Music don't sound like it used to.

Quite literally in fact. The way we hear the music of the 1970s, 1930s, or even the 1780s is not the same as those at the time heard it. We might think of music as if it is mere vibrations in the air which travel straight to the ear where they become sound. This is because the process of interpretation when we listen to music is unconscious and invisible to us. Music that we enjoy seems to be transparently great, as if anyone, anywhere, could enjoy it. But without that influence of culture, that vibrating air is just sound; society turns it into music.

For example, the guitar solo in "Sweet Child O' Mine" is thrilling because of the place of rock music in Western culture, the place of the electric guitar in that genre, and the way Slash embodies an idea of rock & roll cool (amongst other things). The very same guitar solo is not thrilling if: a) you think Guns 'n' Roses represent bloated '80s decadence and resent my trendy, modern reclaiming of their work; b) you've never heard an electric guitar before. We had to learn to associate guitar solos with transcendence or rebellion, the meaning is not inbuilt in them. Welearn to associate sounds and images with feelings; if you played OK Computer to aliens, they're not going to get why you think it's great (not even 'Subterranean Homesick Alien').

The sociologist Howard Becker describes a process of acculturation in his study Becoming A Marihuana User. In this study, Becker argues: "An individual will be able to use marihuana for pleasure only when he ... learns to recognize the effects and connect them with drug use; and ... learns to enjoy the sensations he perceives." As Becker writes, "Marihuana-produced sensations are not automatically or necessarily pleasurable. The taste for such experience is a socially acquired one, not different in kind from acquired tastes for oysters or dry martinis." In this same way, we have learnt to enjoy certain types of music, even if that learning process was invisible to us. When we learnt the history of Guns 'n' Roses, watched their videos or saw Terminator 2, certain meanings became attached to their songs. We began to enjoy those songs when our worldview saw us associate with those meanings; when we sought to rebel from our parents, these symbols were the language of our rebellion.

When music of the past sounds better to us then, we can't take this feeling as objective proof that music was better in the past. The idea that music was somehow better in the past has literally existed for at least hundreds of years - certainly back to the birth of romanticism. In 1899, for example, music historian Hubert Parry said: "The old folk-music is among the purest products of the human mind. It grew in the heart of the people before they devoted themselves so assiduously to the making of quick returns". Update the language and this is a fairly typical statement of any jaded music snob telling you why their preferred music is the best.

This is really romanticism as applied to history. We imagine that somewhere in the past, music was purer, life was better, and musicians weren't looking to make money. When doing this, we're looking through history and imagining that we're looking through it objectively. This is impossible; as the historian E.H. Carr wrote in What Is History?: "We can view the past, and achieve our understanding of the past, only through the eyes of the present". This means that whether your 'golden era' is the psychedelic '60s or '90s house, your understanding of it is based in the past and the present. When you hear The Doors or ‘Music Sounds Better With You’, your perception of the song is affected by your understanding of its history or, if you were alive, your memories (which are inevitably rose-tinted). The "authenticity" that you might hear in genres of the past says more about you and the current day than it does about the reality of the music in question. The music fan who is dissatisfied with the time they live in searches for an imagined authenticity in the past and interprets it to their own needs.

The thing about authenticity, then, is that it's vague and subjective and can be read by different people into different things at different times: what was 'inauthentic' pop to our parents might seem like the realest thing to us. What was 'commercial music' in the past, no longer sounds like commercial music to us today. The meanings of music, then, are not fixed. We don't associate the pop of the past with crass mass-produced capitalism like we do the music of today (this is not to say this reading is correct). People of the past might have learned to associate this pop with 'inauthenticity', we might not have. Trendy modern vaporwave artists or musicians like Ariel Pink are even able to make hipster-approved modern music out of what was considered the height of 'bad taste' in its own time.

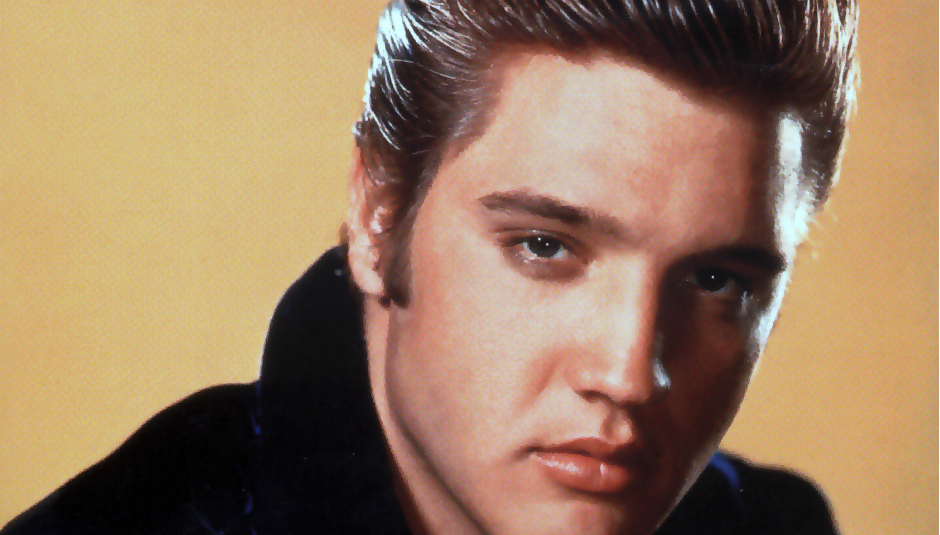

Part of this is that we hear music in terms of what came before it, while people in the future can also hear it in terms of what came after it. Hearing Elvis in 1956 it might've sounded like wild, syncopated, sexual music in comparison to Sinatra, but these days, having heard everything from hip hop to drum & bass, it no longer shocks us. In the exact opposite way, some listeners today will love the analogue roughness of Elvis' production which might sound raw in comparison to the auto-tuned pop of today. To explain this, musicologist John Covach uses the important idea of "musical worlding" where "listeners organize new musical experiences in terms of previous ones: any new song is heard in terms of other songs the listener knows". We live, then, in very different musical worlds from people in the 1950s.

The sounds and meaning of entire genres can also change as cultural opinions shift around the genre themselves. Disco became a trendy, hipster music of choice when the music aged, our attitudes towards LGBTQIA people changed, and it became the historical precursor to house and techno. Hipsters of the day might have generally scorned it but we now live in different musical worlds to them. These appreciations of past musics often have very little to do with what the original makers of the music thought of it. The rural musicians who played what we now think of as 'folk' music were assumed by leftist, educated song collectors to be authentic representations of dying cultures in dire need of saving. Folk song collectors believed the music played by these rural musicians to be 'pure' music unsoiled by the failings of capitalism. However, these singers rarely thought of themselves in these terms; they might've learned songs from the radio as opposed to 'ancient lore', and many even had aspirations to be stars.

In the case of Delta blues, the people who we value today of that genre, like Robert Johnson, might've been unknowns at the time but they didn't necessarily want to stay that way. Johnson's repertoire consisted of much more than the songs we are left with today. He was an inveterate showman that would have to play Broadway songs alongside country, jazz, and "Hellhound On My Trail" to keep his audience interested. As Elijah Wald points out in his Escaping The Delta, blues was mainstream black pop music. He writes: "Robert Johnson and his peers were intelligent professionals, well versed in the trends of their day". However, the dominant image of Johnson in our collective mind is as a struggling, rural musician playing his dark, serious music in opposition to any ideas of showbiz or entertainment.

These ideas from folk music tend to affect how we hear most music of the past. As we aren't a part of the original context Robert Johnson was making music under, we hear his music through what Elijah Wald calls "the filter of rock & roll". To the people that 'discovered' Johnson's music, it seemed 'raw' and anti-commercial compared to the music they knew. According to Elijah Wald, this is totally different to how Johnson would have seen it. As Wald writes: "The Robert Johnson that most listeners have heard in the last forty years is a creation of the Rolling Stones. Indeed, for most modern listeners, the history, aesthetic, and sound of blues as a whole was formed by the Stones and a handful of their white, mostly English contemporaries." This idea,that music comes to us through the lens of other fans and critics, is crucial. The 'authenticity' of the blues was something white fans read into, as they heard it as a precursor to rock & roll.

We can see that we don't hear music in a cultural vacuum; it's not objective. By listening to a "classic album" like Daydream Nation or Revolver, you aren't hearing a fresh new work, you are hearing it through the position it holds in culture. As these albums get referenced in histories, films, conversations between cool people, and 'best album of all time' lists, they acquire an importance that gradually adds meaning to the album itself. This isn't to say that you will like the album, more to say that it fosters a certain understanding of the music. As Carys Wyn Jones writes in The Rock Canon, "The more an album is praised by a respected artist ... the more value is attributed to it. If, in turn, an album is already established as 'great', artists ... will gain respect for having recognized its importance". When hearing music, you're not just hearing the sounds and appraising them, you're enjoying a whole group of ideas about culture and identity.

People, then, who don't associate with what they believe pop music represents are going to listen to music that represents their 'outsider' status. They can imagine that they could have been happy in the 1960s when pop music was Pet Sounds - although its likely their 60s equivalent would've thought that was worthless pop and only would've listened to blues or modern jazz to get their needed outsider status.

History is never neutral. It is the human interpretation of the past. It's always warped in some way by the historians (or critics) who collect it. E.H. Carr argued that if history is a procession, we aren't given an objective bird's eye view, but the partial subjective view of a member of the procession: "The historian is part of history. The point in the procession at which he finds himself determines his angle of vision over the past." This is not to say that there is anything wrong with loving music of the past, but just to understand that your music taste is socially constructed. Your taste reflects a complex idea of how the way you relate to the world, and how you want the world to relate to you. The ideology through which you turn sounds into music might be invisible to you but that doesn't mean it's not there. You owe your entire identity and even your idea of identity to society. Try and remember this when you sneer at people who don't like The Beatles.