The two famous French festivals of the arts I went to in 2015, Le Festival d’Avignon and Rencontres Trans Musicales, represent different ends of the same rather enviable spectrum. The tonal differences are significant but both ultimately exhibit dimensions, qualities and component parts that, if not unique to France, certainly feel pretty French: an unashamedly highbrow investment in the new and the experimental; a central programme buttressed by a chaotically creative fringe – suggestive of a wider culture of artistic elites emerging from established grassroots structures; daily evidence of vibrant scenes flourishing in fifth, sixth, seventh cities, thanks to a far healthier regionalism than exists anywhere in the UK – and of the unrepressed technicolour of non-Anglophone art; a willingness to programme late into the night; and whacking great local, national and let’s face it probably even continental public subsidies.

But if Avignon, contained within honey-coloured papal cloisters in Provence, represents – I don’t know – the Cezanne of the French festival calendar, then Les Trans is probably its Le Corbusier: a machine for partying in. Housed in a massive, dystopian Tetris game of out-of-town aircraft hangars, it showcases music from around the world that is really, genuinely new, unlike the new work by established theatre-makers that Avignon peddles. Shows take place in venues designed to give first album artists the rig of their lives, an unprecedented opportunity to be the best version of themselves they can be, while at the same time exposing them utterly. Because in these 10,000-capacity cowsheds, there are no distractions. The premise might be similar to the Great Escape, but Les Trans doesn’t have Brighton going on in the background.

The overall impression is of a massive, egalitarian, accessible experiment, based on the thrillingly optimistic premise that – in France, anyway – there is a large enough music audience with a lively enough cultural curiosity that it will schlep all the way to Brittany for a midwinter festival lacking in a single recognisable headliner. A long-running experiment, that is, with predictable outcomes: this year’s Rencontres Trans Musicales was the 37th edition, attended by the usual 60,000 ticketholders from all over France and a sizeable contingent of journalists, promoters and A&R folks from across Europe. All were reasonably confident that this year’s line-up would maintain the festival’s remarkable reputation for picking winners at the outset of their careers, from the Sugarcubes in 1988 to Janelle Monáe 22 years later.

Les Trans’ qualitative consistency is mostly down to the curatorial vision of founders and co-directors Béatrice Macé and Jean-Louis Brossard, students at the University of Rennes who started organising zeitgeisty shows and festivals in the city’s underused venues in the late 1970s and have basically carried on doing that ever since. Brossard, now a silver-haired, Ralph Lauren-ish figure, spends the year attending festivals around the world and listening to thousands of demos and promos, picking wheat from chaff – and plays hype man to personal favourites at the festival itself. His line-ups once introduced the key emphases of the coming mini-era to European audiences: grunge (Nirvana) in 1991, Bristol trip-hop (Portishead, Massive Attack) in 1994 and new rave (Klaxons) in 2006. If recent editions appear more scattergun – 2015’s festival was very evidently the work of curators who like pretty much all the genres – that probably reflects the eclecticism Brossard has picked up along the way, as well as the globalised, post-genre tendencies of contemporary music.

Rennes is an appropriate home for this music laboratory. A young, open and egalitarian university town accommodating over 65,000 students and a Socialist mayoress, it feels like a 20th-century cousin to Bologna, Italy’s city of scholarship, man buns and anarchist graffiti. Georges Maillols’ pioneering honeycombed high-rises loom over its few old buildings, sleek and dazzling in a way UK towerblocks are never allowed to be. Opposite Le Liberté, the venue where Brossard puts on shows throughout the year, is Rennes’ new ‘Champs Libres’, a remarkable slab of pink granite designed by Christian de Portzamparc that I wandered into one afternoon, before settling on a sofa on the fifth floor of the library, to read the new Asterix album as the pale winter sun dipped behind the city. At no point was my bag searched; at no point was I asked for a membership card.

Unfortunately, the festival itself wasn’t in a position to be similarly chill. Just a few weeks before the first night of Les Trans, three gunmen wearing suicide belts walked into one of Paris’s most famous gig venues and shot 89 people dead. An ISIL statement the next day sought to define the attack in specifically anti-music (as well as anti-French) terms, referring to ‘the Bataclan where hundreds of idolaters were together in a party of perversity’. Les Trans issued a statement the next day confirming that the festival would take place with increased security. Macé talked of being ‘stunned by so much hatred. It's hard to think that we could be disqualified as human beings because we have a drink on the terrace or go to see a concert. [But] since November 13, every day, we move from despair to fierce determination … to resist.’ To their credit, not one artist cancelled.

The main festival was able to brush off the impact of the enhanced security measures, which were felt before one got onto the shuttlebus to the ‘Park Expo’, after one got off the shuttlebus, and twice on the way into the hangers – I’ve been searched less in airports. However, once you were in you were in, and heavy-handed security was sufficiently absent that, for example, I shared a joint with a radio DJ on the shuttlebus back to Rennes on the first night. It was felt in the Bar en Trans, however. The unaffiliated little brother of the main festival takes place in the venues around Rennes that Les Trans used to fill, offering a lottery of mostly French artists to hipsters for whom the just-breaking bands at the Parc Expo are already too big to be interesting. This vibey, makeshift fringe which usually encourages audiences to ebb and flow in and out of venues continuously was totally spoiled by tightened entrance checks, explained a woman working with a moody French electropop band called Camp Claude (good vocals, bad lyrics). Still, it’s nice to have a steady supply of moody electropop when you’re pre-drinking, and my god, it remains something French audiences have a limitless appetite for.

Much less conspicuous than the security arrangements was the atmosphere of mourning or special solidarity I expected to find. The clattering, Grime-inflected London songwriter Georgia interspersed tracks that were both synthetic and raw with platitudes about music bringing people together in dark times etc., and everyone just got a bit embarrassed. The emotional narrative that got people fired up on the first night of Les Trans was, rather, a classic underdog story: Her, a local band who at their best sound like a sparser, more Simon Le Bon-ish Jungle, packed out a whole cowshed, having worked as roadies at Les Trans just a few years before. Every mistimed fist-punch told an emotional story of triumph over adversity etc., which was a little at odds with the glassy sheen their music promises, but charming nonetheless.

The contrast between an artist like Georgia and a band like Her is illustrative of a phenomenon that became more apparent the more sets I watched at Les Trans: music from the UK is in a far messier, nervier, more postmodern and post-genre place than the sounds coming out of pretty much anywhere else. Particularly France. On Friday night, Georgia was sandwiched between sets by two other London artists, Clarence Clarity and The Comet is Coming. On record, the former sounds like a big beat Ariel Pink with an anti-design fetish rooted in the mid-noughties (I suspect he’s older than people think) and the latter like if Acoustic Ladyland were into retro computer games about space. On these massive stages, though, the layers of digital noise dissipated and London started to sound confused and insipid. Clarence Clarity looked particularly exposed up there, the optimistic nods towards Prince falling away leaving just another Goldsmiths wanker. To be fair to The Comet is Coming, when they don’t sound like electro-swing for electro-crusties they’re actually kind of great.

Compare these jangling bags of urban and digital anxieties with the better French artists playing at Les Trans, who were relentlessly self-assured in their limitations, and invariably killed it in the cowsheds. Actually, it’s not really fair to describe 3SomeSISTERS as limited, although the specificity of their concept is a brilliant defence mechanism for festivals: two men and one woman all dressed to varying degrees like Elizabeth Taylor As Cleopatra doing a cappella takes on Grace Jones funk, albeit with numerous am-dram and ambiguously Arabian flourishes, accompanied by a kind of electroclash gimp bashing a drum machine etc. Fortunately everybody involved was a very good singer and, to quote the festival programme, ‘in addition to their sexy music, the quartet wears wigs on stage and gives a momentous performance’. Similarly enjoyable at the time, but in a manner that makes me suspect I won’t return to them on Spotify, were Totorro, another Rennes band which plays an endearingly guileless double-drummer version of post-rock pitched halfway between 65days and Nordic euphoria.

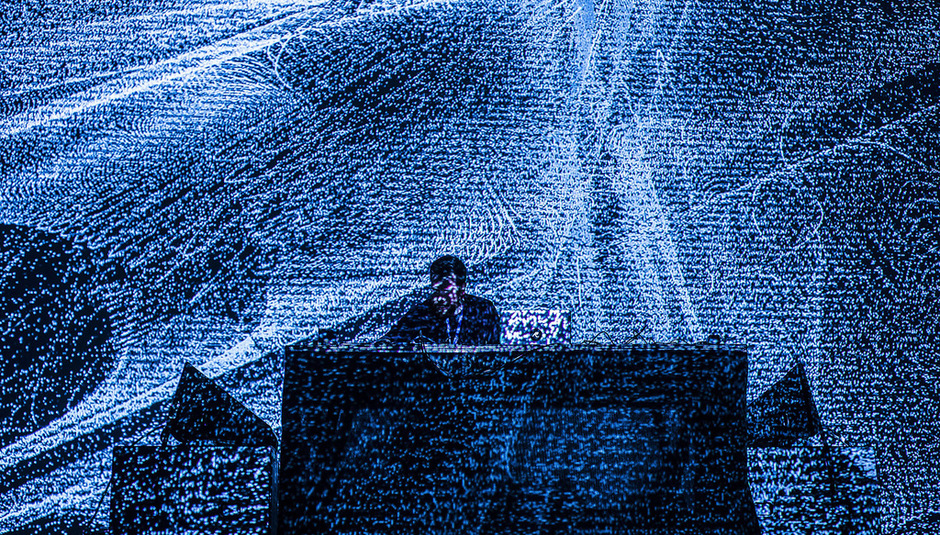

The distance between London and Paris was less apparent in the hangar dedicated to electronic music. Jacques, a tonsured weirdo from Alsace, constructs intricately ominous tracks from found beats and gongs and birdsong, but he played them really, brilliantly loud. Leicester-born labelmate of Nils Frahm, Ólafur Arnalds et al Rival Consoles (pictured above) is similarly delicate in his compositional technique, creating pointillist suites of finely calibrated yet also deeply transcendent melancholy. His set, which filled the festival’s largest venue with crystalline labyrinths of melody and shockingly beautiful projections, was the best thing I saw and heard in Rennes. Jacques was up there too.

Elsewhere, the pleasures to be had were both local and far-flung. In Rennes I got over my hangovers with stacks of wonderful 30 cent oysters from the Marché des Lices, then sank back into them thanks to gallettes stuffed with andouille de Guémené, a smoked sausage created from 25 layers of pig intestine, which tasted like hickory and iron and, if I’m honest, pigshit. Then I went to see bands from the USA and Canada, Mali and Thailand. In order, then: I enjoyed Queen Kwong’s internal tensions – between Carré Callaway’s mercurial prowl and her band’s roidy stadium tightness; Dralms combines an elegantly low-key, slightly jazz vocal with moments of enjoyable, Bond-themey melodrama; Imarhan create layers of superfast fretwork that start to function almost like drones, then work them into songs that sound like a funkier, more anthemic Tinariwen; and Khun Narin’s Electric Phin Band, aged between like 28 and 80 and wearing matching red tabards, basically played one single never-ending psychy wig-out jam that forced traditional Thai instruments through distortion pedals in a manner that regularly resembled hair metal, and I loved it.

And yet despite these Breton and world-spanning distractions, I continued to think about the Entente Cordiale. Throughout Les Trans I couldn’t shake the feeling that something essential about the relationships between culture and place, France and Britain, music, audiences and funding, was being illustrated by this peculiar festival.

40% of Les Trans is paid for by public bodies including the Métropolis of Rennes and the General Council of Ille-et-Vilaine in order to ensure that the caner kids of Brittany – because that, rather than ATP demographics, say, is the festival’s primary audience – get their rocks off to the sound of Khan Narin’s Electric Phin Band, rather than EDM. Does this represent value for money? I think the whole point might be that this is the wrong question. The unique joy of l’exception culturelle seems to be that the French throw a shedload of money at a weird idea to make sure it really works, without focussing too much on efficiency. Framed in these terms, the erection of Reading Festival rigs for Algerian funk bands in aircraft hangars on the outskirts of Rennes suddenly starts to make the same kind of sense as, for example, converting a 14-century papal palace into a vast outdoor theatre stadium in order to stage an iconoclastically naked version of King Lear on motorbikes. Avignon’s public subsidy pays for 55% of the festival. The set-up could obviously be made loads cheaper, but efficiency savings would undermine the epic indulgences that make these festivals world-famous; without them they’d quickly crumble like le Pont d’Avignon. Plus, any assault on French funding of the arts would quickly be countered by the kind of strikes that resulted in the cancellation of various festivals in 2003.

A festival like Les Trans also reveals that l’exception culturelle is a double-edged sword for something as temperamental as music, however. Because it’s difficult not to see a band like Her – hearty and competent, fun but irrelevant – as the inevitable product of a music industry that mollycoddles French artists in terms of everything from recording and touring costs, through to download revenues and radioplay. I’m not, by any means, suggesting that a brutal, post-subsidy free market would automatically catalyse better music – there is lots of evidence to suggest that the exact opposite is true, actually, that art without state support is invariably risk-averse. But it’s important to recognise the risks of supporting mediocrity as a point of principle. And the thrill of raw, scrappy music with its roots in DIY scenes, cut from the edge of the present – even though it’s unlikely to look very impressive in the context of Le Trans’ LEDs and lasers.