By 1998, Blur had unwittingly painted themselves into a corner. Previous album Blur had been an unprecedented success, with the wholesale rejection of the pop stylings that had previously defined the band proving a worthy gamble. Singles ‘Beetlebum’, ‘M.O.R’, and ‘On Your Own’ saw Damon Albarn and Graham Coxon introduce a winning misanthropy to their formerly chipper (albeit barbed) songwriting. Furthermore, ‘Song 2’, their frantic homage to grunge, finally provided them with a long-sought-after transatlantic hit. The album’s embrace of the sort of effects-driven cacophony usually associated with Dinosaur Jr., Pixies, and Sonic Youth also won them many new admirers from an indie crowd more used to seeing them larking around on haybales (as in the ‘Country House’ video). Naturally, the heavier sound also pushed Coxon’s guitar to the fore – his distinctive, fractured lines were memorable additions to ‘Death Of A Party’ and ‘You’re So Great’ in particular – and Blur was such a complete statement that topping it was always going to be difficult, if not impossible. Yet, even against of backdrop of extreme emotional conflict, they almost – almost – pulled it off.

Crafting 13 (named, simply, after the studio Blur recorded in) was a challenge made even harder by the now-tempestuous relations within the group. At this point, it was becoming obvious that Blur’s universe was expanding in different directions, with Albarn favouring dense experimentalism over Coxon’s punk attack. Looking to freshen things up, Albarn recruited producer William Orbit, who had provided four tracks for that year’s remix album Bustin’ and Dronin’. Orbit must have wondered what he had got himself into, with members reportedly turning up to sessions drunk, abusive, or both – or simply skipping them altogether. It’s testament to his skills as an exceptional arranger of ideas that 13 looks anything like a cohesive body of work.

The breakdown of Albarn’s relationship with Elastica singer Justine Frischmann over the course of 1997 imbued much of his writing on 13 with a desperate sense of loss. That’s perhaps most evident on wrung-out penultimate number ‘No Distance Left to Run’, but it also informs the enthralling seven-minute opener ‘Tender’, with its London Community Gospel Choir-backed exhortation to “…get through it’. The song is a sort-of duet between Albarn and Coxon, but any initial suggestion of harmony conjured by that idea quickly disappears as the album unfolds. Indeed, ‘Tender’ might be as much of a lament for the breakdown of the bandmates’ relationship as it was for Albarn’s with Frischmann. Whatever the truth, it finds him returning to an often-explored theme: driving people away by loving them too much. His heartbreak is distilled to an almost unbearable potency on ‘1992’, with its simple, devastating refrain: “You’d love my bed / You took the other instead”. From there, the song succumbs to Coxon’s destructive will, swamped in a sea of static.

Coxon’s overarching influence is apparent everywhere on the first half of the album: the choppy, buzzing ‘Bugman’ – which could have easily crept on to Blur – ‘B.L.U.R.E.M.I’, which showcases the love for metal more often found on his solo records, and his masterpiece, ‘Coffee & TV’, perhaps 13’s most enduring statement, memorably starring that roving milk carton in its video. After that, however, Damon reasserts some control, with the lysergic twin peaks of ‘Battle’ and ‘Caramel’ representing his most out-there compositions to date. Brent DiCrescenzo got it right in his 9.1-scoring Pitchfork review: “Blur have finally found a sound to match their name.” Inevitably, these opaque sensibilities work best when they are tempered by Coxon’s contributions: one of the album’s most successful tracks, ‘Trimm Trabb’, is elevated halfway through by a truly fearsome guitar barrage. On tracks like this, when a balance between the two mindsets is briefly achieved, 13 truly flies. It was not an act the band would need to pull off for much longer.

Elsewhere, curios abound: re-listens reveal the surprising extent of 13’s feverish internal rhythms, with miniature hidden tracks bolted on to the side of several songs like dark, festering conservatories. ‘Caramel’ contains no less than two of these addendums – suggestive of a group almost outpaced by their own imaginations. Oddest of them all, perhaps, is album closer ‘Optigan 1’ – a relatively jaunty organ-led instrumental number which could be a cooler distant cousin to Parklife’s ‘Lot 105’. Like that song, it rather has the feel of end-credit music as it fades away into silence. In a way, it was: Coxon left Blur in 2001 during the recording of their next album, Think Tank, when tensions finally reached breaking point following a particularly fruitless session. That album’s desolate closing track, ‘Battery In Your Leg’, would be the final music to feature him for almost ten years.

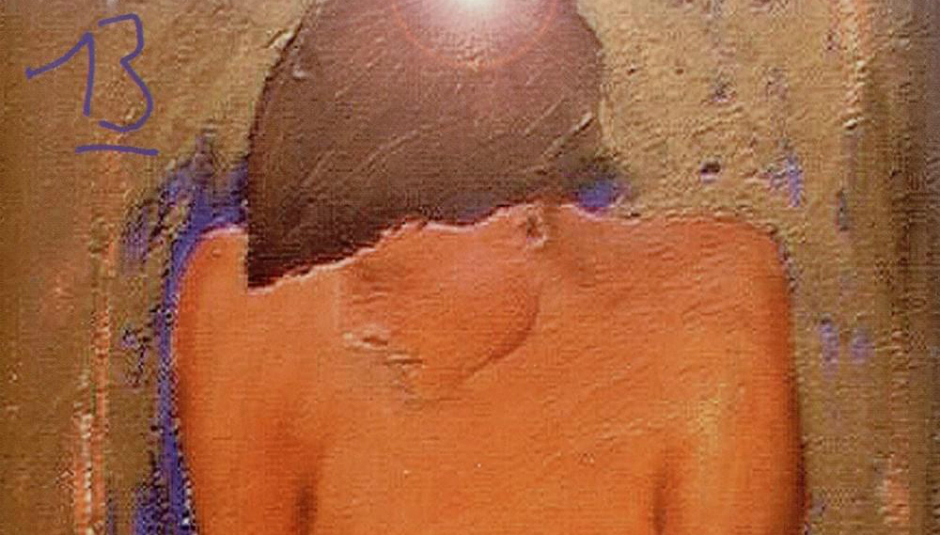

Messy, gangly, prone to unpredictable outbursts… 13 is the ultimate teenager. Like the figure depicted in Coxon’s cover art, it is awkward, high-shouldered and, yes, exquisitely tender. Yet as it turns 20, 13 shows itself to have aged remarkably well: it stands up today, not only as a dense, fraught bout of musical self-examination but as a classic in its own right. Even six albums in, Blur were still finding new colours on their riotously crowded palette.