"I don’t believe in an interventionist God." Is there a bigger way to ante up an album than this opening line, the one Nick Cave uses on The Boatman’s Call? It’s the kind of opening line we would have had a field day with in my creative writing workshops. Like, what does the speaker believe in? What does the speaker’s disbelief have to do with the story we’re about to hear?

The answer to that question is: pretty much everything. The love songs that comprise the album come not from mere skepticism but a hardened cynicism about the world. I mean, who puts a slow piano ballad titled ‘People Ain’t No Good’ on their most romantic album? Nick Cave does, perhaps because Nick Cave believes in counterpoint. He tells us as much in the Iain Forsyth-directed documentary 20,000 Days on Earth: “It’s really what my writing has increasingly become about, really, is counterpoint, and what one line can do to another line,” Cave says. "You write one line and then you put another line against it and you see what happens. And very often a kind of violent juxtaposition between two images that just don’t belong together can create a lot of tension, and be quite pleasing, you know.”

This kind of violent juxtaposition exists in spades on The Boatman’s Call. The hardness of the world often meets the speaker’s desire to shelter a loved one. Take these lines from ‘Lime Tree Arbor’.

“There will always be suffering / It flows through life like water / I put my hand over hers / Down in the lime tree arbour.”

The omnipresence of suffering is here, even among the intoxicating scent of lime trees this song always evokes for me. There’s no hint of a promise that their love will make the world right. There’s no promise of anything except not being alone in that moment in the lime tree arbor.

For years I’ve loved The Boatman’s Call. At first, I loved it aesthetically, conceptually, somewhat abstractly. I had been in love before, but not the kind of love Cave documents here. That didn’t happen for me until 2008. I’d been living in Boston for a few months, and the city and I had already developed a mutual distaste. People there seemed so hostile and skeptical, and I wondered when I would have a real conversation again. I tried to be hopeful, friendly, and optimistic, but every day the city crushed that in me. I have no idea how, in that scenario, I managed to fall in love.

I met my love through music, and we lived in our own soundtrack. Boston was still determined to take me down, but now I had an ally. Someone who would notice if I disappeared – at that point, even that seemed too good to be true. I’d meet him all city-bruised and jaded and he’d take my hand and we’d wander and talk about the music he was making and the things that I was writing. One night we got on a very crowded late bus. Trying to conserve space, we squeezed tight together. I wasn’t alone.

When we were really starting to get close, I played The Boatman’s Call for him. I wanted to share the beautiful love songs with him, but I hadn’t yet realized that I was finally living them.

We broke up for stupid reasons that masked a lot of very good reasons. It was agonizing to lose him, but I had lost something else: it was too painful to listen to The Boatman’s Call. I tried a few times, but it was too overwhelming. (I still can’t listen to Joni Mitchell’s Hejira for similar reasons.) Eventually, the stain of loss wore off and I was able to listen again. I heard how, woven into the songs, was not just this beautiful sheltering love but the omnipresent fear of losing it.

"O we will know, won’t we? / The stars will explode in the sky / O but they don’t, do they? / Stars have their moment and then they die”: - '(Are You) The One That I’ve Been Waiting For?'

“There's a lot about love disintegrating on this album because of the need to believe that love is something that can rescue you, and in fact, it doesn't at all. I mean love – romantic love – is a kind of distraction in the end," says Cave in a 1997 interview. Love doesn’t rescue you, there is no interventionist God who’s going to do a damn thing for you, and yet you have to live in this world. How do you have love without an interventionist God? How can you strip away fantasy and live in the real, awful, ain’t-no-good world and still proclaim that your lover’s black hair is charged with life itself?

Counterpoint. It lives not just in these songs but in Cave’s canon as a whole. He wrote the songs on The Boatman’s Call at the same time he was writing Murder Ballads, which was released the previous year. Murder Ballads is an album full of personas and songs with narratives, not to mention all of the, well, murder. But all the while Cave was singing lines like “Suck my dick because if you don't / You're gonna be dead” (from ‘Stagger Lee’), he was writing The Boatman’s Call. The music is far more stripped down than usual, as are the arrangements. But Cave stripped away something much bigger: his persona. He talks often about writing through a persona, a filter, but in these songs, we follow Nick Cave’s real triumphs and struggles in love. Some of these were even going on during the writing process; Cave wrote ‘Far From Me’ for a relationship that was just beginning, but it crumbled before the album was finished.

“You were my mad little lover / In a world where everybody fucks everybody else over”

Cave’s own love life has definitely been scrutinized in the context of The Boatman’s Call. Cave had been involved with PJ Harvey and admitted in a 1997 Mojo interview that a few songs on the album are about her. In the same interview, Cave says that ‘Green Eyes’ is about Tori Amos rubbing sparkles into her pubic hair, which he claims to have firsthand knowledge of. That claim intrigues because there has never been evidence or even rumors of the two being involved in any capacity. I once asked Amos if the song was about her (I did not mention her pubic hair) and she said she’d didn’t know, that she’d only briefly crossed paths with Cave while touring.

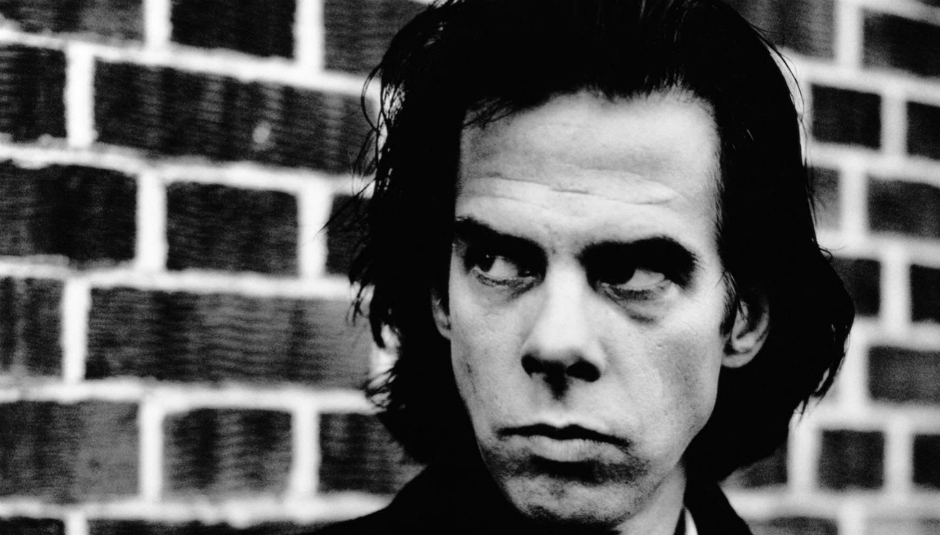

Whisperings of Harvey and Amos add a dimension of celebrity gossip, but it’s the lack of celebrity that makes The Boatman’s Call so hard-hitting. It’s the first time we’ve seen Nick the Stripper actually strip down, taking off his sybaritic dark prince garb and showing us the romantic spirit that has probably enabled his longtime cynicism in the first place.

Given all the larger-than-life violence of Murder Ballads, hindsight makes it easy to see why The Boatman’s Call was not only possible but also necessary and inevitable. Does anything change when we look past The Boatman’s Call? The next album Nick Cave released, No More Shall We Part, was released in 2001, four years being a long time between albums for the prolific Cave. In that time, he’d sought treatment for heroin and alcohol addiction.

When he returned to the studio, newly sober and newly remarried (to his current wife Susie Cave), it was natural that people expected to find Cave – always a fan of the Old Testament – to be hinting at themes of redemption now. But the album opens with ‘As I Sat Sadly By Her Side’, in which Cave and his lover take turns petting a kitten and then watch a man get trampled outside. She tells him that God doesn’t care about our benevolence or lack thereof; so there’s still no interventionist god, people still ain’t no good, and a woman’s hair is still the object of fascination. Maybe nothing’s changed since The Boatman’s Call, or maybe The Boatman’s Call changed everything, or maybe we should embrace The Boatman’s Call as a gorgeous document penned by a Cave who wasn’t so much changing as he was finally revealing himself.