3s. But we are hopeless at nostalgia – it's usually other people who point out that it's 25 years since our first release or whatever.

Did ether of you have any doubts about revisiting it, and that era? Sometimes, those who work in the arts are loathe to look back.

CW: We've had five years to get used to it now, and there's quite a trend for slightly obscure music documentaries at the moment – but back when it was first proposed, we were fairly baffled. We never, ever expected anyone to make a film about us – but you don't always get to control this stuff, and this one we decided to go with because we found early on we both liked and trusted Lucy. It was quite strange looking back and getting asked about some of the stuff because it's so long ago now – I'm sure we've misremembered some things too.

MH: As Clare says, our final statement, the half-page ads, said "we don't do encores", and we don't want to compromise that. We've always let other labels reissue items by individual bands, because it wouldn't be fair on the bands to say no, but we won't be letting anyone do any celebratory label re-issues!

People are often loath to look back because they find their early stuff embarrassing, and I'm sure both us and the bands would do certain things differently with the benefit of hindsight or knowledge/skills/technology acquired later on. But growing up in public is all part of it – everything was as good as it could be at the time we made it, and that's all you can ever aspire to: saying "I could do that better now" is pointless.

Was it easy to look back and go through all the music and all the memories? Or were parts of that bittersweet?

CW: We spent a lot of time last spring going through the records, photos, posters and other memorabilia for the exhibition we had at the Arnolfini gallery in Bristol when the film previewed, and that was quite strange. We're quite familiar with what there is now, but when we first started looking in old boxes, there were things we'd completely forgotten about, and other things we just hadn't looked at for 25 years. It was probably bad timing because some of it might have been useful for the book or the film – but as it turned out I think we put together a good exhibition, and it was certainly fun (if slightly stressful) to do. Parts of it were bittersweet – we were pretty much all very young in Sarah days, the bands and us (I was 19 when we started the label), so we all did a lot of growing up and sometimes it could be quite emotionally charged. There are people we haven't seen for years, old friends we lost touch with - and people who have since died; Mathew from Heavenly, Keith from Blueboy and, at the start of this year, Simon from Gentle Despite.

MH: I don't know if it says something about the sort of bands/fans that Sarah attracted, or whether we were just very lucky, but the one thing that keeps striking me is how nice everyone is! We've been back in touch with people we've not spoken to for 20, 25 years, and everybody is just really lovely, with any arguments over sleeves or track listings that we might have once had completely forgotten. We've even met some people we never met at the time – three members of the Golden Dawn came to the Q&A in Glasgow, and that's two more than we ever met when they were on the label! And FM Cornog from East River Pipe came to the New York screening – we'd not met him before either. And obviously it's fantastic that they wanted to come.

The one thing it did remind me was just how vicious some of the reviews were. I always have it in my head that some appalling things were written about us, but occasionally I worry that I might be looking back through whatever the opposite of rose-tinted spectacles are. But no, some of it was completely inexcusable, really – no wit, no insight, just bullying. And the journalists who did this had such power, because the three weekly music papers were all there was. So there's always been a slightly bitter feeling; bands like The Orchids and Blueboy should have been huge, but they were bullied into irrelevance. Thankfully, this has been redressed slightly thanks to the internet...

Why did the press have such a hard time accepting Sarah and the music for what it was, and what it stood for? It's one thing to say you don't like a certain style or sound, or to give a bad review, but some of the things that were written - such as "This isn't music, this is cancer" - are just atrocious!

CW: This got worse as the label went on and the press got simultaneously less political and more macho. The last couple years were the worst – it was the time of Oasis, Happy Mondays in a bath with Page 3 girls, IPC who owned both NME and Melody Maker launching Loaded, staffed by a lot of former music journalists. The zeitgeist was a sexist, laddish culture and sexist, laddish music, supposedly tongue-in-cheek but indistinguishable from one that wasn't tongue-in-cheek, and we were both incredibly far removed from that and actively challenged it. If you think about Oasis as the epitome of those times, they were brash and crass and obvious, and a lot of what we did was gentle and subtle and different. It was easy for them to poke fun at a label with a girl's name, at a label that was out on a limb, musically and geographically – It was bullying basically. The UK music press has always had the jokely fun element too – which is OK sometimes – but what they did with us went way beyond not taking pop too seriously.

MH: Although the press paid lip service to being right-on, the old macho rock'n'roll clichés still dominated. There’d been some respite around C86, so the backlash was in full flood when we arrived, and most of it was pretty pathetic: all the grebo nonsense, and silly little boys on Creation pulling on leather trousers and talking about "rock'n'roll". Presumably, they were terrified of having their masculinity called into question, and the press were no different – they had their metaphorical leather trousers. Music was for boys, and the only women who were allowed to play were those who were lauded for rocking just as hard as the men, or who fitted some singer-songwritery notion of femininity. Loaded and Oasis were still a few years away, but it was basically a proto-lad culture.

And there we were, calling ourselves Sarah, sticking flowers on our 7” labels, refusing to be "rock'n'roll”, saying there is another way of doing things which can even include the way you market and present records… maybe people were uncomfortable with us pointing that out? And maybe they thought that, if they kept hitting us, we’d eventually go away?

The problem is, because some journalists were so brutal and aggressive, their more open-minded colleagues wouldn’t stick up for us because they were terrified of being tarred with the same brush – they’d tell us they couldn't review something because they'd reviewed "a Sarah record" a couple of weeks earlier. Many of our good reviews start with the disclaimer "unlike other Sarah releases…", which basically means: "don't worry, guys, this is just a one-off – I'm still one of the lads". The class bully picks on someone because he's shy or wears glasses or “isn’t a real man”, and the rest of the class joins in, because they're worried he'll turn on them and accuse them of not being real men too.

And if only the loud, abusive voices are being heard, then only that side of the argument enters the public consciousness; a lot of our detractors never heard/saw anything we'd released, but still thought they knew exactly what our records sounded like and what we represented. So it all became self-reinforcing. The NME review of our final release said we never put barcodes on records (yes, we did) and gave out sweets at gigs (no, we didn't); he was reviewing the myth, not the object in his hands.

One of the things that Lucy mentioned was how forward thinking she found Sarah in terms of its politics, but the sort of things you were championing back then would still make you forward thinking in 2015! Does it make you sad or frustrated that no other label really picked up your baton and ran with it, or the same issues still exist within the music industry (and society)?

MH: Even at the time, we were always frustrated that it never really got picked up on, whether by journalists who couldn’t see beyond the supposed “tweeness” of the music – it hadn’t occurred to them that a political label didn’t have to be shouty and dour or sound like Crass – or by bands and other labels who were supposedly influenced by us and yet didn't seem to have registered precisely what we stood for, so happily released limited editions and used random female images in their marketing. Obviously a lot of what we did was quite subtle, or wrapped up in jokes and daft metaphors; maybe we should have made it more obvious!

In terms of gender politics, I think things have improved in some areas – e.g. there are a lot more mixed-gender bands around, almost as if women are being treated as musicians, rather than just decoration – but I'm not sure the power structures have altered that much, and marketing imagery is still often vile. There was a piece in the Guardian last week by John Harris, bemoaning the lack of female involvement in music; all valid points well made, but I did want to say: John, we were saying all this 20-25 years ago when you were writing for MM/NME, and all we got was abuse! (not from him personally, I hasten to add)

CW: I think to some degree it was forward thinking for a label to be doing what we were doing, and in other ways it followed from what went before, things that labels like Crass did, or to some degree bands like Chumbawamba, or things like The Women's Press or Virago Publishing. Feminism had been around a long time, and we came of age in the 80s when it was impossible not to care about politics (as it should be impossible now), and it seemed obvious that how you ran your business was political – in the same way as perhaps John Lewis would say it is now. So Riot Grrrl overlapped with us, time-wise and issue-wise, and things have changed to a degree – there are more women in bands now, and they certainly feel less restricted to doing the singing. That said, issues do still exist – we don't have equal pay, we still have men's jobs and women's jobs (I had to replace my car this morning, guess how many female salespeople I saw?), but saying you're a feminist and shouting about the issues seems to be much more acceptable (except to the social media bullies). But then, the whole record collecting elitism thing, limited editions, blue vinyl seems to have got worse.

A couple of years ago, there was a mini revival of bands who seemed to take inspiration from a lot of Sarah bands and people like the Pastels and the Shop Assistants. But even then it was dismissed as gimmicky, or lacking in substance, or in some way not to be taken seriously - all the things that were thrown at so-called twee pop. What is it about this type/style of music that causes people to have such strong reactions?

CW: That's interesting, because assuming you're thinking of bands like Pains of Being Pure At Heart or The Drums, I would say they were taken much more seriously - and certainly seem to have achieved success on a bigger scale. Perhaps I'm not plugged in enough now. I suppose men largely still control the media and some men do seem to feel like an admission that they like anything gentle-sounding, or even an ability to see any merit in it, will call into question their masculinity or sexuality or both.

MH: There seem to be certain boxes to tick if you want to be taken seriously as "an artist", most of them defining a very clichéd “tortured” (male) individual who can be excused all sorts of nonsense just because “he’s not like us, he’s a visionary, a poet…”. Which is why Mark Kozelek still has a record deal (and numerous apologists) despite verbally abusing female journalists while onstage. Being "serious" often seems to come down to not being particularly nice and not having a sense of humour and arrogantly thinking you’re from another, vastly superior planet – qualities not generally associated with twee pop. Talulah Gosh's biggest offence (as well as being two-fifths female) seemed to be that they were personable and always looked like they were having fun onstage. Ditto the Shop Assistants, and ditto Heavenly. It doesn't matter how angry or bleak your songs are, if you’re not refusing to communicate and aren’t throwing tantrums and aren’t behaving like a spoilt, stroppy, petulant little boy, you can’t be a serious artist.

I know you've both said "we don't do encores" but have you never been tempted to do something around Sarah again? Not even a concert, or some new releases? The world could use a label like Sarah existing again.....

MH: Nope! Some people have even accused us of compromise by agreeing to do Q&As for the film (or interviews like this!) – I don't agree with them, as we're clearly not resurrecting the label in any way, but it's good that, even after all these years, people are still ready to shout "sell out!" if they think we've gone back on our word. It's when people stop complaining that we need to worry.

CW: Yeah, it was hard work (though fun too, mostly!) and it was a long time ago; it was nice to run a label where the bands were similar ages to us, not us in middle age putting out records by kids. That would be kind of a weird dynamic. Some of the bands are still going, and some have reformed or have new bands, so there are concerts and club-nights and things that we don't have control over. But we very much wanted to have a definite end to the label and to stick to that – Sarah stopped 20 years ago at number 100, and that's never going to change.

http://storyofsarahrecords.com/