On paper, Mission of Burma are only a minor part of Roger Miller’s life. Prior to the band’s reunion, they had only made one studio album – the highly prescient, artsy hardcore bulge of post-punk noise that still stands up as their masterpiece, Vs.. Even adding in the four albums albums Burma have made since reforming in 2002, their discography is slim compared to Miller’s experimental solo work or the silent film scores he’s made as part of scrap metal reclaimers Alloy Orchestra. Getting him on the phone a few days after a short run of Mission of Burma shows in the States means catching Miller in between fixing up the Alloy Orchestra van and recording with percussionist Larry Dersch for their instrumental outfit Binary System.

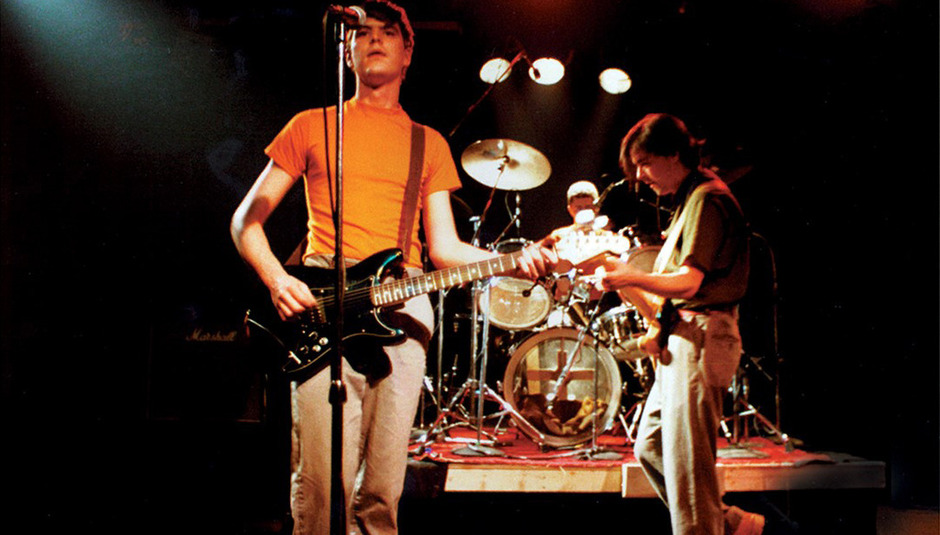

Still, it all comes back to Burma. “Mission Of Burma is the pivot of my life,” says the band’s guitarist, reflecting on their formation in Boston in early 1979. “This was what I’d been building for all my life since sixth grade when I saw The Beatles on TV. Even now, I’ve got pieces performed at the New England Conservatory of Music and even the guy there who was the head of music, he’s a piano player who plays Brahms piano symphonies, stuff like that – he had an ‘Academy Fight Song’ single that he wanted me to sign.”

That track – Burma’s first single – opens the latest reissue of their landmark 1981 EP, Signals, Calls and Marches. Beefed up over years of repressings with the addition of ‘Academy Fight Song’, it’s B-side ‘Max Ernst’, and two previously unreleased tracks from the same session, the record is the definition of a flawed classic. Bassist Clint Conley’s pounding ‘That’s When I Reach For My Revolver’ is as brilliant an anthem as Burma would ever write, the distinctively choppy post-punk that would become their calling card is foretold in ‘This Is Not A Photograph’ and the woozy ‘All World Cowboy Romance’ is heresy against the punk orthodoxy that dominated the underground of the day. But even the band weren’t happy with the EP at the time, it’s gentle (you might say radio-friendly) production failing to capture the deafening fury of Burma live.

“I’ve come to accept Signals, Calls and Marches a lot more,” says Miller. “Although, the problem with Signals, Calls and Marches is we hadn’t really found our voice yet. The songs are strong: we do ‘Red’, ‘...Photograph’, ‘...Revolver’ on a regular basis and knock people out, but we hadn’t quite found our voice. The sound of the guitar isn’t quite right, the bass, the way we go about recording, we hadn’t quite figured it out yet, whereas we got it on Vs.. That’s why Vs., to me, is a vastly superior record.”

From the get-go, it’s hard to disagree. Conley’s bass throbs through Vs. opener ‘Secrets’ like a Joy Division track played double-time, getting lost within a minute beneath drummer Peter Prescott’s myriad fills, the palpitating flutter of sound engineer Martin Swope’s tape loops, and the distant screams of bandmates. Burma take the energy of hardcore and make it ten times more interesting with their outlandish nods to free jazz and psychedelia. After that, you can almost play indie rock bingo as you tick off the bands prophesied in the Gospel According to Burma: the gang punk-funk of early Fugazi in ‘Weatherbox’ and their later feedback-based experiments in ‘Fun World’; The Nation of Ulysses’ jittery politicising in ‘New Nails’; shades of Interpol in ‘Trem Two’s instrumental passages; even The Futureheads’ in the play-it-as-fast-as-we-can-then-do-it-faster knees-up artrock of ‘That’s How I Escaped My Certain Fate’. As Michael Azerrad writes at the beginning of his chapter on the band in the essential Our Band Could Be Your Life, “Mission of Burma’s only sin was bad timing”.

Well, that and being a bit too loud. Before joining Mission of Burma, Miller suffered from tinnitus, a condition inevitably made worse by him joining a noisy punk band. He persevered, but by the end was having to wear earplugs and ear defenders at gigs. Mission of Burma split in 1983 to preserve Miller’s hearing, and for years a sense of unfulfilled potential surrounded them. In talking about “bad timing”, Azerrad’s making the point that if they’d only clung on a little longer, the national alt-rock infrastructure that was only just taking shape when they split might have dealt them a different hand – as it would for major label stars Hüsker Dü, Dinosaur Jr, Sonic Youth and, of course, Nirvana.

“We started before all those bands and it was conceivable that if we’d kept going we could have done something like Sonic Youth did,” says Miller. “Which is all fantasy because it didn’t happen but it would have been something like Sonic Youth. We wouldn’t have had massive hits – I mean, Sonic Youth never had massive hits, but they got this very big underground status. It is conceivable we could have done that. But we didn’t, so who knows.”

Not at the time, at least. But like Slint, American Football, Refused and plenty of other young musicians who wrote some great songs for fun and disappeared with a shrug, an audience for Mission Of Burma formed in their absence. In particular, new fans were switched on when Our Band Could Be Your Life came out in 2001 and Mission Of Burma were spoken of in the same breath as Black Flag and Fugazi. “We sold so many less records than those bands, we got so much less press, were so much less famous than all those bands,” says Miller. “We had always considered them to be our peers but that they were so much more massively bigger than us. When he [Azerrad] presented us in that context we were just stunned.”

Spurred on by the fresh attention, a year later Mission of Burma played two sold-out reunion shows at Boston’s Irving Plaza. Martin Swope politely declined to take part: his role in the band, which placed him at the sound desk rather than onstage, always suited his retiring nature and, according to Miller, Swope eventually “dropped off the map” altogether after moving to Hawaii. Though all was amicable (the pair actually continued to collaborate as Birdsongs of the Mesozoic after Burma’s initial split) Miller hasn’t heard from Swope in a decade.

Shellac bassist Bob Weston was therefore drafted in to fill the weirdest shoes in rock. At shows and in the studio, as Swope did, Weston records fragments of the band’s music to tape as they perform it, manipulates the audio and bounces it back as part of the song. As a renowned audio engineer, he was an obvious choice. “Bob Weston had played in Peter Prescott’s band Volcano Suns, he’d played in my avant garde chamber orchestra XYLYL and he had produced Clint’s band Consonant a few years before Burma, so it was a very natural fit,” says Miller.

“He tours with Shellac, he’s one of the major mastering engineers in the United States in Chicago and yet he still makes time to tour with Burma because he’s obviously completely insane,” he adds, laughing. “I mean, what the fuck?”

“We’re kind of amused by him because he’s a little more upfront than Martin. Martin was always very, very subtle and sometimes Bob will do some crazy shit with loops that’s more over the top, and we find that very amusing.”

This kind of progression, amusing or otherwise, is key: since reuniting, Mission Of Burma have never looked back. Although their audience numbers dipped once the punk generation was done making up for missing them the first time round, younger listeners have taken their place, following glowing reviews for Burma’s post-reunion material from the likes of Pitchfork. Miller takes particular pride in 2006’s The Obliterati and 2012’s Unsound.

Recent gigs have featured a couple of newer songs that were written in the wake of Unsound, but there aren’t currently plans for a follow-up. Miller admits that his tinnitus worsened noticeably after Burma's last European tour, which may help explain why activity since has been more sporadic. Already, he performs without monitors, with his amp turned away to the side and with Prescott's drum kit shielded behind screens to prevent further damage; at practice, he stands in a separate room to the rest of the band. "I was talking to Clint about it recently and he also has tinnitus, he just doesn’t talk about it," says Miller. "He says his ears are ringing more too!"

The only date in the diary is a support slot opening for the Foo Fighters at the 30,000-seater Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox. It’s an improbable proposition for an experimental band still committed to the club circuit, though Miller offers a typically artistic take on it.

“As far as I’m concerned, it’s greatest value is that it’s going to be weird as fuck,” Miller laughs. “If you look at it like that, well okay, that's an interesting experience, you know? As far as the actual rock experience, I would rather play the Sinclair in Boston.”

Still, for all that’s said about Mission of Burma being ahead of their time, would it not have been better if they’d arrived at exactly the right time? Wouldn’t it have been fun to see what the mainstream might have made of them, in an age when Sonic Youth could become major label stars? Really, shouldn’t it be Mission Of Burma headlining that baseball stadium in a few days?

“I don’t really have any regrets about it because we folded for such a weird reason,” says Miller. “It was the perfect setup for the reformation of later. We were a weird band. We didn’t care about being famous. We cared about being famous and looking good on stage much less than a lot of other bands who were of our ilk. It’s almost like we’ve accidentally constructed this perfectly weird thing. We were cut off before our time, we came back, people were freaked out and then we just picked up where we left off because we never fucked up.

“We didn’t get sick of each other, we didn’t get sick of touring. We just folded for a weird reason and that was it, and we never ran out of creative ideas. In fact, Vs. was kind of the blueprint for lots of material into the future, so when we reformed in 2002, that material appeared. It was as if it was 1984. It’s as if we plugged right in, as if nothing had happened. It makes for a real interesting story, I’ll say that much.”

The remastered Vs. and Signals, Calls and Marches are out on Fire Records as part of the Fire Archive on Friday 10th July.