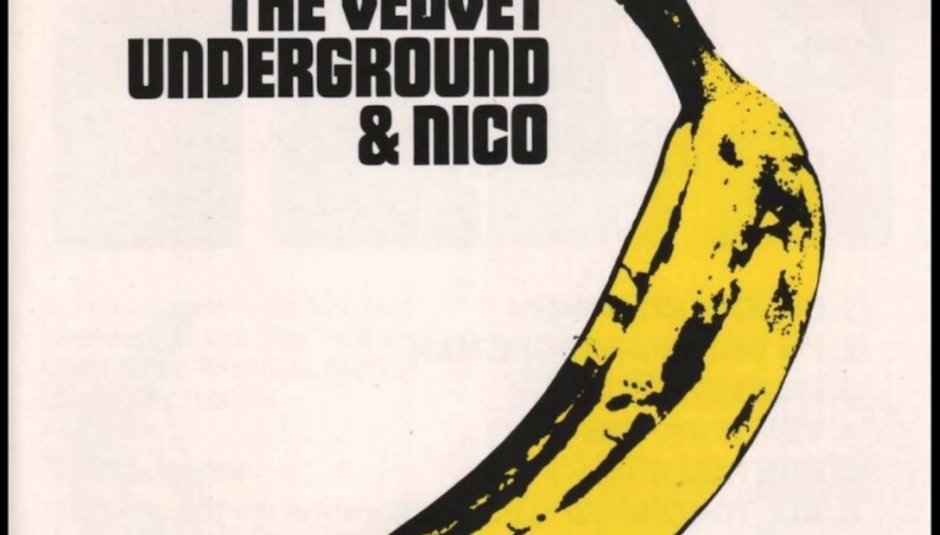

I almost feel for the guy who yelled "Judas" at Bob Dylan in 1966. That single word managed to articulate the then common view that it was impossible to say anything artistic with an electric guitar. Here we sit, comfortably on our side of history, laughing at him for his foolishness. You'd probably feel the same way if you went to see Aphex Twin play a set of David Guetta-ish house — only to be a punchline to future hipsters for whom David Guetta has inexplicably become the next Phil Spector. Little did that heckler realise that people were about to start taking “pop” music very seriously indeed. And who better to epitomise this but a band with a legitimate fine artist as their mentor?

The Velvet Underground & Nico was the point where 'rock', the art-form, was born. The Beatles and Dylan certainly got the ball rolling, but The Velvet Underground arrived fully-formed with their art-rock fusion. The band bastardised three-chord rock & roll with modernistic noise, minimalism, and a romantic link between avant-garde sounds and non-traditional lifestyles. In his lyrics, Lou Reed actively sought to express the thoughts and desires of the down-and-out; while other musicians of the day might have euphemistically mentioned "getting their kicks", Reed gave names to the demons he saw. Although the band might not have directly been shooting smack or involving themselves with sadomasochism, their interests in these topics were telling. Rather than shrinking away from rock & roll's low-down image, they actively encouraged (and romanticised) the link between rock & roll and the outsider. Reed detailed this world so well that many have likely missed the fact that he's singing in character: there's a good chance it started as many drug problems as it has bands.

The impressive thing is that the physical sound of the band seems to be as puritanically offensive as the lyrics. This is certainly one of the all-time great albums for guitar (and viola) noise. Throughout its duration, Lou Reed and Sterling Morrison's guitars shriek and squeal with expressionistic desires — the kind that blues licks just couldn't capture. That feeling that makes abstract paintings so stimulating — of rules being violated, of scribbling outside the lines of convention — can be heard in the playing on a track like 'Run, Run, Run' or 'European Son'. In the former, Reed's volatile guitar sits right on the point of feedback. Occasionally he submits and it bursts into flaming noise; at others, he manages to quell the blaze with scurries down the guitar's neck. In another breathtaking moment, during the climactic build in 'Heroin', John Cale makes his viola howl like a dive bomber. The bomb is dropped. It hits the protagonist's nervous system. The heroin is in his blood, and his blood is in his head. We're left with Cale's viola sitting on the edge of harsh feedback and angelic drone.

There's more, though, to the Velvet Underground than sleaze and noise. The Velvets were equally capable of dreamy impressionism as they were sadistic expressionism. While at first these might seem like opposing viewpoints, really these are just two sides of the same coin. Each in the hands of The Velvets seems born from a complete detachment from the world and the pleasures it normally provides. George Orwell once wrote, in an essay on Henry Miller's Tropic Of Cancer, that the romantic hedonist lives as if inside Jonah's whale: "The whale's belly is simply a womb big enough for an adult. There you are, in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens". This description is as apt for 'Heroin' as it is 'Sunday Morning'. The latter conjures up nothing less than one of Erik Satie's 'Gymnopédies' reborn as a '60s pop song.; in it you can almost hear the world trying to reach you through the blubber, yet you passively stare back, sunglasses on, faintly listening to reality's echoes.

The great thing about the first album is that it brings together each of these sides of The Velvet Underground. Their later albums generally separate them into loud, quiet, and pop (respectively). Here the band can play rock 'n' roll on 'Waiting For My Man', noise on 'European Son', and pop on 'Femme Fatale', and still seem like one cohesive group. They made it OK to simultaneously be as out-there as 'European Son' and as pretty as 'Femme Fatale'. The group's combination of their avant-garde and pop leanings can be partially explained (and vastly oversimplified) by the bringing together of Reed's background as an in-house songwriter for Pickwick records and Cale's in avant-drone music with La Monte Young. Combining the experimental and the catchy has been a significant part of the popular music landscape since the Velvets first appeared. Fittingly, one of Lou Reed's last public moves was to write a glowing review of Kanye West's Yeezus — an album very much following in this lineage.

Because of this unification of the popular and the difficult, many of the most important artists since 1967 have painted with sound. The people who fell in love with the Velvets saw in them a postmodern world where a serious artist could work on a mass scale. Here marks the point where those old values of high and low art lost any kind of easy definition. This meant that popular culture could be valued as the vibrant, intelligent, and creative field that it is, although this jettisoning of artistic talent into the popular realm sadly seems to have left the traditional fine arts largely culturally inert. The contemporary art world seems a lot like Lou Reed's solo career (according to Trainspotting's Sick Boy): "Not bad, but it's not great either. And in your heart you kind of know that ... it's actually just shite." The Velvet Underground & Nico was the point that pop and art started to speak the same language, and it was good.