Soundcheck over, Lambert is relaxing in the bowels of Oslo’s Kulturkirken Jakob sipping on sparkling water and eating Haribo. I’d been led to believe that he’d be wearing his famous mask – a somewhat unnerving creation that’s part Donnie Darko, part African warrior – but it’s sitting on the sofa next to him. Unpretentious and a little shy, he’s excited about his forthcoming European tour, of which tonight is the first date proper. It’s in support of his new album Sweet Apocalypse, a masterful collection of contemporary classical instrumentals that is by turns hypnotic, sombre, and moody. Unsurprisingly, given the title, it concerns the dystopian future we’re fast racing towards, and trying to find moments of beauty amid the carnage.

The man behind the mask “became” Lambert in 2014, but he’s been sat behind a piano for a lot longer. “I had a teacher from a very early age, maybe five,” he says of growing up in Hamburg. “It wasn’t strict, like: ‘You have to be classically trained’ but I remember I had to do it. My parents were insistent. When I was a teenager, I wanted to quit and play the drums. They said: ‘Well, you can play the drums, but you still have to play the piano.’”

Pushy parents can be the worst, but he’s at pains to point out they were simply trying to give him opportunities. “Music always played a role in our house, and they just thought it was important for their children to learn instruments. My father plays the cello, but they weren’t professionals or anything like that.”

He remembers being into the Beatles at Kindergarten – “I just liked the melodies, and would make up lyrics myself because I couldn’t speak English” – and tells how his teacher would re-write the arrangements so he could play approximations of the songs with his small hands. A change of teacher when he was 14 opened the door to improvisation, and sent him down the path he follows to this day.

“That was my first real experience on the piano” he remembers, “and how it can be a lot of fun. From that age, I developed an interest in being able to rule the instrument, to control it. I wanted to know what I was doing when I was playing, and to be able to improvise you really have to know the instrument and the keys.”

Despite studying the greats such as Chopin and Bach, the endless practice required to be technically advanced didn’t appeal. “It was never my interest,” he says, “and I couldn’t compete with that. I just wanted to write tunes. Besides, I don’t think you have to be a great pianist to make great music on it.”

He’s certainly doing fine when it comes to the latter, and is one of the most acclaimed new artists in the world of contemporary classical. From the wistful pomp of the title track to the quiet poise of ‘Parasites To Ourselves’, Lambert excels at creating and sustaining moods, adding just enough orchestration to fill out subtle layers in his songs. There are mournful strings and horns scattered throughout, gently shuffling around the piano, and a deep sense of drama runs through all twelve songs. I ask about this darkness, and how it seems to sit in opposition to someone so enthralled with the Beatles.

“But you have a lot of drama in pop music. I mean, that’s what a lot of pop is about, the drama, don’t you think? Especially lyrically.” There’s not a lot in ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand’ or ‘Please, Please Me’ I reply, but he disagrees. “Paul McCartney is definitely an influence, not directly, but the way he writes. If you listen to ‘Sweet Apocalypse’ you have the eighth notes, you have this pattern going through it. It’s not that I stole it from anybody, but if you played it on guitar and put some delay on it, it wouldn’t be so far away from a Coldplay song.”

He says he “wouldn’t mind” if he inspired the same emotional, lighters-in-the-air moments during his concerts that Chris Martin & co have become famous for, and that ultimately he’s aiming for that same connection between artist and audience. “This is why I don’t see myself as a classical composer; I’m more of a songwriter. Classical has always been an influence and can be very dramatic, but I don’t agree if you say: ‘There’s a contradiction between drama and pop’, because I think they belong together.”

Performance wise, drama is not something he lacks. A Steinway is sat on a raised platform in the middle of the church, giving the audience the chance to observe from any angle. Clusters of candles are dotted around the sparse, bare-brick interior, while the church ceiling is transformed into a kaleidoscope universe of colours and shapes that, just like the music, ebbs and flows and transforms. Tonight, he’s accompanied by a drummer, who is also incognito; he wears a similar mask, and has a black hoodie pulled tight around his face. He plays mostly older songs and a few new ones, and addresses the audience in character throughout. “Thank you, dear Oslo. You’re doing the right thing,” he solemnly intones during a break.

Watching him work is spellbinding; from delicate passages to roaring crescendos, he knows exactly when to let loose and when to rein it all in, frequently going from a storm to a gentle breeze in the blink of an eye. At times, the drums are so soft as to be almost imperceptible, but they are there, quietly bustling along, adding depth and an anchor around which Lambert can dance. It’s a show to stir the soul and inspire the mind, and a mesmeric 45 minutes; prolonged applause at the end ensures his return for an encore.

Many performers have adopted alter egos through the use of a mask, most famously Daft Punk, but not all are as determined as the French duo to preserve their anonymity. For Lambert, the idea came to him when he started thinking seriously about what he wanted to do with the music he was writing. “For a long time before I wrote those first songs, I hadn’t played the piano and thought: ‘I cannot do anything with this, nobody wants instrumental music’. It just wasn’t working. I came back to it because I had a nice piano at home, and I found out that when you put felt in between hammers and strings, it actually sounds quite good and just like that, I started to write songs again. But I couldn’t imagine having to present myself; like, what would an audience expect a true artist to look like? One who was very emotionally involved with his music?”

“I wanted to have the freedom to be someone else, and it interested me, when going on stage, to be honest about the fact that this is a role I play because actually, that’s what everyone does. Even though they sometimes think they’re ‘authentic artists’, everyone is thinking: ‘How do I present myself on stage?’ That’s already a kind of a masquerade because it’s always only a very little part of you. Nobody will ever meet the guy on stage that brushes his teeth in the morning.”

It’s an interesting idea I say, trying to disconnect the art from the artist, and the artist from the everyday person. He says this distance helps him “focus on the music much better” and feel less self-conscious. “I don’t have to think of the presentation so much because it’s very clear; I don’t have to represent myself. Also, the distance between the person that makes music and me helps takes the pressure off. For example, Lambert can make mistakes that I probably wouldn’t forgive myself for. I can just say: ‘This Lambert is doing a lot of shit’ and at the end of the day, I don’t have to care so much. It makes things a lot easier for me.”

Creating a character is one thing, and it’s an admirable stand in our celebrity-obsessed age to place the art front and centre. But inevitably, as he becomes more successful, people will get curious. Isn’t he worried about a growing determination to discover the man behind the mask? “Well, if you don’t make good music then people lose interest in you, whether you have a mask or not. And while there are always some people that want to get to know the guy [behind the mask], I think they also know that deep down, it’s really not that interesting.”

He says he’s trying to find a happy medium on stage between Lambert and the real him, and that by talking between songs “they have a chance to get to know me, but in a way that I can control, which I like.” We talk about the point he made earlier, regarding mistakes, and how much artistic freedom such disassociation allows him. As himself, he would “reflect too much and that would disturb me.” All the better then to allow Lambert free reign when it comes to risks.

“I don’t have to think too much about what Lambert does because he’s following his instincts; he can take more risks, and try more things. I have the feeling I can challenge the audience more as well, and it’s easier for me to think about how they see the guy that I can create and form the way I want to.”

Inevitably, the rumour mill has already swung into action; a few days before we meet, some friends casually ask if it’s true that Lambert really is Nils Frahm in disguise. Chilly Gonazales is another name that’s bandied about, but given the eccentric Canadian’s distinctive hair and confrontational size, how anyone could confuse him with the slight individual hunched over his piano is beyond me. He finds such conspiracy theories “really strange”, and doesn’t understand why people think artists would do such a thing.

“It amuses me when people think I’m Nils Frahm or whoever; it’s funny. But I don’t know why people don’t wonder: ‘Why would Nils do this?’ I mean, if he did, he’d maybe play rock, or do rap, and not want to be connected to what he did before. Then I could understand someone wearing a mask. So it doesn’t make sense to me, but it’s a nice story, and that’s why people make them up; because it’s nice to tell a story. I can understand that, and I can relate to that.”

Identity speculation aside, the future looks bright. He’s settled into a writing groove and is happy with where his work is taking him; even better is the relative youth of his audience, and how he’s been able to bridge the gap between the formal world of classical composition and a more alternative crowd. He also doesn’t feel the need to push the envelope in terms of innovation to keep people interested in Lambert or push the project forward; not for him avant garde experimentation or electronic frippery.

For him, “a good tune is a good tune, even if you play it on a Casio keyboard”, nor does he want to be restricted by any kind of dogma or dependent on extra equipment. Sat in front of 88 keys is where he’s most comfortable, and so far, he’s yet to get bored. “I like the piano because I can rely on it, and I have the feeling I can always do a simple tune and do some production around it. Just me, the piano, and a tune; why would I need anything else?”

Backstage after the show, there’s a short interview to be done for Virgin Radio before his small crew packs up the last of their stuff and we head out for drinks. We find a quiet terrace bar beside the Akerselva River and settle in. Joking around and drinking beer, he looks like any other twenty-something enjoying some midweek revellery and wears the contented grin of a man hitting his stride.

“I don’t know if I will stay Lambert forever but for the moment it’s good. I’m so happy that it worked and of course, if I can play around the world and people come to my shows, I don’t really need much more in life.”

Sweet Apocalypse is out now via Mercury KX. For more information, including upcoming tour dates, please visit his official website.

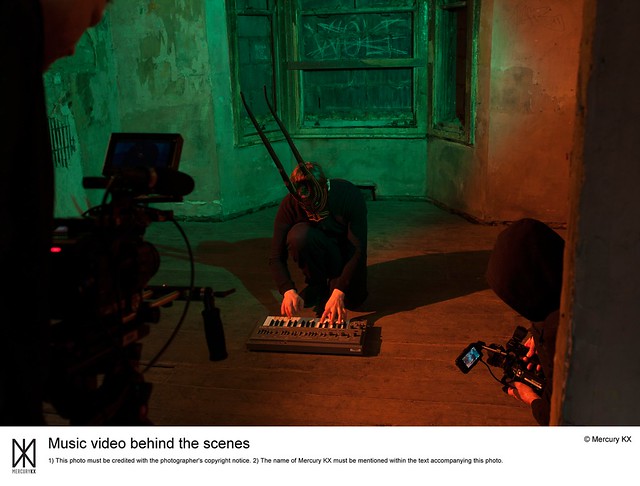

Photo Credit Mercury KX Showcase: Tabatha Fireman

Photo Credit Banner: Andreas Hornoff